As this article is being written, six people are living in space. Two Americans, three Russians, and one Japanese.

The six are working together aboard the International Space Station (ISS)–almost literally enclosed in a bubble, distant from everything below on Earth, including the politics. Makes you a little envious, doesn’t it?

The International Space Station is a chimeric symbol of global optimism (and more cynically, financial pragmatism). Its birth was the result of combining two separate sets of plans by NASA and Roscosmos, its Russian counterpart. In the aftermath of the Cold War, agreements for cooperation in space were forged to express unity and peace. But time passes–and the political situation in 2016 looks very different than it did in 1991, or even at the turn of the millennium when the first parts of the ISS launched.

All over the world, nationalism is resurgent. Russia, under the leadership of Vladimir Putin, is once again asserting its power on the global stage, putting it in direct conflict with Western interests. In the United States, Donald Trump’s brand of isolationist nativism has put him just a handful of electoral-college votes away from the White House. In Europe, practically every country has a nationalist party of its own to worry about, and Britain has voted to leave the European Union.

Since the Ukraine crisis, there’s even been a persistent background hum of stories about Russia’s intent to pull out of the ISS project, including one report of a plan to literally separate the station in two–with Russia taking its half and using it to build an independent space station.

In short, it feels like we’re drifting further from the future we were promised by Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry. He saw space exploration as an expression of human optimism–that together humans can achieve incredible things.

But recent events make me incredibly pessimistic that Roddenberry’s vision could ever come to fruition. With the rise of nationalism around the world, is international cooperation in space doomed?

To my surprise, many of the experts I spoke to are surprisingly optimistic about an internationalist future in space–though perhaps not for the traditional utopian reasons you might expect.

I started by asking the European Space Agency if the Ukraine crisis had hurt relations with Russia. Spokesperson Franco Bonacina told me it wasn’t a problem–that astronauts continue to work in “good harmony and in true spirit of cooperation and friendship.” But he would say that, wouldn’t he? The real picture, surely, is slightly more complicated.

Karl Leib, an expert in the politics of space exploration and a contributor to the journal Astropolitics, isn’t too worried either. He thinks the continued functioning of the ISS, despite Russia’s recent posturing, is itself a good sign.

“The crisis in Ukraine shows how terrestrial politics can threaten space cooperation, but fortunately, the ISS partnership weathered that storm,” he told me, noting that so far Russian threats to cut off access to Soyuz haven’t yet materialized. Leib added: “I think that shows that governments are able to compartmentalize policies if they think it is in their interest.”

The alignment of interests is much broader than the ISS, too. Mariel Borowitz studies international cooperation on climate data, which is collected by satellites. She said there are political barriers to cooperation in her field–but the advantages are evident: “The value of data is in its use–the more widely you make data available, the greater the return the government gets on its investment,” she argued.

Another example of international cooperation is the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee–which counts 12 different space agencies as members. Given that low Earth orbit is increasingly crowded, debris is clearly an issue that impacts everyone–so cooperation, even among potential adversaries, is important.

Perhaps this incentive-driven pragmatism is a better model for understanding modern space politics than misty-eyed cosmopolitanism. When incentives align, states are more willing to work together. Even the ISS can be viewed this way, as there are clear political advantages for all involved to be perceived as team players.

But when viewed through this lens, it is also easy to imagine how the incentives motivating each participant could quickly fall out of alignment. Albert Chapman, a space policy scholar at Purdue University, described to me a scenario in which U.S.-Russia tensions could effectively doom the ISS project.

“It’s possible that if NASA’s [manned rocket] Orion program gets up and running, the U.S. might take a more assertive stance toward Russia on space issues,” he said–because then the United States wouldn’t be reliant on the Soyuz to get astronauts into space.

“This would be more likely if Trump becomes president,” he explained. “In addition, as part of its constitutional oversight and funding responsibilities, Congress could decide to require NASA to develop plans to produce alternatives to the ISS without Russian involvement if it thinks Putin and Russia are engaged in policies antagonistic to U.S. space interests.”

To take an even longer view, the continued rise of China and the role of space prestige in its national mythos is perhaps the biggest challenge to the existing, peaceful coexistence in space. In 2003, in an example of “self-sufficiency” as it ascends to superpower status, China became the third nation to blast an astronaut–or “taikonaut”–into orbit.

Space is only a small part of this story, of course–China is already becoming more assertive in terrestrial politics, making big investments in Africa and staking out its defense claims in the South China Sea. Could this point toward the future militarization of space? Will we look back on today as a golden era of peaceful cooperation, one replaced by a new Cold War?

Chapman thinks the militarization of space is inevitable: “If China and Russia decide to maintain permanent, manned presences in space, I believe they will eventually seek to hinder access to space by the U.S. and other democratic countries,” he said. This would, he believes, lock humanity in a tit-for-tat escalation, which would require the West to also build a sustained, permanent military presence in space–to act as a counterweight to Beijing and Moscow.

There is evidence that jockeying for position in militarized space is already happening. Patricia K. McCormick, who studies international cooperation in communications, noted that other states–including China–have already hampered attempts by the European Union to build a “Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities,” refusing to sign on out of worry that it could restrict future capabilities.

Counterintuitively, this might not be all bad. The act of militarization could force new forms of cooperation between states. James Clay Moltz, an expert on conflict and cooperation in space, made the point to me that militarization would create new norms and expectations about how space is managed. He suggested that it could actually improve the exchange of information among the United States and its allies–improving traffic management and space situational awareness.

Conceivably, new forms of cooperation could also emerge between potential adversaries in a militarized space.

On January 11, 2007, China launched a projectile that destroyed a weather satellite–the obvious implication being that the country was testing anti-satellite technology which could be used in armed conflict. As the satellite broke up, however, it scattered an estimated 150,000 fragments of space junk around the Earth–each of which pose a theoretical threat to the ISS and other satellites we have in orbit. Because space is currently ungoverned, there was nothing stopping the Chinese from doing what they did.

Greater militarization could prevent an incident like this in the future, and force future cooperation between, say, China and the United States as they establish the norms of militarized space. In terrestrial warfare, a perverse stability exists because long-established principles make it clear to all combatants the expectation of the other, mitigating the risks of conflict escalation. For example, the game-theory logic of Mutually Assured Destruction meant that both sides in the Cold War knew exactly how far they could push the other before tensions would escalate.

In the same way, when space is inevitably militarized, chances are that all of the actors will tacitly cooperate and establish rules and norms.

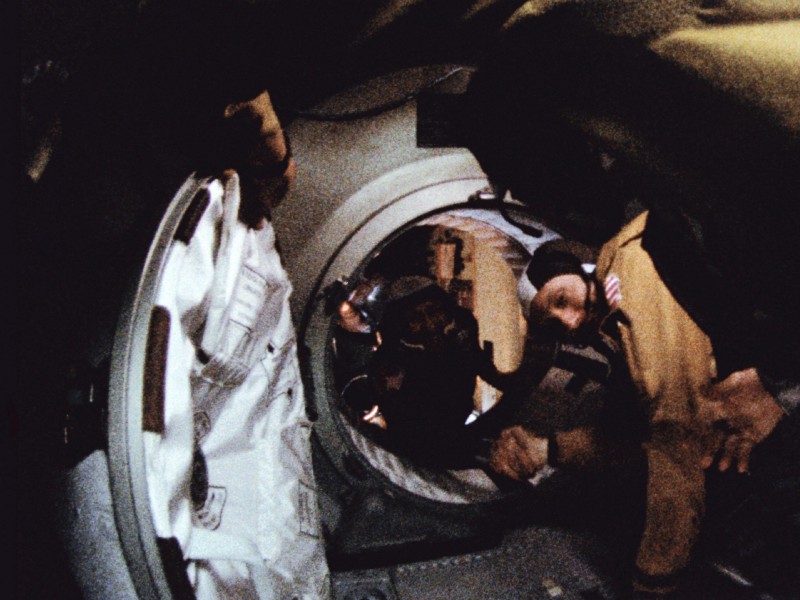

On July 17, 1975, American astronaut Thomas Stafford reached out and shook the hand of Russian cosmonaut Aleksei Leonov. Stafford and Leonov were onboard an American Apollo module that had docked to a Russian Soyuz rocket; this was the first-ever, in-orbit interaction between the two Cold War foes. It was a sign that the future of space exploration would be in the spirit of cooperation, rather than competition.

Things were, for a time, peaceful in space. But off-world life is unlikely to remain free of politics in the long run. New players like China, which have not been party to any of the existing norms of space conduct, are set to shake up the existing order–and could conceivably fire the starting gun on the militarization of space. In its own way, this could bring about a new kind of peace. The long-term future of space exploration might not all be handshakes in zero-G–but cooperation, however tacit, will have to continue.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Above & Beyond section, which looks at our understanding of the universe beyond Earth. Click the logo to read more.