With the stories of Alan Turing and Stephen Hawking both up for Oscars, here’s 10 more historical characters from the fields of science and engineering crying out for the Hollywood treatment.

1) Hedy Lamarr

It’s kind of puzzling that a film about Lamarr hasn’t been made already. Hers is a story of sex, war, and a bit of light engineering. Born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler, her early career in acting involved performing the first orgasm in a non-pornographic film. An unhappy marriage to armaments magnate Friedrich Mandl meant parties with Mussolini and Hitler–but at least taught her something about military technology. She escaped the marriage in 1937 and met Louis B. Mayer (the second “M” in MGM), who changed her name and brought her to Hollywood. During the war, she bumped into avant-garde composer George Antheil at a dinner party and they cooked up a plan to aid the U.S. Navy’s radio-guiding systems, which later helped build the technology we now call Wi-Fi.

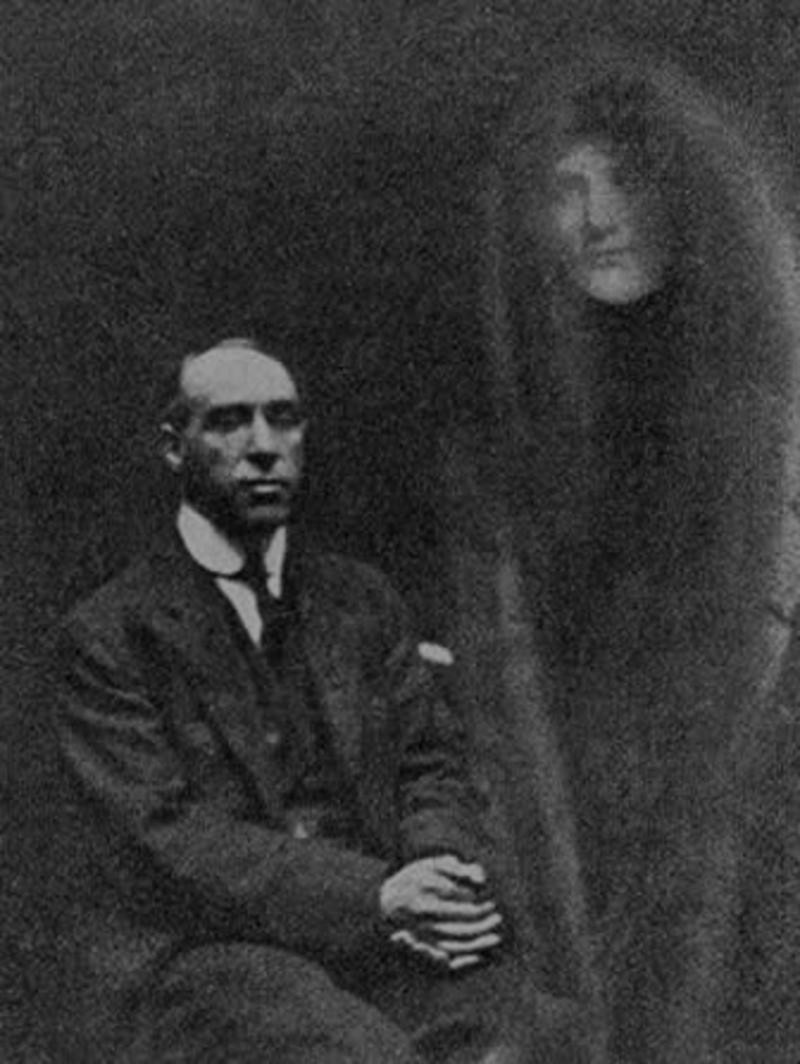

2) Harry Price

The original Ghostbuster, an interest in conjuring and magic tricks in the 1920s led Price, a native Londoner, to psychic research. He wanted to study this scientifically, debunking the many frauds while maintaining a belief that some mediums were real–unlike more straightforward skeptics like Houdini. Other researchers took him seriously, and in the 1930s the University of London offered him space to found a Council for Psychical Investigation. Not exactly a great scientist in the traditional vein, but certainly a story, if only for his collection of magical texts and fake ectoplasm. And there is a talking mongoose called Geoff.

3) Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim

Swiss physician, botanist, alchemist, astrologer, and alchemist of the 15th century, von Hohenheim was a keen reformer known for his arrogance–he’d publicly burn books to stand up to the medical authorities of the time. Traveling across Europe and Asia as an army doctor and occasional miner, he picked up knowledge from a wide range of people, writing that he wasn’t ashamed to learn from butchers, barbers, and tramps. He’s better known as Paracelus, which he coined himself, meaning equal to the Roman scientist Celsus. Told you he was arrogant.

4) Paul Erdős

A Jewish-Hungarian mathematician of the late 20th century, ErdÅ‘s was known for his eccentricity. TIME dubbed him “the Oddball’s Oddball.” Most of his family died in the Holocaust and he never married; he’d travel around the world never settling for long. He was known for turning up at colleagues’ doorsteps, announcing “my brain is open,” and staying only long enough to collaborate on a few papers before moving on.

5) Émilie du Châtelet

Born into a wealthy French family of the 18th century, she apparently appalled her mother by chatting with guests about astronomy rather than clothes or court gossip. Married off at 19–to a man of 34–after an affair with the man who inspired the character Valmont in Les Liaisons Dangereuses, she started a relationship with Voltaire. They set up a laboratory in her home and would both compete and collaborate on scientific work. They entered a 1738 Paris Academy prize on the nature of fire; though neither won, both essays were published, and she thus became the first woman to have a scientific paper make it to print through the Academy. In her early 40s she started an affair with a much younger poet, became pregnant and died not long after giving birth.

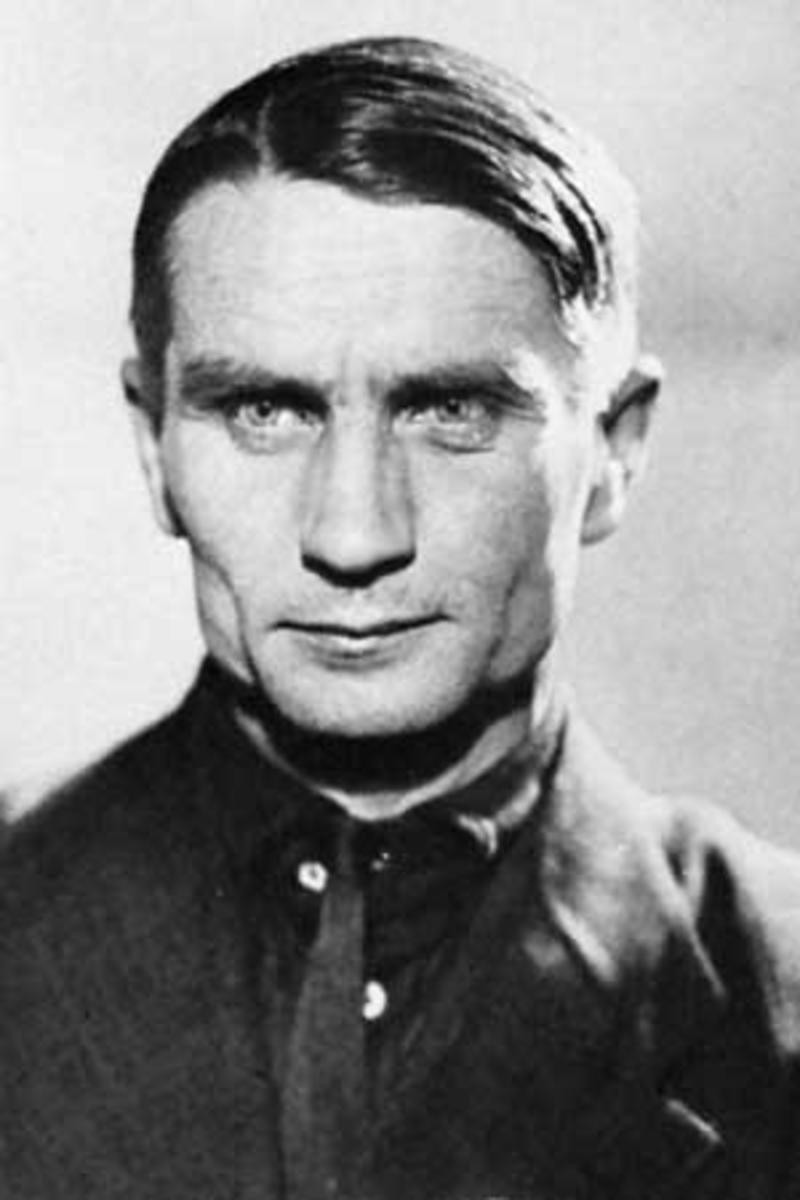

6) Trofim Lysenko

A scientific anti-hero, Lysenko is sometimes blamed for serious famines in the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Arguing for a uniquely communist science, unhampered by the bourgeois ideologies and hierarchies of the capitalist West, Lysenko rejected Mendelian genetics, favoring his own ideas of “vernalization.”

The idea of a true, collective science of the working man was appealing for many reasons. But sadly it was also wrong, and not exactly without blinkered hierarchies of its own, leading to suppression of much biology in the USSR and, because it was applied in agricultural policies, death.

7) Kodjo Afate Gnikou

In 2012, Togolese maker Kodjo Afate Gnikou produced the world’s first 3D printer made from e-waste. He’s currently working on a version for NASA, which he wants to take to Mars. Perhaps Hollywood should wait to see what he does next, but it’s already a great story.

8) Frank Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer might be infamous as the “Father of the Atomic Bomb,” but little brother Frank’s way more interesting. He followed his brother into physics and reportedly even stood by him at the first test. But, post-war, he was blackballed from universities due to his brief stint as a communist in the 1930s. (There was also a girl”¦)

So he packed up his lab, sold an old Picasso his father had left him, and bought a cattle ranch. He was happy there, but the local kids needed a science teacher so he was soon sucked back into physics. An inventive teacher, he’d start lessons with trips to the local dump to collect bits of old machines to use in demonstrations of thermodynamics. On one occasion, he even killed and dissected a kitten to demonstrate part of the ear. He returned to universities for a while, but, disillusioned by how corporate they’d become, he moved to museums and established the world-famous Exploratorium in San Francisco.

9) J. B. S. Haldane

From an aristocratic and secular Scottish family, Haldane worked with his father in their home laboratory starting from the age of eight. He published his first scientific paper at age 20, but his early career was interrupted by WWI, during which he served in France and Iraq.

He then took a research post in Oxford, before moving to Berkley and then back to London. Haldane emigrated to India in 1956, reportedly to enjoy the rest of his life not wearing socks, though it was probably more to do with his politics (plus his wife had been arrested for excessive drinking and refused to pay a fine). He was known for experimenting on himself, including an investigation with his father into the effects of poison gases.

10) Beatrice Shilling

Aeronautical engineer who played a key role during WWII by correcting defect Spitfire engines. The daughter of a butcher, her (female) boss encouraged her to earn a degree in electrical engineering at Manchester University.

In the 1930s, she raced motorcycles, often beating professional riders. After the war, she raced cars and reportedly refused to marry her husband until he also had been awarded the Brooklands Gold Star for lapping the circuit at over 100 mph.

Honorable mentions:

- Margaret Lovatt, NASA-funded research involving dolphin sex and LSD.

- Dorothy Hodgkin, pacifist, socialist chemist, taught Thatcher.

- Alexander Borodin, illegitimate son of a prince, chemist, composer, women’s rights activist, died dancing at a party.

- Joseph Bazalgette, plumbing, but really, really visionary plumbing. Ada Lovelace, sometimes known as the world’s first computer programmer, daughter of Byron.

- Fang Lizhi, Chinese astrophysicist and activist who inspired the pro-democracy student movement of the late 1980s.

- Mary Anning, self-educated, working-class woman who became one of the greatest fossil hunters of the 19th century.

- Richard Doll, established a link between cancer and smoking.

- Tycho Brahe, if only for the false nose and the amazing facial hair.

- Henry Wellcome, born in the Wild West, ended his life a Knight of the British Realm.

- Lise Meitner, infamously overlooked for the Nobel Prize, escaped Nazi Germany.

- Guy Callendar, amateur meteorologist, worked out the link between fossil fuels and climate change.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Arts & Culture section, which looks at innovations in human creativity. Click the logo to read more.