Read the next installment: “Last Voyage“

It’s our first day at sea aboard the Maersk Seletar, a container ship. We’re about halfway between Busan, South Korea and Yangshan, China. Clear afternoon skies. Sunny. Hot. The sea is calm, almost as flat as a sheet of glass, when an alarm starts to sound. The Captain’s Liverpudlian voice comes clearly over the PA. “Abandon ship. Abandon ship.”

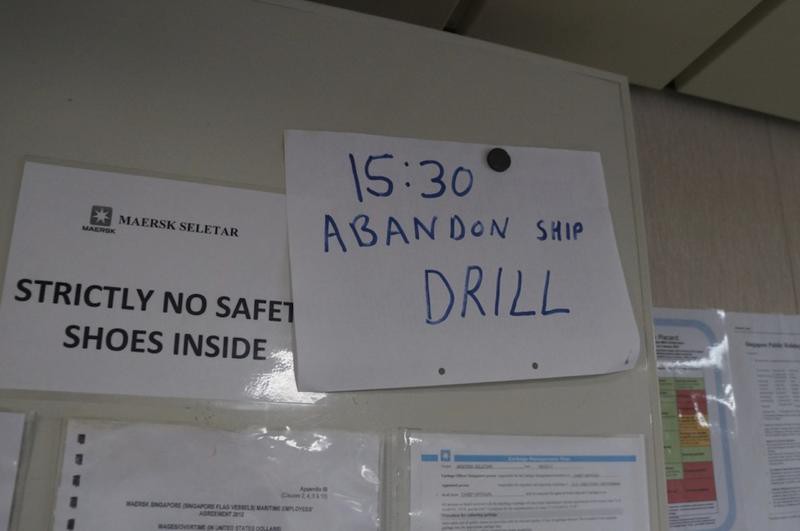

It’s a drill, one we’ve been warned about in advance. I know what I’m supposed to do. Head to my cabin, through the corridors liberally covered in workplace health and safety posters. Put on my safety boots, overalls, hard hat, and a lifejacket. Grab the immersion suit from the cupboard. Take the external stairs down to the port-side lifeboat, passing a cadet heading to the bridge to collect a SART (Search and Rescue Transponder).

But I’m not sure if I’m supposed to do a full “run for your life” dash to the lifeboat or a casual “oh gosh, is that the office fire alarm going off yet again?” stroll. I opt for somewhere in the middle–a fast walk. It’s the wrong choice. I’m the last person to the lifeboat.

I stand in line on the yellow circular number 12 marker. Everyone on the ship is assigned a number to stand on, along with one of two lifeboats to which we report and any duties to perform. As a passenger I only have to “assist as required.” The crew has to collect equipment and supplies like EPIRBs (Emergency Position-Indicating Radio Beacons), VHF radios (handheld portables able to access distress channels) and drinking water.

The EPIRB, VHF radio, and SART are for ensuring rescuers can find the lifeboat. My favorite is the SART, which emits x-band radar signals. These appear on a ship’s radar display as a distinctive series of 12 dots in a straight line.

We newcomers have to step forward and show we remember how to launch the lifeboat. Plug the bottom of the boat, disconnect the main power cable, remove locking pins, and other tasks I’ve since forgotten. Climb into the boat. Battery power on, gear in neutral, press the engine start button. Easy. Turn the engine off. Then try hand-crank-starting the engine, in case of battery problems. Less easy. Turns out my arms aren’t quite strong enough to hand-crank the engine.

It’s unlikely I’ll have to do this for real. I can’t imagine a possible situation where we’ll have to abandon ship and the 26 others aboard will be missing or unable to help. But we practice anyway, just in case the worst does happen. And also in case we encounter a Port State Control, a random, strict ship-safety check that can happen when arriving to a port. PSC has the power to impound a ship. We heard a story about one PSC that asked the bottom ranking crew to launch a lifeboat unaided.

The lifeboat doesn’t get lowered into the water during our drill, a process which can be dangerous. One crew member mentions that more people are injured in lifeboat drills than are saved by lifeboats.

None of our crew has had to abandon ship in a real situation. One mentioned a friend who had to jump the Maersk Miami after the engine room caught fire, the deck so hot that safety boots melted on the run to the lifeboat.

But this was an extreme case. If there’s an emergency, it’s usually much safer to stay aboard where there is equipment and shelter. Leaving the ship is a last resort. As our captain says, the ship is your best lifeboat.

Read the next installment: “Last Voyage“

Please note that this work is not available for republication under the terms of a Creative Commons license, as per most of our other content.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. Postcards From A Supply Chain follows Dan Williams as he traces consumer goods back through the global shipping system to their source. It was organized by the Unknown Fields Division, a group of architects, academics, and designers at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London.