In 2010, game designer and author Jane McGonigal gave a TED Talk. In it, she cited a statistic from a Carnegie Mellon University researcher showing that the average young person racks up 10,000 hours playing videogames by the age of 21–only slightly less than the time they spend in secondary education. Couple that with the fact that 1.2 billion people worldwide now play games, and you’ve got a huge audience willing to dedicate a hefty chunk of time to a medium often overlooked as a means for driving social change. Still, successfully tapping into that potential is another matter–especially when an entire generation suffers flashbacks to the educational games they were forced to play in school.

The dream of creating a videogame with a purpose beyond mere pleasure has existed since the dawn of Pong. Unfortunately, it’s really difficult to marry play with education and produce a genuinely enjoyable experience. Lean too heavily toward entertainment and you risk burying the subject you want to teach under a mountain of zombie corpses; go too far toward didactic lessons tacked onto a crappy gameplay mechanic and people will quite literally switch off. Get the balance right, though? Well, then you might just change the world.

One of the latest attempts to stimulate the mind as well as the thumbs is Eco, a global survival simulator. It presents you with a tricky challenge: Develop a civilization capable of tackling a meteor strike, drought, or rising sea levels, but don’t destroy the environment. While other games might cut you some slack on the realism front as you struggle to save the world, the trees you chop down in Eco don’t magically grow back. If you kill all the elks or wolves, they’re gone forever. And polluting the land with mining runoffs will poison your crops. In other words, this Minecraft-esque global survival game is just like real life, only blockier.

Although it’s still in the alpha stage, Eco has already garnered praise from tech and gaming luminaries. Bret Victor, the concept designer of the iPad user interface, said he’s “never seen a game concept so beautifully designed around systems thinking and evidence-backed decision-making.” Ken Karakotsios, the creator of SimLife, believes “Eco will help the next wave of decision-makers understand the impact of their choices on the environment, climate, and biosphere.” So are they right? And if so, could videogames help us address more than just environmental issues?

Aside from rare success stories like The Oregon Trail and the Carmen Sandiego series, many of the best educational games were never explicitly designed with the purpose of teaching. Take the Civilization titles: You can’t help but learn about history while you play them–it’s part of their DNA. Still, they’re primarily designed to be entertaining. Any knowledge you acquire about Roman military tactics or the Industrial Revolution is simply a side order to your banquet of fun.

A trawl through some of the serious and educational games released over the past decade shows many designers still haven’t grasped that fun is to videogames what plot is to novels (i.e., something you can’t do without if you want to reach a wide audience). Jen Helms, co-founder of Playmation Studios, believes the games industry could improve its attempts to take a playful approach to difficult problems. This led her to launch the Intentional Play Summit this year in California, a one-day event designed to encourage thought about how gameplay could be made more meaningful, or used to motivate and teach more effectively.

Many of the titles showcased in the summit’s arcade have a level of polish and craftsmanship worthy of commercial releases. We Are Chicago, for instance, aims to portray the harsh realities associated with growing up on Chicago’s South Side by putting the player in the shoes of a young African-American trying to look out for their friends and family. Then there’s Automata Empire, a cellular automata real-time strategy game inspired by Conway’s Game of Life, which Eurogamer described as “wonderful stuff.” As you play, you learn about the rapid growth caused by feedback loops and gain a greater understanding of global threats like climate change–a subject that videogames seem particularly well suited to address.

“With climate change, the changes are often far in the future, which can make it much easier for you to distance yourself from the consequences of policies and actions that take place today,” explains Helms. “A game can allow you to see those results more quickly, and therefore feel more urgency to act.”

Some games could even teach you sustainability concepts without you realizing it. As Shawna Kelly and Bonnie Nardi write in the introduction to their 2014 paper “Playing With Sustainability: Using Video Games to Simulate Futures of Scarcity“: “Many popular video games sustain compelling storylines that narrativize scarce resources, promote competitive and collaborative social interaction, and foreground survival goals–all necessary skills for making sense of a changed and changing global environment.”

Several visionary game designers have already made climate change the subject of their games. Chris Crawford is renowned for his conviction that games can teach complex subjects to a wide audience and bring about social change–a belief he poured into Balance of the Planet, a groundbreaking 1990 simulation game that tasked players with balancing the needs of growing industries against the earth’s ecology. The better-known SimEarth, created by Will Wright and published later the same year, took a different approach, giving players god-like control of the planet’s atmosphere, temperature, landmass, and other attributes (you can quite literally move mountains).

SimEarth was modeled on James Lovelock’s Gaia theory (he even assisted with the design and wrote an introduction for the manual), but like other climate change games such as Balance of the Planet, Oiligarchy, and 2011’s scientifically accurate Fate of the World, it doesn’t appear to have had a major impact on people’s attitude toward the environment–or at least not in the way Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle changed attitudes toward the meat-processing industry or Ken Loach’s Cathy Come Home fueled anger about homelessness in the 1960s.

That might be due to the genre’s somewhat heavy-handed approach to the subject–that is to say, too much focus on the data. Emily Treat, vice president of production services at Games for Change, advises climate change specialists interested in creating games to align themselves with a designer who can work with them on the creative element. “It’s also really valuable to get these games in front of people and do some testing, because if the games are made by the scientists studying complex issues, they might not know where to draw the line between complexity and how to simplify things,” she says.

Nevertheless, Foldit, a puzzle game in which players manipulate amino acids to figure out a protein’s structure, has demonstrated that games can be used to crowdsource complex science problems. Researchers analyze the highest-scoring solutions to determine whether they can be applied to relevant proteins in the real world and used to target diseases. Since its launch in 2009, more than 400,000 players–most of whom have no scientific background–have had the results of their work published in major scientific journals such as Nature, Science, and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Play to Cure: Genes in Space, a free mobile game, uses a similar approach to gamify the analysis of gigabytes of genetic data related to certain types of cancer. Developed in conjunction with Cancer Research UK, the game asks players to map a route through space and collect a fictional substance called Element Alpha. Finding the best route to pick up the most Element Alpha involves plotting a course through genuine DNA readouts; areas where Element Alpha is dense are areas where DNA may be copied or missing, and therefore faulty. In a little over a month, players managed to make 1.5 million classifications–a job that would have taken a scientist six months to complete by eye.

Sea Hero Quest is another example of what one might call a citizen science game. Players sail around the world in search of precious artifacts in the form of memories. The data they generate provides scientists with insights into people’s spatial navigation abilities, one of the first skills lost to dementia, and helps to establish the normal range of these skills. Once that’s been established, neuroscientists will be able to identify further guidelines for spotting dementia early, and help some of the 135 million people expected to suffer from the disease by 2050.

Videogames are often accused of trivializing war. But a growing number of titles focus more on the complex reality of conflict rather than gung-ho patriotism and flashbang thrills. Valiant Hearts: The Great War, for example, draws on letters and other historical documents to capture WWI’s pointless carnage. Meanwhile, This War of Mine puts you in charge of a group of civilian survivors in a fictional, war-torn city and tasks you with scavenging for supplies and crafting vital equipment from items found in the ruins. The game was inspired by the 1992″”96 Siege of Sarajevo during the Bosnian War, and developed with the help of the War Child charity. Released to critical acclaim, it reportedly turned a profit after just two days on sale, demonstrating that there’s an audience for games that treat war seriously. A set of downloadable artworks for the game, with profits going to the War Child nonprofit, also earned enough money to help 350 child refugees fleeing the conflict in Syria.

Both Valiant Hearts and This War of Mine wrap their message in enjoyable gameplay and polished visuals, but graphically simple games are just as capable of packing an emotional punch. The low-fi aesthetic of the award-winning Papers, Please, which casts you as a desk-bound immigration officer in a fictional communist country, only adds to the game’s Orwellian atmosphere. It’s up to you to check the documents of new arrivals at the border checkpoint and rubber-stamp their entry into mother Arstotzka; or if you suspect them of being a spy, smuggler, or terrorist, report them to the secret police. A wrong decision can have gut-wrenching repercussions for perfectly innocent people–if you fail in your duties, the country falls into a state of disarray and introduces even tighter security measures. Perhaps the game’s greatest achievement is that it makes you sympathize with both immigrants and immigration officers.

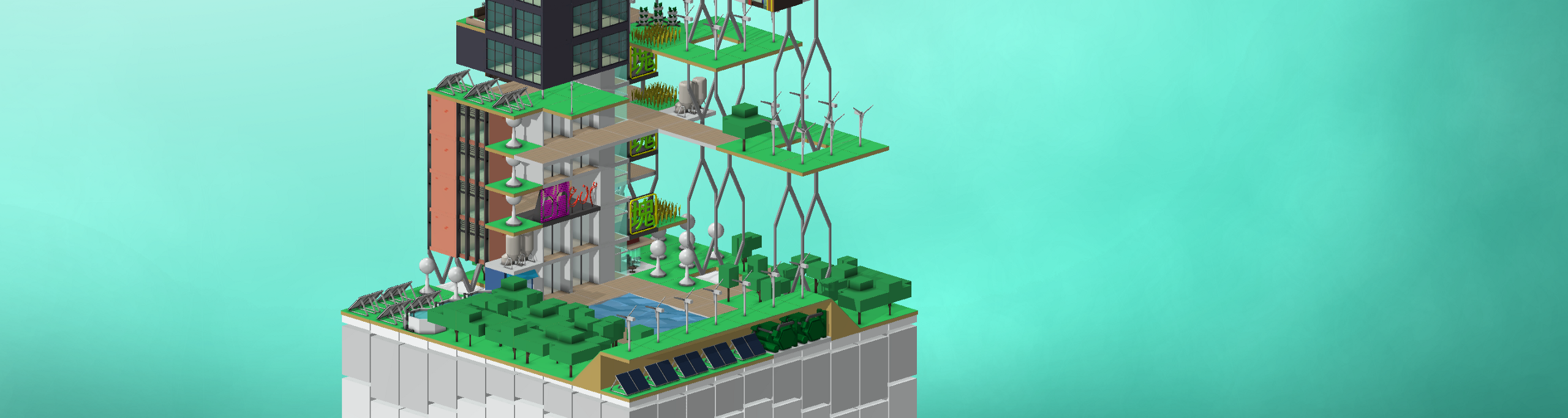

The rise of the indie scene that produced Papers, Please has created more opportunities for people with bold, quirky, or issue-based ideas to realize their vision. Today, a small team can develop a game on a minimal budget using the indie-friendly Unity engine and find an audience for its work on a range of platforms. Earlier this year, the Games for Change “G4C Climate Challenge” offered US$10,000 to the videogame designer who could create “a digital game that engages players to understand their role in addressing climate change.” The four finalists included the aforementioned Eco (which eventually won the contest), as well as Block’hood, a neighborhood-building simulator with an emphasis on ecology and entropy.

Block’hood reframes the city as an organism pumping inputs and outputs from one place to another like blood through a heart. Players can build an elaborate tower from urban farms, solar panels, windmills, apartments, and other elements from more than 90 different blocks, but must ensure these units don’t run out of resources or start to decay. Fail to provide trees with water, for instance, and they will stop producing fresh air.

Jose Sanchez, the architect, lecturer, and indie game developer behind Block’hood, says it was never his intention to try and accurately model a neighborhood or transport system’s CO2 emissions. Instead, he wanted to raise awareness about how our actions affect the wider world and contribute to climate change. “In a way, we took a very simple approach,” he says. “The player doesn’t have to be aware of all the terms or complexities of these issues, but they can really connect to this analogy of “‘I have a few trees and I need to provide water, and if the trees die the pollution starts going up.'” Sanchez hopes the game will help “raise a generation of much more aware kids, who make decisions with these ideas in mind when they become adults,” and is reaching out to city councils to develop Block’hood workshops and other initiatives.

Many of the global problems listed above burn slowly, and triple-A games usually prefer to draw their narrative energy from faster events–a nuclear war or pandemic disease, for example. Though, as games like Call of Duty: Black Ops 3 are beginning to embrace climate change themes, this might be changing. Even so, the subject still competes for our attention with a thousand other problems that feel more immediately pressing.

Which of them should we care about the most? What action should we take? The opinion pieces, e-petitions, and celebrity appeals that suffuse our online experiences often create empathy fatigue. Human beings generally resist being told we should care–we want to be shown why.

What better way to do that than with a game?

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our The Power of Play section, which looks at how fun and leisure can change the world. Click the logo to read more.