When Waterloo Bridge was officially opened in 1945, British Labour Party politician Herbert Morrison thanked the men who worked on the project:

“The men who built Waterloo Bridge are fortunate men. They know that, although their names may be forgotten, their work will be a pride and use to London for many generations to come. To the hundreds of workers in stone, in steel, in timber, in concrete the new bridge is a monument to their skill and craftsmanship.”

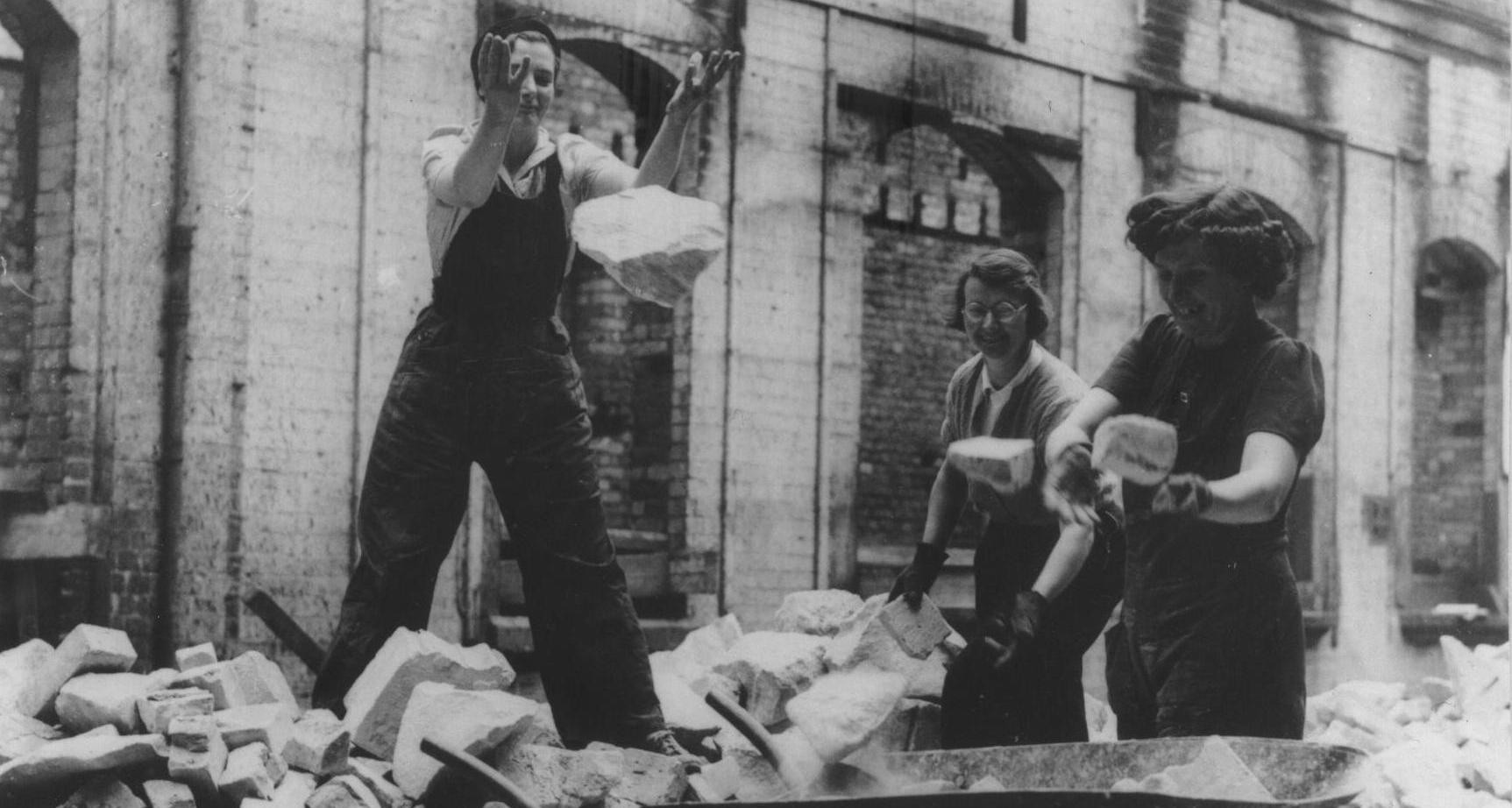

It’s a classic bit of rhetoric in praise of the unknown worker. Except these anonymous laborers weren’t all men. Unbeknown to Morrison–indeed, unbeknown to most people at the time or the crowds that cross the bridge today–it was built at least in part by women.

The tour boat guides on the Thames know this–they call it “the Ladies Bridge.” With men conscripted to the armed forces during WWII, so the story goes, at least part of the work of building a new bridge was left to women.

The story sparked the attention of filmmaker Karen Livesey, who teamed up with Christine Wall to produce a short film about their quest to learn more about the women who built the bridge:

“I’ve always been interested in the subject of what’s men’s work and what’s women’s work,” Livesey told me. “It’s always been a subject that bugged me. I’ve always liked doing things that are considered men’s work,” she laughed. “I reckon a lot of interesting jobs are considered men’s work.”

A friend tipped her off about the boat guides’ story of the Ladies Bridge and she went investigating.

“They were absolutely adamant on the boats,” she said. “It depends which guide you get, but it’s pretty standard that they refer to it as the Ladies Bridge, and then they make some comment about how it’s still amazing it’s standing, considering women were involved in making it, blah blah. But they are really adamant that it’s a fact. So it stuck with me. If it’s a fact, and it’s right in the heart of London, how come it’s not that known about?”

That the story has largely gone untold makes an interesting find for a film, but it’s also proved to be a historical challenge for the same reason. It was hard to find any evidence.

Livesey and Wall started to publicize their search. They put advertisements in magazines, did radio interviews, and worked with networks like dial-a-ride (a transport program for people who can’t use public transportation) and care homes for the elderly.

“As time went on, I began to realize, this is about the search,” Livesey said. “For me, the big thing that came out of the film was that history is about getting the story that you want on the map.”

Part of the problem is the way gender intersects with class. There are records of the female code-breakers at Bletchley Park, even if it’s the men we usually hear about. But people simply didn’t write much about the women working on Waterloo Bridge–the crane drivers, the welders, people heaving and carrying concrete around–and they were even less likely to write about themselves. In many ways, Herbert Morrison had a point about anonymity of such workers (even if he incorrectly assumed they were men).

There’s a bit in the film where Wall talks about how, as an archivist, she was looking for a diary or similar record but realized these women just wouldn’t have done that. After a long day laboring, probably on top of household chores, they wouldn’t have had time. They might well not have thought it was worth mentioning either. “The idea of writing a diary that would be found”¦” Livesey muses. “It reflects a certain sense of being part of history.”

There was also a problem of records getting lost when the the contractor who oversaw the building of the bridge in the 1940s temporarily suspended trading in 1970. And the unions weren’t exactly keen to promote the story either. Women workers were seen as a possible dilution of wage power, because they were traditionally lower-paid. The story of the Ladies Bridge might not have been actively covered up, but there were ways in which it was both allowed to be forgotten and, at times, constructively avoided in conversation.

Inspired by the story, Cassie Robinson and Jen Lexmond of the Point People have teamed up with the Women’s Engineering Society for a campaign to see a plaque on the bridge in memory of the female workers who helped build it.

“I wanted to tell it and find a way to make these women’s contribution visible in a lasting way,” Lexmond told me. As well as simply marking this contribution, Lexmond and Robinson hope it’ll inspire people to remember further stories where the contribution of women has been ignored–be it in construction, in science and engineering, or anywhere else.

“There’s such a gender gap in the stories that we tell–whether in fiction or in “‘fact.’ Too often women’s stories are ignored or unacknowledged,” Lexmond continued. “The stories we tell and imagery we have so strongly shape our collective unconscious–what we think women and men are, can do, can be, can aspire to.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Going Places section, which looks at the impact of transportation technology on the modern world. Click the logo to read more.