The latest in lunar politics–the landing of China’s Chang’e 4 spacecraft on the moon’s far side–has spurred headlines to wax on about the mysterious “dark side of the moon.” Such descriptions remind me of 14th- and 15th-century European maps on which places that had not been reached by European ships were marked as uninhabitable, godless pits. The words “dark side” are as inaccurate as the old maps: the far side of the moon receives its share of sunlight. The Chinese lunar rover has instead landed at the edges of the map, carrying the first of Earth’s life-forms to live and die on the moon: cotton seedlings, which sprouted there, then quickly met a chilly end.

This move to the moon from an increasingly bordered and burning world might yet light the way for humanity to sow life (and extract resources) throughout the stars. The first human craft to make a soft landing in this region of space, Chang’e signals that a new contestant has arrived in a space race that’s still running in accord with a 1960s-era objective: the journey is not all spectacle or science, it’s also a path to postapocalyptic economic dominance.

The probe landed in the 110-mile-wide Von Kármán crater, itself situated within the largest and oldest impact crater on the moon’s surface. Some scientists believe that this area of the moon could be richer in mineral resources than previously explored regions. And a mineral-rich moon could provide future energy supplies for a madly whirring Earth, or fuel the ships of Mars-bound colonizers. For now, space programs that seek economic and spatial dominance must rely on military support and heaps of material wealth.

Yet there are other ways to dream of the moon. And some arise from smaller countries cut apart or left behind by the past and present colonial machinations. Even after the failures of the postcolonial and countercultural revolutions, outer space remains a site tangled up with dreams of national freedom. In the 1960s, the lesser-known space programs of Lebanon and Zambia offered glimpses of how utopian plans for a changed geopolitical world had their corollaries in a larger cosmos. As above, so below: these efforts presented visions of a more equitably distributed universe of resources.

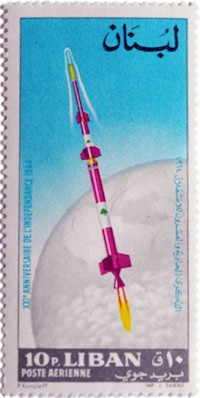

The Lebanese space program was born in 1960 from a science club at a university in Beirut. At its height, in 1963, it launched a rocket whose altitude approached that of crafts in low-earth orbit.

Called the Lebanese Rocket Society, the program had help from the Lebanese army, which provided space and access to materials. Ultimately, though, the military was kept at a distance by the program’s founder, scientist and professor Manoug Manougian, who insisted that the society remain educational.

Manougian now suspects that, because of his interest in the stars, he was being surveilled by foreign agents from the U.S., Britain, and possibly Israel. When he was approached by a nearby nation (left unnamed by Manougian) to contribute to its weapons programs, he decided that it was time to fold the project. The work of the Lebanese space program was for students of the cosmos, not of war.

More than 50 years after the Lebanese Rocket Society folded, what remains of “the forgotten space program” is a documentary film and, in the Lebanese city of Tripoli, a lotus-shaped helipad standing in the city’s futuristic fairgrounds, which were designed by the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer. Once meant to house a space museum, the helipad–and the fairground itself–is a monument to possibility, a rare public space in a city with few parks. Construction of the fairgrounds halted in 1975 with the outbreak of civil war, and the structures there now echo a past future as well as the cries of those tortured and executed during the war.

The project pursued by Manougian and his students is not the only unfinished space quest of the sixties. For others, the attempt to reach the stars paralleled the effort to claim independence from Western control of the world’s resources. Frances Bodomo’s short film Afronauts takes us to a scene of such collective dreams. The film takes place on July 16, 1969, but pans away from that day’s Apollo 11 rocket launch in the United States to a simultaneous lunar expedition unfolding in Zambia.

The story is based on the real-life efforts of Edward Festus Mukuka Nkoloso, a school teacher, a member of the Zambian Resistance Army, and the founder of the Zambia National Museum of Science, Space Research, and Philosophy. In 1964, five years before Apollo 11 put two Americans on the moon, Nkoloso dreamed of beating the United States and the USSR there–and sending up teenaged Matha Mwambwa, two cats, and a missionary as the first Earthlings to make the journey. He even imagined this team on Mars. (“But I have warned the missionary he must not force Christianity on the people on Mars if they do not want it,” Nkoloso wrote.) “He sent a lot of people into the desert, and rolled them around in an oil barrel, to feel anti-gravity and weightlessness, and prepare them for space travel,” Bodomo told Interview during the planning process for Afronauts. These experiments never came to fruition, but Bodomo’s upcoming feature film, an extension of the short, looks to represent this other side of history.

The missionary intent of Nkoloso’s extraterrestrial endeavors signals the religious overtones that space travel often takes. In the States, this takes on shades of Manifest Destiny. In Octavia Butler’s Parable series, for instance, such a destiny has a more collaborative than conquering intent. The religion created by revolutionary empath Lauren Olamina in Parable of the Sower preaches that humanity’s destiny is “to take root among the stars” because this is the kind of large-scale group project needed to pause the apocalypse. Yet the character’s eventual success in spreading her Earthseed philosophy is cast in doubt: the rocket that Lauren looks upon at the end of Parable of the Sower is named Christopher Columbus. In Butler’s unfinished drafts for the third volume of the trilogy, a final installment that was to be called Parable of the Trickster, these ambiguities persist; Butler struggled with the many possible ways humans could either create or destroy their new home.

Instead of thinking of space exploration as isolated national efforts, we can view the smaller programs of countries like Lebanon and Zambia as inspiration for new international undertakings. I imagine a tricontinental-style initiative that moves beyond continents to celestial bodies. A solidarity movement across so-called postcolonial societies in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, tricontinentalism focuses on these three locations as the harbingers of a new anti-imperialist solidarity; the movement also encompasses efforts to consider the conditions of internal colonization, including African-Americans and other oppressed groups. During the 20th century, international collaboration on this scale was as historically transformative an event as the lunar landing. After all, the first Tricontinental Conference took place in 1966, right in the middle of the space race.

The theological teleology of Earthseed, which is never settled in Butler’s novels, could be the kernel of another celestial scheme: a utopian blueprint for non-imperialist future-making. What if the decolonial dreams of 1960s movements in developing nations could be achieved by shooting for the moon?

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our “Space” Beat, which asks: If humans are to leave Earth and become an interplanetary species, whose vision of the future will be realized? And who will get to be a part of it? For more dispatches, click the logo.