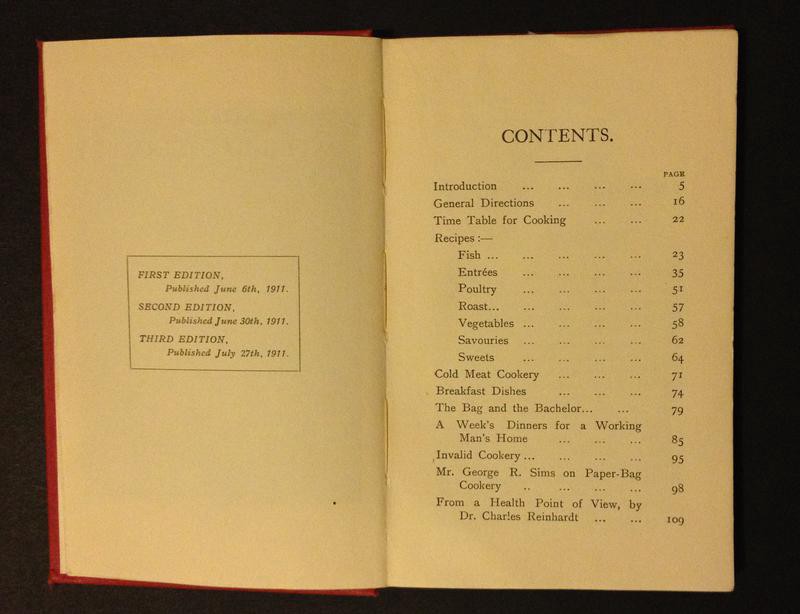

Nicolas Soyer’s book, Soyer’s Paper-Bag Cookery, enjoyed a brief flurry of popularity upon its publication in 1911, then fell out of print and into obscurity. This now-rare little gem demonstrates how you can cook practically any meal with just an oven, a metal rack, and paper bags (excluding soup, understandably). Its author believed his ideas would change the world.

And it’s hard not to be swayed by Soyer’s evangelical fervor that this cooking method would be a great democratizing force:

“Expert cooking, which has hitherto been the luxury of the RICH, can now be equally the privilege of the POOR. The method can be used with equal success in the cottage and the mansion.” [Soyer’s caps.]

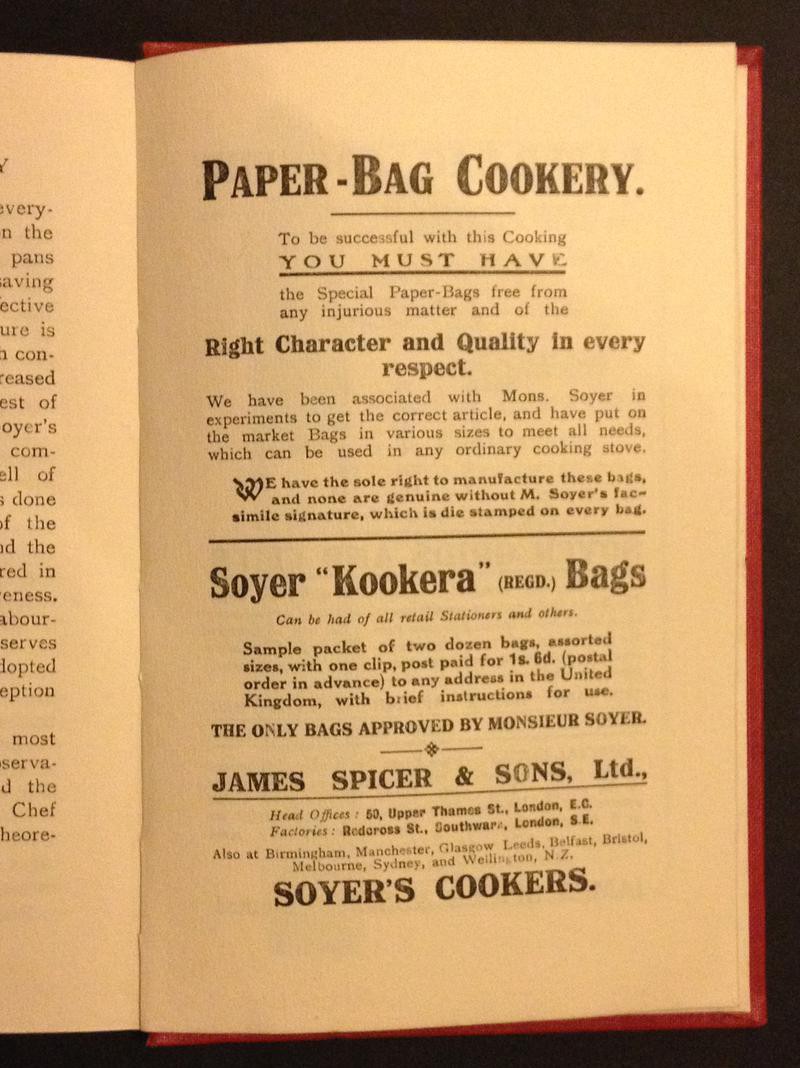

In his vision, the rapidly expanding middle classes would no longer have to scrape to afford kitchen staff if they simply combined foodstuffs in a paper bag. Paper-bag recipes required far shorter cookery times than normal, thus saving fuel, too. And women would be liberated: “There will be no pots or pans to clean; the drudgery of the kitchen will be abolished,” Soyer wrote. (This, of course, ignored the fact that to cook three meals a day chefs needed to buy at least 1,000 Soyer-brand paper bags every year.)

Soyer hoped his bags would be a boon for singletons: “Girls and women living alone in single rooms, typists, clerks, and school teachers would rather dine or sup on a bun and glass of milk than face the trouble after a weary day of cooking a meal and washing up afterwards,” the book proclaimed. Even men might be able to cook, too, using Soyer’s detailed instructions to an incompetent bachelor for throwing a four-course bag-cooked dinner party for a cantankerous, eminent lawyer.

Paper-bag cookery also promised to keep food succulent, digestible, and nutritious, in stark contrast to the usual Edwardian fare. Furthermore, at a time when home hygiene was hard-won, the disposable bags kept at bay the early 20th century menace of microbes, as well as the threat of lead poisoning from cooking vessels.

Truly, such a humble object as a paper bag promised a lot.

Soyer’s paper-bag revelation started with a bang–literally. Working as the private chef to the Dowager Duchess of Newcastle, he was preparing fish en papillote–fish wrapped in parchment, the original paper-bag cookery–when the kitchen maid added too much sauce, causing the package to explode in the oven.

Disaster? No. Soyer discovered that the fish was cooked to juicy perfection. Thrilled, he experimented with other recipes, soon learning to prevent explosions by placing the packages on a metal rack in the oven to allow air to circulate on all sides. The results all emerged exquisitely juicy, with one stubborn problem.

Everything tasted of paper.

For years, the indefatigable Soyer tried to eliminate the invasive papery flavor, but to no avail. Eventually, he admitted defeat and got on with his life; until one day, a full 15 years after his fish parcel had first exploded, he read in the newspaper that Herr Lampert, a chef in Frankfurt, was marketing a special oven with which to perfect paper-bag cookery. “All my old longing to excel in Paper-Bag Cookery reasserted itself, and I at once sent off a challenge to my German rival,” he said.

A paper-bag cookery duel ensued. Soyer swept to victory with 11 dishes, despite all 11 still smacking of paper.

Buoyed by victory, Soyer did what he should have at the beginning: He went to a stationer and asked him to supply paper which didn’t imbue food with the tang of wooden pulp. The man did. Thus, at long last, Soyer’s ambitions could be realized. He released his book, his Soyer-branded range of paper bags in six sizes, plus bag clips and oven racks, and waited for cookery and society to transform.

But, over a full century later, though we might pop a bag of popcorn in the microwave and sous vide is all the rage, saucepans remain in our kitchen cupboards and nobody speaks of Soyerizing their food. Where did Nicolas Soyer go wrong?

Perhaps his pet project was not glamorous enough. Perhaps he was competing in too crowded a market–he saw off his rival Herr Lampert, but Soyer’s book came out the same year as Vera Countess Serkoff’s Paper-Bag Cookery and one year before Emma Paddock Telford’s Standard Paper-Bag Cookery.

Or perhaps Nicolas Soyer’s greatest obstacle was that he stood in the shadow of a giant: his grandfather Alexis Soyer, the celebrity chef of the 19th century. At age 20, Alexis Soyer was cooking for Prince Polignac, the French prime minister. He served breakfast to 1,300 for Queen Victoria’s coronation. He produced several cookbooks and his own range of bottled sauces. He also pioneered the water-powered refrigerator, the gas cooker, the adjustable temperature oven, the portable table-top stove, restaurant meat safes and fish slabs, the cafetiere, and the cook’s timer. Oh, and it was he who introduced fish and chips to England.

As if that wasn’t enough, Alexis’ ingenuity prevented hundreds of thousands of deaths. After his wife died of fright during a thunderstorm, motivated by her ill fortune he sought to feed London’s poor from mobile facilities. At the height of the potato famine, he went to Ireland to set up the first soup kitchens, serving free food to thousands every day; to raise money for those afflicted, he also published what may have been the first charity cookbook, which sold more than a quarter of a million copies. Then, hearing of troops in the Crimea dying in droves of malnutrition, food poisoning, and cholera before they even reached the battlefield, he rushed off to the war zone and worked with Florence Nightingale to improve diets in military hospitals. While there, he invented the army field kitchen, educated soldiers on nutrition, and trained and installed a cook in every regiment.

In comparison, paper-bag cookery was never going to cut it. Still, at least if I ever find myself in a situation where I am forced to make stewed kidneys with nothing but a paper bag on hand, I’ll be prepared.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Histories of”¦ section, which looks at stories of innovation from the past. Click the logo to read more.