I don’t know if it’s something to do with my own total absence of musical talent, but as both a music fan and journalist, lo-fi has always been my favorite of the fidelities.

As a teenager in the 1990s, I listened gleefully to scrappy pop-punk bands like Bis and Urusei Yatsura, who proudly displayed their DIY credentials in zines and on pin-badges, and in the songs themselves. For several years, my favorite member of my favorite band was Manic Street Preachers’ Richey Edwards, who could barely play (rhythm guitar) at all–it didn’t matter; he looked the part, he said the right things. Tracking back through punk history to its origins, I alighted on the infamous mantra of the late 1970s: “Here’s a chord. Here’s another. Here’s a third. Now form a band.” Anything more than that seemed like reckless self-indulgence–you can call it a false binary all you like, but creative passion and technical precision and finesse felt like a zero-sum game to me, and I’ve never quite been able to shake that.

It makes a certain kind of sense, then, that in the early 2000s, I would fall in love with grime and London’s pirate radio subcultures, write about them with religious fervor for a decade and a half, and finally publish a book on the subject. London’s unique, lickety-split digital version of rap was built by teenagers with little-to-no formal musical training, taking whatever cheap (or free, illegally “cracked” and downloaded) software they had to hand, creating strange, glowing, sci-fi sounds from whatever tools they could find.

Grime’s early-2000s pioneers like JME, Skepta, Wiley, and So Solid Crew broke the mold with none of the synths, samplers, and drum machines that had been vital to hip-hop production, instead doing much of their world-building on basic PC software like FruityLoops Studio. Inevitably, the sound was determined by the technology itself. One of grime’s only consistent formal attributes is that, like its sibling genre dubstep, it runs at around 140 beats per minute–the consistency is important for DJs to be able to mix records seamlessly. Producer Plastician is not the only one to have observed that FruityLoops‘ default tempo is set to 140bpm, which “may have a lot to answer for.”

Grime’s canon of cult classics is full of music made by producers who were unwilling or unable to do things “properly.” One of the genre’s most beloved instrumental productions, 2004’s “Functions on the Low” by XTC, took on a life of its own when, eleven years after its release, Stormzy used it as the instrumental for a freestyle in his local park, recorded just for YouTube. That freestyle, “Shut Up,” would go on to take the UK Christmas music charts by storm in 2015, and propel him to pop superstardom. But it’s “Functions on the Low” that is, if anything, more impressive in its cavalier DIY creativity. It took him half an hour to write, on FruityLoops, one morning before high school, while the rest of his family were still asleep. He used the computer keyboard in place of an actual keyboard, never got it mastered, rendered the audio file, burned it to CD, and took it straight to a vinyl pressing plant. And that was that.

For some, Fruity Loops on a cheap Dell PC was a lah-di-dah indulgence. An astonishing number of grime’s earliest classics–along with half of So Solid Crew’s 2001 hit debut album–were built on a “game” called Music 2000 for the PlayStation One, including Skepta’s first ever release, in 2002: “Pulse Eskimo.” Producers like JME and Smasher made their first tunes on Music 2000, recorded them to MiniDisc, and then had vinyl cut straight from the MiniDisc–without going anywhere near a recording studio. At this stage Skepta and his brother JME were even making beats using the game Mario Paint. Mixdowns are usually seen as a crucial stage of the recording process for even the most entry-level producer, where the elements are refined and balanced out to create a clean and coherent whole–but with grime, they sometimes didn’t happen at all before the tunes were released, such was the punk-like urgency to get them out there.

Influential grime DJ Logan Sama, for one, was happy with the devil-may-care approach to technical proficiency. “I don’t give a shit if a record is mastered well or not,” Sama said to me back in 2006, then a new graduate from the pirate-radio scene to the legit world (and new sofas) of London hip-hop/R&B radio station Kiss FM. “All I care about is the reaction it gets when I play it in a club. How technically well-made art is doesn’t matter: it’s art. Why would you want to analyze it on its technical merits? It’s not an exam. My white label [promotional vinyl pressing] of “‘Pulse X‘ still has the hiss from the AV-out cables from the Playstation they took it off to record it onto CD, when they took it to master it. You can hear it! The “‘bawm‘s are all distorted. That record sold over 10,000 copies!”

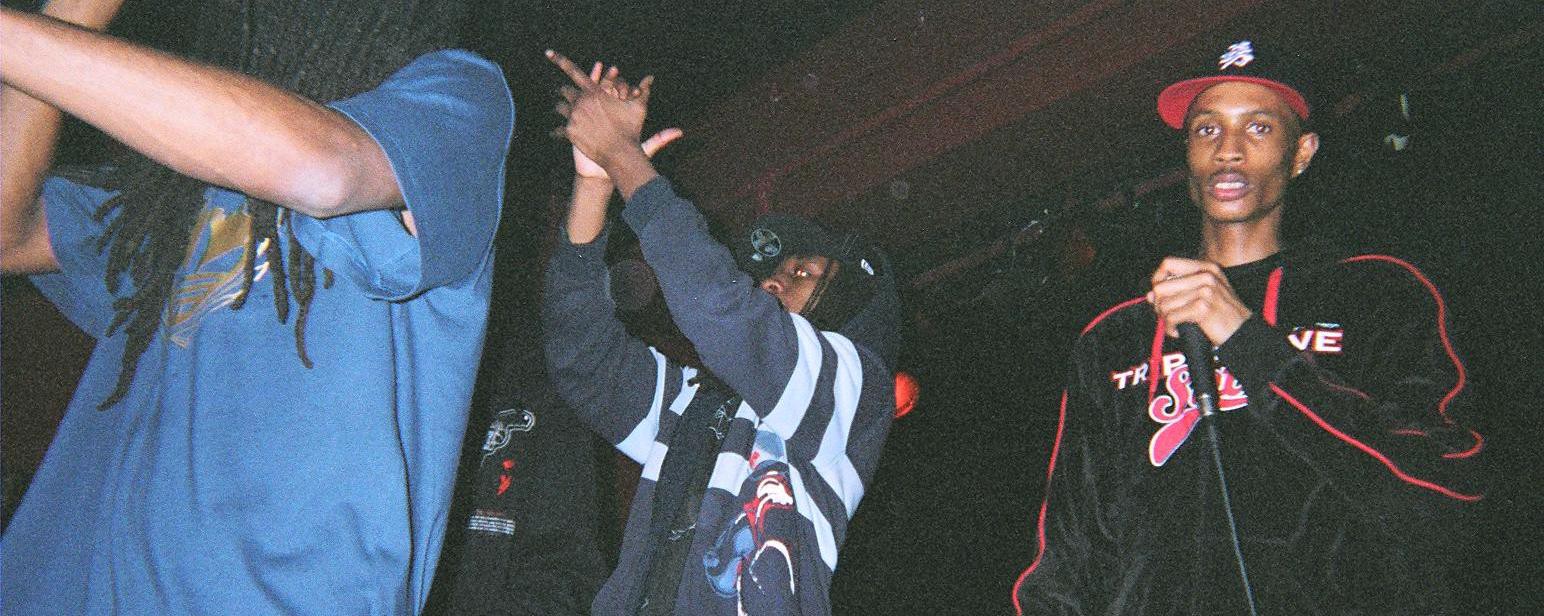

The vocal half of grime’s pairing of “beats and bars” was similarly developed with the barest minimum of technology. Most of the UK’s chart-conquering MCs learned and honed their rapping (or “spitting”) skills gathered around a tinny mp3 playing on a mobile phone in the school playground, on their housing estate, or in the street. Easy access and usability would always trump technological sophistication. Influential producers like Dexplicit, who made the instrumental that would be used for Lethal Bizzle’s “Pow!”, a UK Top 10 hit in 2004, even began writing music on non-smart, pre-internet “brick” mobile phones. “When I was in secondary school, everyone used to get me to create ringtones of their favorite songs on the old Nokia 3310’s,” he laughed, when I interviewed him for a piece about “sodcasting,” the much-maligned mid-2000s phenomenon where people (usually young teenagers) would play music off their phones on public transit.

Grime’s “whatever works” attitude to technology evolved so quickly that, for the generation below its inventors, even the genre’s origin story–the static-shrouded energy of pirate radio broadcasts, DJs lugging around huge record bags–seems like ancient history. “I missed that era, I was way too young!” Stormzy told me. “I was MCing in the playground, spitting lyrics over mobile phones–Sony Ericsson, Walkmans, W810s, the Teardrop Nokia phones, all of that. Vital equipment!”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Arts & Culture section, which looks at innovations in human creativity. Click the logo to read more.