Following the meteoric ascent of Asian economies, it’s no surprise that people are looking at other areas of the world for similar growth. In a world dominated by a massive division between the global rich and poor, where Western citizens find themselves frequently inundated with images of poverty and famine from the underdeveloped land beyond the equator, those with an eye for new markets, new opportunities, or even new narratives are looking out for the slightest sign of change. Has there ever been a time when so many fields–from the literary to the technological, the sociological to the economic–have found themselves so invested in the story coming out of the African continent?

This is a story that has undergone critique from various perspectives. Most of these critiques are trying to bring a more balanced view–focusing on what still needs to be improved–rather than further disparaging Africa’s all-too-easily-tarnished reputation. However, the initial optimism is not unfounded. Across the continent, there is an increased focus on enabling development from within, whether through educational initiatives or tech startups.

In some ways, this is a welcome counterweight to the increased economic presence of countries like China and their often problematic impact on local environments and economies. The debate around whether China’s interest in Africa is a welcome relief from Western faux aid or an example of neo-imperialism is one for another article. Certainly from one Afrofuturist perspective, there is nothing inherently celebratory about it. After all, racism does impact economic policies and there are still intensely retrograde attitudes toward black Africans among Chinese expats, though the cause of anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism did once result in pseudo-fraternity between Maoist China and newly independent African nations.

So, with the West established as an untrustworthy and exploitative partner, and the Asian tiger proving no better, the steady growth of educational incubators and centers from Tanzania to Liberia is reassuring; though it’s no indication that all of Africa’s problems are solved. After all, much of the internal political and economic infrastructure is riddled with corruption–however much it might be enabled by the interference of foreign governments. We tend to divorce the technological from the sociological, if only to make the analysis a bit easier, but this can be a problem if we’re trying to create sustainable technological development. Tackling development isn’t just a case of getting better at tech, it also requires a shift in understanding how we get better at tech and what kinds of tech we want to make.

This is one of the reasons I find the Meltwater Entrepreneurial School of Technology (MEST) in Accra, Ghana, so interesting. Founded in 2008 by a Norwegian, Jorn Lyseggen, its premise was “to help create role models that “¦ inspire the upcoming generation to become successful software entrepreneurs, creating wealth and jobs locally in Africa,” while providing the brightest graduates an opportunity to become world-class tech entrepreneurs able to compete with any of the offerings from Silicon Valley. In an interview, Lyseggen acknowledged that enabling entrepreneurs to truly understand their markets is a massive challenge, particularly when coupled with limited means to do so. In effect, for him the big question is how MEST alumni can be better service designers, as well as tech entrepreneurs.

This reminds me of how I sometimes describe user experience as “softcore anthropology,” where becoming one of the users under study is necessary to understand how they work and thus what they really need. This, of course, requires funding and availability even when working on a product for a small business–and much more so on a national and continental scale. That this is recognized as a real issue that needs tackling shows that for all my usual critique of foreign involvement in African development, there are some who do have a real understanding of what’s needed who aren’t looking simply to repeat the same structures in current “developed” countries.

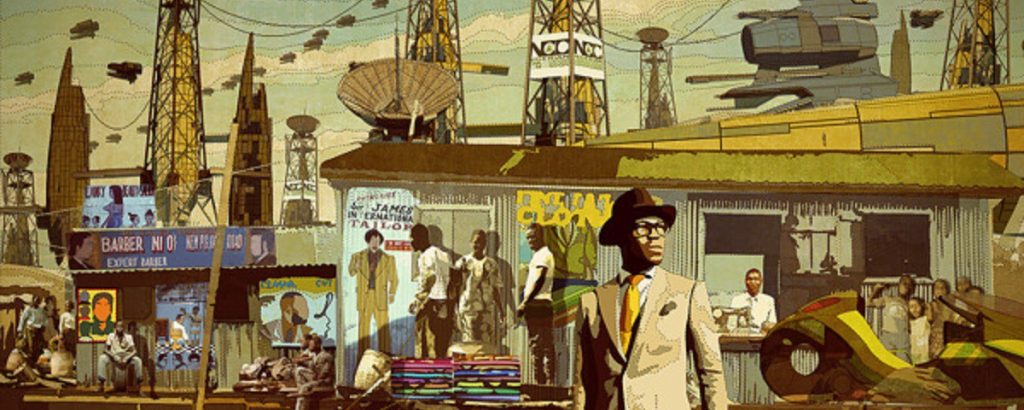

From the successful startups springing up thus far across the African continent, it’s fascinating to see the embodiment of what has, up until now, really been confined to the province of Afrofuturist theory. Businesses like Dropifi and RetailTower are unintentional examples of how differing philosophies of technology impact the kind of tech that gets made. Where in the West we still see tension between neo-Luddite and Transhumanist, such divisions don’t make as much sense in countries where technological development, whether for cultural or historical reasons, isn’t so easily tied to anti-humanism.

In much of Africa, technology is mostly associated with development since it equalizes the playing field between gender, ethnicities, race, and nationalities rather than supposedly destroying working-class jobs and making humans more dependent on terrifying AI. This intrinsically humanist view of technology is something you see in many African cultures throughout history–consider the Barongo ironworkers of Northwestern Tanzania where reproductive symbolism was used to describe metalworking tools and workspaces–and it’s interesting to speculate about subconscious connectives, linking the past to the present.

Another concern of Afrofuturism is how the speculative imagination is also a technology which needs to be embraced and developed by a society if it is to call itself advanced. In Ethiopia, tech hubs xHubAddis and iceaddis parallel the recent indie apocalyptic sci-fi film Crumbs; in Kenya we see a definitely African Afrocentrist movement inspiring filmic works like Pumzi, which sits alongside the success of centers like Nairobi-based *iHub; and in Ghana there’s the aforementioned MEST and Hub Accra, encouraging the growth of creative tech companies like Leti Arts, a games and comics publisher.

Here in the United Kingdom, I’ve joined initiatives like Ada’s List and Women Who Code that aim to tackle entrenched gender issues in tech. Although I have a vested interest in changing the common narrative associated with Africa, that doesn’t mean I’m blind to issues such as sexism and homophobia which also need to be addressed. From the experience of those of us “outsiders” in relatively liberal Western societies, it’s clear that true development must be intersectional. That’s why it’s heartening to see young women makers like HerHealth Uganda, AfriGirl Tech, Rasheed Yehuza, Clarisse Iribagiza and leading entrepreneurs like Anne Amuzu in the public eye, showing that some of the subtle biases we as Western women in tech experience are not only being dealt with, but perhaps have even been further eroded.

Conversely, the legal status of LGBTQI people in much of Africa is still under threat (we can discuss the reasons why over Twitter!) so it isn’t too surprising that we hardly see many out, queer techies speaking up about their contribution, but I sincerely hope this will change soon as a new generation of activists and social reformers focused on intersectionality take to the stage. Certainly those of us in the diaspora who are queer, black, and active within tech and social justice are always looking to the motherland to both raise the profile of and protect our fellow outsider technologists.

So, back to my initial question–are we seeing an Afrofuturist Africa being realized? Well, through various conversations and interviews, I’ve seen how we also need to challenge how we think about Afrofuturism in regards to Africa. Speaking with the fabulous Tabita Rezaire, I learned there’s a real frustration among her fellow artists with how the “Afrofuturist” label gets unthinkingly applied to their work, as though that’s all there is for contemporary African artists who engage with digital media. I’ve also seen this frustration elsewhere regarding the uncritical way the label gets applied to contemporary African art.

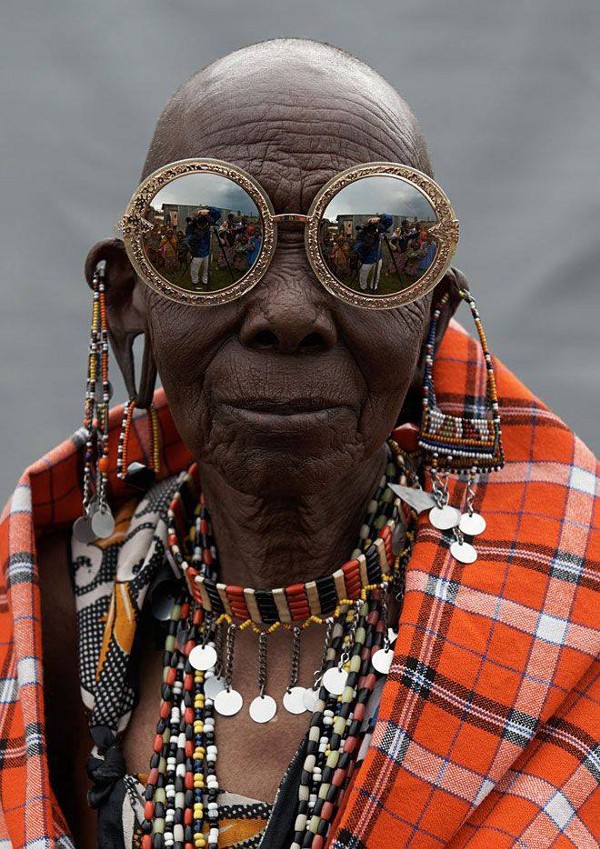

Is Afrofuturism even relevant considering how the post-colonial African experience of institutionalized racism might differ from that of the diasporic in America or Europe? Here questions arise about the dominance of Western black narratives, and the implicit racism behind how the label gets used. It’s led me to critique myself–why would we call the photo (left) of a Masai elder “Afrofuturist”? What does she call herself? What’s her movement? Is it that the Western imagination holds blackness and technology to be so incongruous that even we who know better still rely on the “single story,” even if it does originate in opposition to the usual stereotype? Or are we on the verge of rekindling a pan-African technological culture? Speaking to Emeka Okafor, founder of Maker Faire Africa, the questions I might ask about Afrofuturism and black involvement in STEM from a minority perspective are almost nonsensical. What does Afrofuturism even mean in contexts where to be black is actually to be the majority?

So maybe the inquiry itself is wrong footed. It’s not just new labels we need–we also need to think about who creates these labels. For now, let Africa, with her multitudes of languages, cultures, ethnicities, and faiths, speak for herself in her numerous voices.

I can only write about what I’ve seen. The innovation and verve of so many young people, the passion for learning and self-empowerment, and the tools now increasingly accessible are so powerful that I think in spite of many challenges–whether it be global and national exploitation, corruption, or bigotry–it’s safe to say we’re going to see some fascinating paradigm shifts. Will it be over the next decade or more? That’s hard to predict; certainly we should never think we can just relax and say “we’ve made it” (I mean, look at the 2008 recession if you want concrete reasons for why we should never take our eyes off the ball). True to the practical idealism inherent in much of post-colonial African thought and Western Afrofuturism, sometimes the goal is to keep evolving rather than to reach utopia.

Nonetheless, it remains evident that across cultures, ethnicities, genders, languages, religions, and countries, the dream of an inherently African futurism, where the potential of so many is utilized and fairly rewarded, has never been closer.

Further reading

- “Timbuktu Chronicles“

- “Uganda: Home of Health Innovations“

- “The Best Moments In African Sci-Fi 2015“

- “Why Ghana Started a Space Program“

- “Welcome to Nigeria’s First Robot School“

- “Five innovators who want to make your life easier“

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our collection of conversations about Afrofuturism, curated and edited by Florence Okoye of Afrofutures UK. Click the logo to read more.