Four years ago, I stood outside a Burger King in Washington Heights with a 17-year-old kid named Eric Dorris. We were giving out overdose first-aid kits with naloxone, a drug that when sprayed up the nose of someone who has overdosed gives them the breath of life by knocking opioids from the body’s receptors. The public bathroom inside the fast food restaurant on the corner of New York City’s 181st Street and St. Nicholas Avenue–the intersection of old-fashioned heroin addiction and the latest trend in opioid abuse, prescription pain pills–was a well-known shooting gallery. The corner’s adjoining sidewalks were the best place in the Heights to buy anything from OxyContin to Vicodin. Back then, it was somewhere people would listen to our overdose evangelism. Some people we spoke to that day already knew about naloxone. They even carried their kit with a little note taped to it that read: “If you find me blue, spray this in my nose.”

Dorris was a lanky kid dressed in skinny jeans and a hoodie. While friends from his alternative high school in the West Village had elected to study things like glassblowing or origami, he had an interest in neurosurgery and was interning with the New York Harm Reduction Coalition. I was a fledgling journalist who had just learned about naloxone; Dorris was already planning to carry it to parties where his peers would crush up, snort, or otherwise ingest pills from their parents’ medicine cabinets to get high. He knew that opioid overdose is one liability that is near 100 percent preventable.

The little nasal device that could save lives on the spot was a telling symbol–its near anonymity at the time a potent reminder of America’s total lack of interest in helping drug users save their own lives. Developed in 1961 and approved by the FDA in 1971 to treat overdose, naloxone was virtually unknown to just about everyone in 2012, even doctors. It wasn’t stocked at pharmacies and was still a controlled substance in most states. It had a very sparse Wikipedia page, and no one cared much for offering it to back-alley junkies on a widespread basis. Drug users at risk of overdose, and their friends and families that worried about them, couldn’t really get it in the United States.

But as America’s overdose fatalities exceeded 47,000 annually in 2014, with opioids involved in some 29,000 of those deaths, wealthier suburban addicts transitioning from pain pills to cheaper heroin have by now reframed the country’s image of overdose. By all accounts, the traditional “war on drugs” has failed–the opioid overdose death rate more than quadrupling since the year 2000. It’s our kids, the friends of Eric Dorris, that have given addiction a new, sympathetic face.

Just as the epidemic is a key campaign issue in the 2016 presidential election, last week the American Medical Association clarified new opioid policies at its annual meeting in Chicago that encourage doctors to co-prescribe opioid painkillers with overdose reversal drugs like naloxone, proposing that insurers cover the “overdose antidote” with little or no cost-sharing.

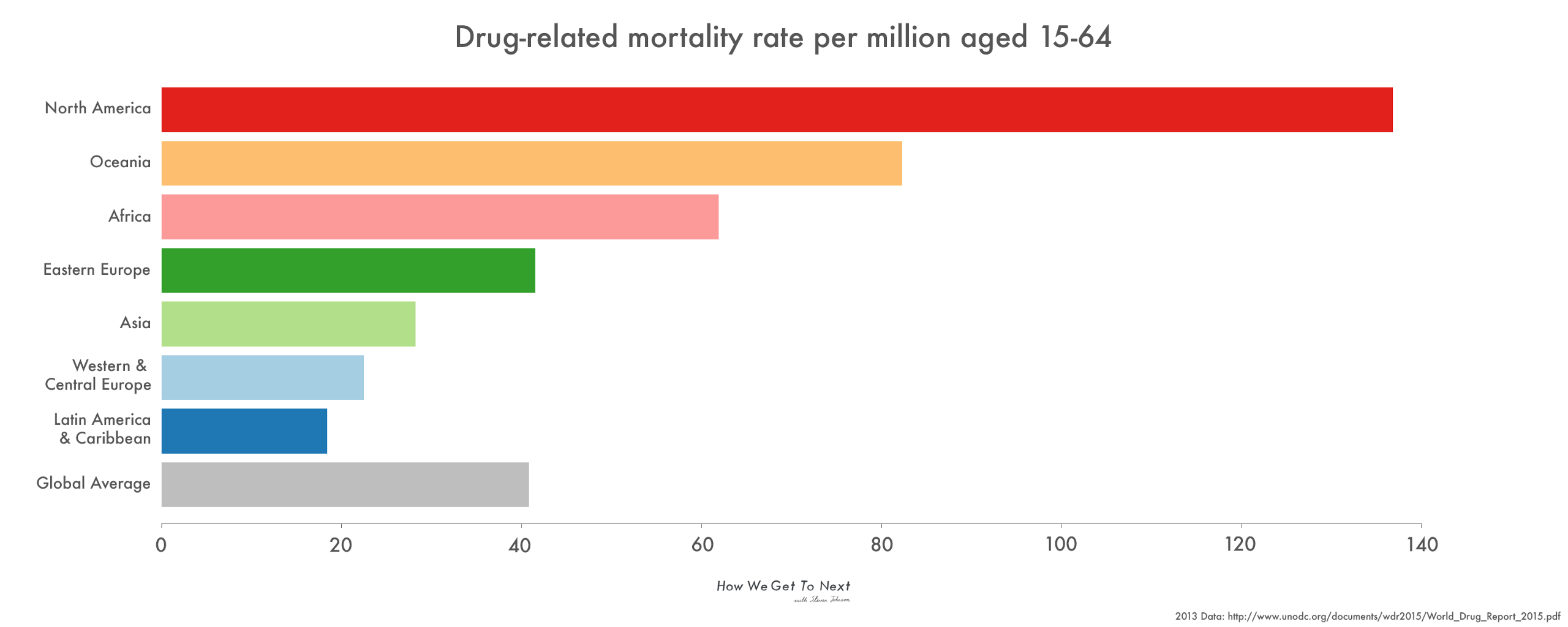

The tide has turned. Finally–finally–it seems the United States is ready to look toward a decades-old harm reduction movement that makes it safer to use drugs and first and foremost champions saving lives. Historically, that concept has been unpalatable to Americans, maybe even considered morally wrong. But as U.S. drug policy has failed to curb a climb toward one of the highest drug-related mortality rates worldwide at 4.6 times the global average, a softer way is in order. That means more access to naloxone, more clean-needle clinics to stop the spread of HIV and hepatitis C–essentially, safe spaces to use drugs–and a big win for grassroots advocates who came long before Eric Dorris and his generation, and have been laying this foundation for decades.

Colloquial narrative among drug-user advocates pins the roots of harm reduction in the United States to Chicago in 1990. Just after 7 p.m. on a Tuesday, 13 heroin addicts sat around a table over sweet rolls and coffee. Visually, they were a diverse group: men of different races and ethnicities. A handful of them were HIV positive. Each had been involved in 12-step recovery groups but, for one reason or another, found himself at this diner after feeling unwelcome or stigmatized. The goal was to deal with the meaning of the name they had chosen for themselves: The Chicago Recovery Alliance, one of the earliest harm reduction groups in the country.

It could have taken hours. That was until John Szyler, a heroin addict of 35 years who went on to overdose and die in 1996, opened with this: “Any positive change. That’s recovery.”

There was silence, until someone else echoed, “Shit, yeah, that’s it.”

Dan Bigg, who was 28 at the time, said: “And suddenly we were all in the same boat together.”

With a masters in psychology and one nasty case of distaste for the industrial addiction complex, Bigg was a self-described “happy drug user” back then. But by 1996, energized by Szyler’s death, he got serious. Losing his friend to a heroin overdose was enough reason to start thinking about what he could do to start saving lives. After researching pilot naloxone programs abroad in developing countries like Vietnam, India, and Thailand, with the help of a few doctor friends he was the first to bring it to the Chicago streets illegally. The Chicago Recovery Alliance debuted its community-based naloxone program in the spring of 1997.

“Are people willing to step back and say, “‘Our moralism is killing us?” Bigg asked me. “Do you make a reckoning that you are condemning groups of people to death based on behavior?”

Bigg faced opposition from the very beginning. “For the life of me I could not figure out why,” he said. “If you wanted to create something to test the fabric of society, to see if we would go forth and save someone’s life from accidental death [if we could], naloxone would be it.”

Even some of his harm reduction peers felt medical treatment for drug users should be left to emergency-room doctors and paramedics, who have been carrying naloxone for decades. Bigg distributed it anyway, driving around the city in a nondescript van of unpainted aluminum with a small blue and red arrow logo on its side. He even made house calls, reversing a number of lethal overdoses himself. After finding someone in a heavy nod, unresponsive to stimulation and blue in the lips from lack of oxygen, naloxone usually wakes a person who is overdosing in three to five minutes. “The person just starts to breathe like a baby,” he said. If administered within a 30- to 90-minute window, it’s enough to prevent death even if no additional care is provided. It has no side effects other than bringing someone with opioids in their system into immediate withdrawal.

By the year 2000, overdose deaths in Cook County, Illinois, had dropped 30 percent, said Bigg. This seemed to stall a 12-year increase in rising overdose rates in Chicago.

In 2001, as the United States saw a resurgence of heroin-based overdoses, a pilot program in San Francisco put some science behind what Bigg had started. After recruiting a small number of street addicts to monitor the safety of training injection drug-using partners to perform CPR and administer naloxone in the event of an overdose, researchers gathered data around 20 heroin overdoses during six months of follow-up. Study participants performed CPR 16 of those times, administered naloxone in 15 cases, and did one or the other in 19. All overdose victims survived. The point was: Addicts were willing and capable of helping each other.

Despite positive results, the movement had its critics–most notably the formidable drug czar under George W. Bush, Bertha Madras. After reviewing the research, she deemed it insufficient for enacting public policy and remained an adamant resistor of take-home naloxone programs. In a phone interview with me in 2012, she said harm reductionists had long ago nicknamed her “Dr. Death.” Even years later, she stood by her initial reaction. “For me, it really is callous to rescue a person from a near death experience and just leave them without professional intervention that can help them to recover and try to address the underlying issues that go with addiction,” she said.

By 1996, an army of harm reduction field workers and clinicians had initiated a host of community-based programs that offered naloxone to drug users, their families, and friends, reporting the distribution of over 50,000 kits (often illegally, as in many states it was still considered a controlled substance) and more than 10,000 death reversals by 2008.

This work, sometimes covert, paved the way for people like Dr. Alexander Walley, who after a chain of heroin overdoses in Quincy, Massachusetts, in 2010 helped expand the state’s naloxone program to equip the entire Quincy police force. It also inspired Bill Matthews, a former classical musician who once worked for the United Nations but by 2011 was spending his days trying to convince principals to let him into schools to speak about overdose prevention. (Now, in the Dansville Central School District in western New York, school nurses keep naloxone among the headache medicine they dispense.) It challenged the climate of abstinent-only recovery for those like health care professional Wanda Zanetti, who worked at a drug treatment center in New York State. There she promoted training around naloxone, saying that 80 percent of her patients opt-in to receive the kit–imagining they might one day use it on themselves or a friend.

It was all this that forced a 2012 FDA conference–over 4o years after the body had approved naloxone use–in which the federal government was finally ready to listen to a little street wisdom about overdose treatment. While there was good reason to look at taking naloxone over the counter as one avenue for containing a growing national overdose epidemic, getting it into drug users’ hands without a prescription would be tricky. At this time, it was only legally available with a prescription from special overdose prevention groups in 15 states and the District of Columbia under state Good Samaritan Laws that protected those who used it from criminal prosecution or civil liability when calling 911 after witnessing an overdose. Plus, naloxone had other complexities–it needs to be administered by someone else, so even if you had a prescription, the medication was likely not for you.

Madras still had oppositions; and FDA representative Andrea Leonard-Segal cautioned that the FDA does not control over-the-counter advertising. “You need to think about what a T.V. ad for naloxone might look like,” she said.

And yet, perhaps louder than the detractors rang the voice of Susan Gregory, whose son had died of an accidental overdose at age 20. “My son died alone on a bathroom floor,” she said. “On the other side of that door were a lot of people and a pharmacy. I didn’t know about naloxone then. Why didn’t I know about it?” she cried.

Four years later, now we do. To date, law enforcement departments in 36 states carry naloxone. CVS pharmacies now have the drug available over the counter in 23 states. As for the old guard monitoring the war on drugs in the White House, it’s gone. The current drug czar, Michael Botticelli, is the first director of national drug control policy to be in recovery from substance abuse himself. He was a keynote speaker at the 2014 Harm Reduction Conference in Baltimore, where he explicitly offered his support for both the movement and naloxone.

All this amounts to recognition of a true crisis–and a compassionate bending to a once-staunch ethos that judged those suffering from drug addiction and the actions we take to help them.

But here’s the thing: overdoses aren’t just a U.S. problem. Naloxone is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines, or those considered necessary within any basic health system, for good reason. While the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime World Drug Report 2015 confirms that North America contributes an estimated 23 percent to the number of drug-related deaths globally (which in 2013 was around 187,100), it also notes that this high figure is in part due to better monitoring and reporting around drug-related deaths in higher-income countries like the United States. In other countries, drug use and overdose data simply isn’t collected.

No country in Asia or Africa conducts household surveys on drug use like we do in America and Western Europe–it’s too expensive–and data collection around drug-related mortalities is very limited. Still, there are a raft of statistics showing that drugs are a global problem. The WHO estimates that 69,000 people die each year around the world from opioid overdose alone. The UNODC reports that in conjunction with the United States, the Russian Federation and China account for 48 percent of the total number of people who inject drugs globally. With 80 percent of the global opium production occurring in Afghanistan, injection drug use is also high in the nearby Middle East and North Africa. Meanwhile, overall rates of drug use in Oceania (Australia, New Zealand, and a number of Pacific Island countries) are well above the global average, prescription opioids being much more popular than heroin in the region.

In Italy, naloxone is available in pharmacies without a prescription, and as of 2011 Scotland became the first country in the world to implement a national take-home naloxone program. A UNODC and World Health Organization 2013 discussion paper about preventing and reducing opioid overdose mortality noted that community-based naloxone distribution programs exist, to some extent or another, in over a dozen countries, including Afghanistan, Australia, Canada, China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Thailand, the United Kingdom, Ukraine, and Vietnam. Many were in pilot or experimental form at the time and may have ceased operations, but others are likely to have sprung up, too.

Naloxone is currently available in hospitals in Kenya and Tanzania, but there is no access to overdose treatment for the wider population in Africa. Reminiscent of Bigg and his colleagues, though, there are boots on the ground: The national harm reduction network in Mauritius, together with the Kenyan AIDS NGOs Consortium (KANCO), used the “Support. Don’t Punish” campaign as a platform for people to talk publicly about drug policy reform.

Although harm reduction is becoming more accepted across Asia where there are an estimated 3.15 million IV drug-users, punitive drug policies are still in place. China has no national program for overdose prevention, though AIDS Care China did open naloxone peer-distribution programs in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces.

In Russia, it’s believed that around 90,000 people die from overdose every year. If that’s true, this accounts for half of all lethal drug overdoses worldwide. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the country–again, with opium-producer Afghanistan at its doorstep–has claimed the world’s highest rate of injection drug users with 1.8 million. The Russian Federation continues to implement a zero tolerance approach to narcotics and has used anti-propaganda laws to suppress harm reduction services and advocacy.

Halting a global epidemic around fatal overdoses won’t come without effort or cost. It certainly hasn’t in the United States, where on average 130 people still die from them every day. The road to changing policy has been a long one, and countries that follow a similar path of resistance might meet a similar fate. There is, of course, another way.

It’s a movement that found life on the streets over 25 years ago; it’s an old method for treating drug users passed down by forgotten heroin addicts of yesterday. It’s one that has gained an ally in a new generation of kids like Eric Dorris, who are facing the same threat of drug overdose–at worse scale. In the four years since he took up the torch and hit the streets (and high school parties) with naloxone, we’ve seen serious progress around overdose awareness and drug policy change in America.

To continue this trend will surely require more work, in the United States and globally. But if you’re in Dan Bigg’s camp–and that of advocates from so many pockets of the globe now voicing support for reducing harm for drug users–any positive change will do.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Vital Signs section, on the future of human health. Click the logo to read more.