Read the next installment: “Future Fragments”

Read the previous installment: “Architects of the Future“

If the 19th century was about the discovery of the future, then the 20th century was about the rapid exploration and exploitation of the future. A century ago, the concept was fresh and exciting, with myriad possibilities unfettered by hard science. Speculation about the world to come reflected contemporary hopes and desires–and sometimes revealed more about the present than the future.

We interpret futuristic images from the past through our own modern subjectivity. Outdated fashion, aesthetics, attitudes, and preoccupations coupled with unbridled optimism can lead us to just see the “kitsch”: it’s easy to dismiss these images as retro curiosities, or a collection of predictions that didn’t become reality. As the refrain goes, “Where’s my jetpack?”

But many 19th- and 20th-century artists were surprisingly prescient: for all of the futures that never came to be, you can see precursors of today’s world in many of these images. What did they get right–and wrong? What’s missing in these visions of the future? How did these visions inspire future generations building the world of tomorrow?

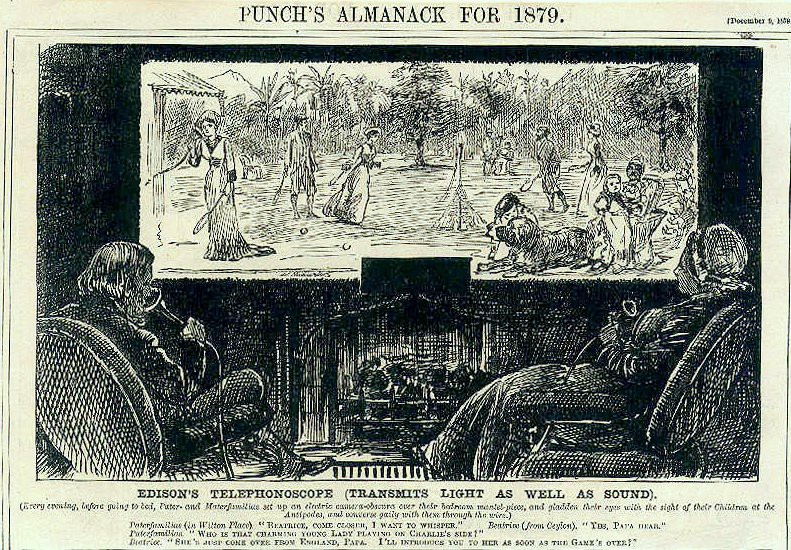

Looking through the wild array of predictions from 20th-century artists, it’s easy to spot recognizable elements. We regularly speak to each other via screens with video and sound. Satellites have changed how we share information on a global level. Disney’s Magic Highway U.S.A. had its self-driving cars–though destinations were programmed by punch cards.

Despite these correct predictions, plenty of things are missing. While ideas about a connected world through screens and telephones have been around for well over a century, the scale of change that computer technology would bring is vastly underrepresented.

Television was ever-present in futurism, but using screens for interactive entertainment was largely absent; even with awareness of the first video games, like 1962’s Spacewar!, knowing that playable experiences would be available in millions of households, would have taken incredible foresight.

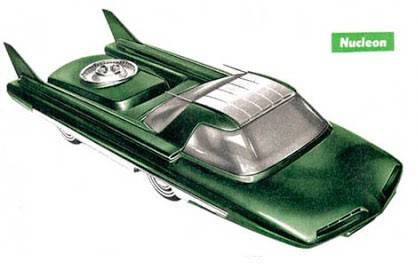

Steeped in optimism, many of these images cast an uncritical eye towards technological progress, with little acknowledgement of contemporary problems. Complex issues like improving healthcare, the effect of automation on employment, or environmentalism and climate change aren’t often aren’t dealt with–though images of solar- or nuclear-powered futures show an awareness of the need to embrace cleaner, more renewable energy sources.

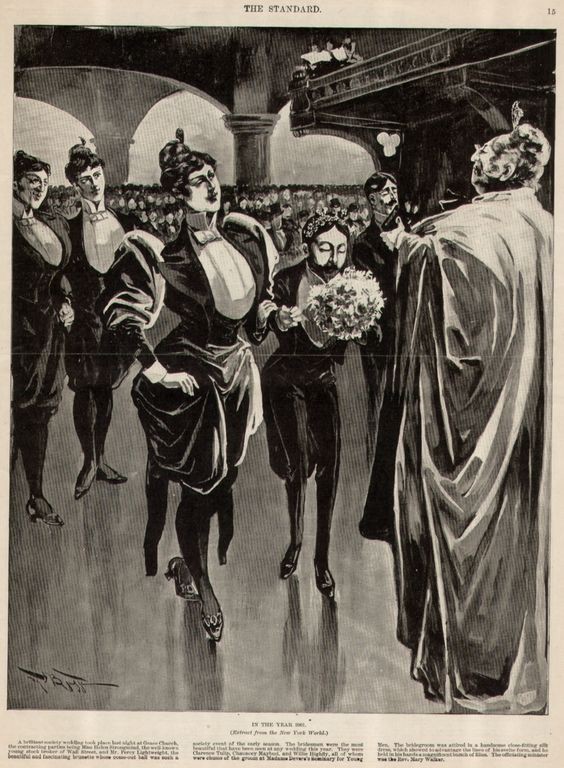

While many futurists projected the changes technology could bring to the physical world, those projections rarely reflected any visible change in society’s attitudes. Instead, these images were more likely to exploit contemporary fears and anxieties. Harry Grant Dart’s “Why Not Go to the Limit?” suggested that giving women greater rights would upend traditional gender roles. “In the Year 2001,” a female priest towers over a bride in a suit jacket while a diminutive groom sports a flower crown and bouquet.

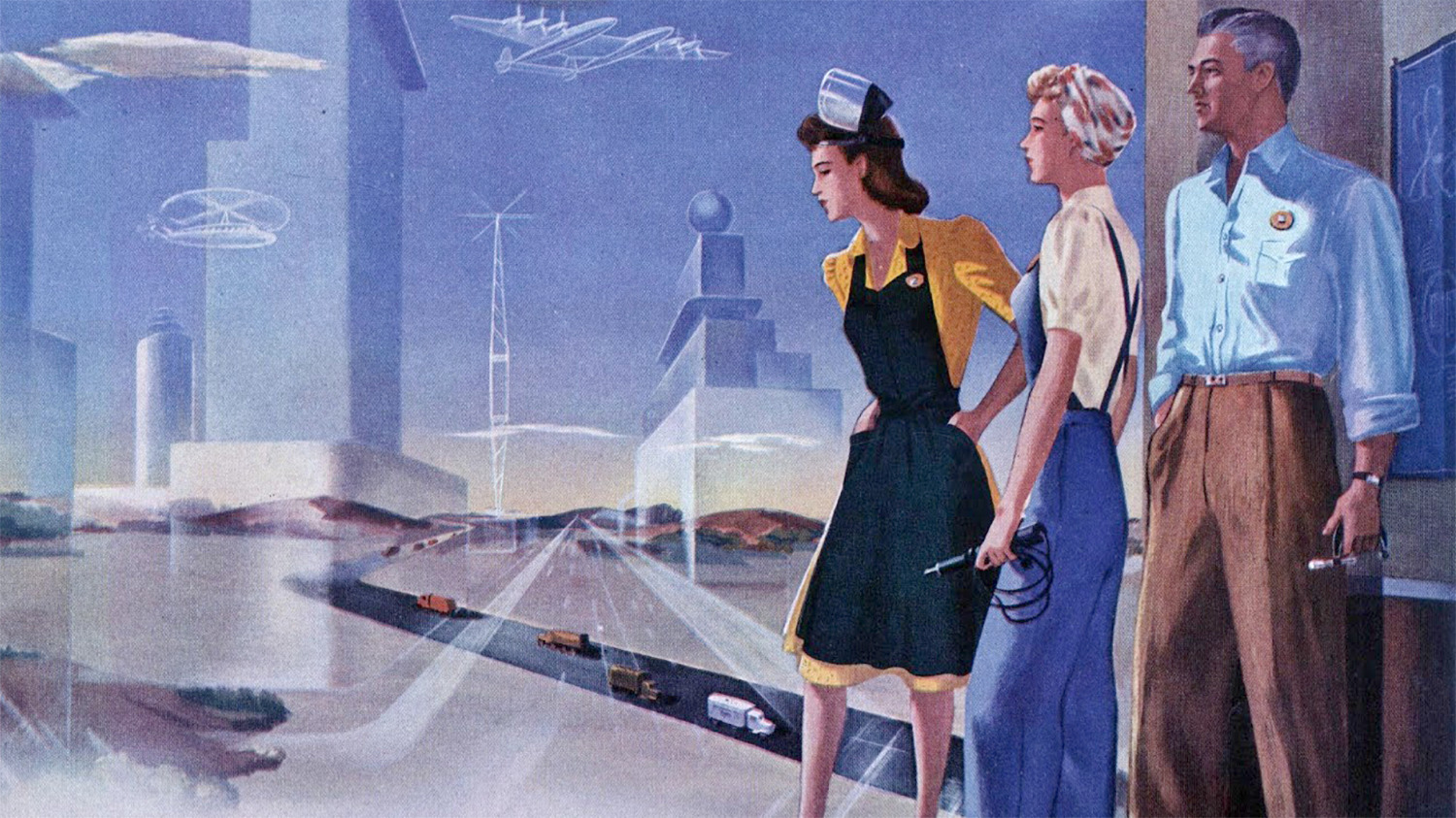

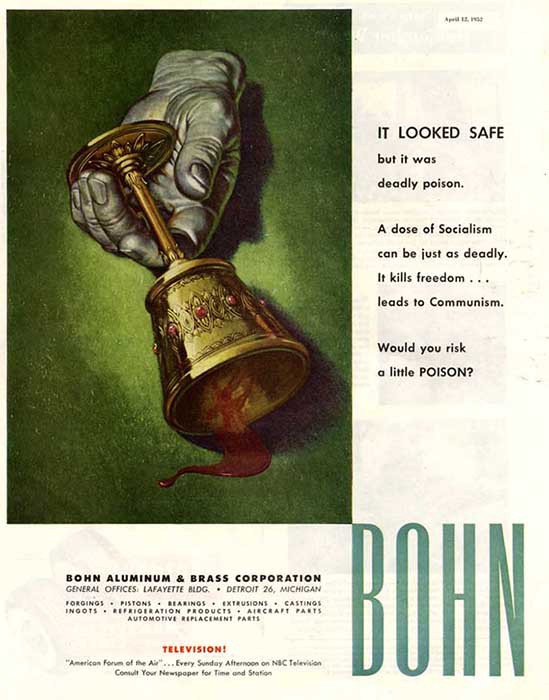

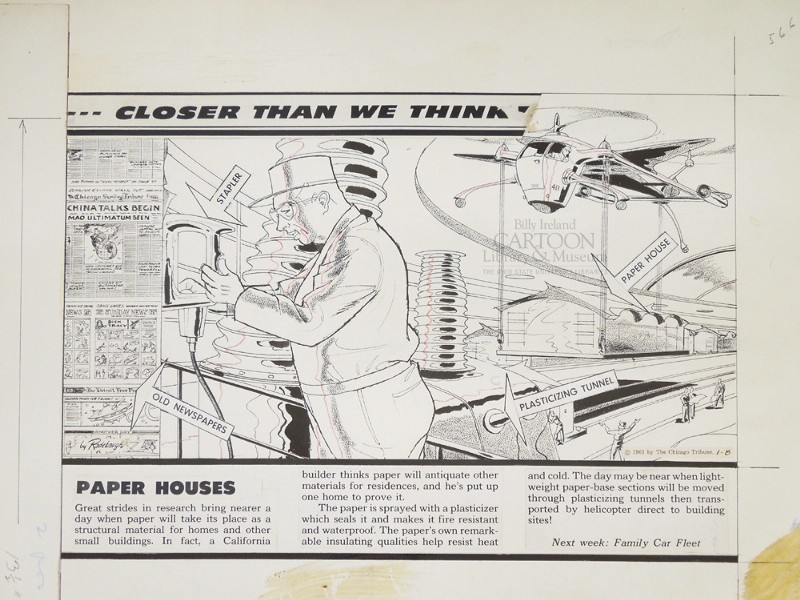

Arthur Radebaugh’s illustrations for Bohn’s futuristic advertising campaigns in the 1940s and 1950s helped shaped how the future looked in the minds of many Americans. But the optimism of this series was countered by another series of Bohn ads that exploited Americans’ Cold War fears about communism: an entire campaign warning against socialism taking hold in Bohn’s factories.

In many futuristic images, attitudes towards women were firmly rooted in the established gender roles of the time. In middle-class family units, women either play mother or secretary to men, who take the role of father or boss.

One of the most striking things about many of these images is the complete lack of racial diversity in the future. In an era of legal segregation, most images of the future reinforced rather than challenged the status quo. When characters of color were depicted, it often sparked controversy.

In 1953, the science fiction comic anthology Weird Fantasy published “Judgement Day” by Al Feldstein, Joe Orlando, and Marie Severin. Humans have colonized distant planets using artificial robot life based on human traits. When a human astronaut finally arrives thousands of years later, he finds a planet segregated into privileged orange robots and an underclass of blue robots who have to be “kept in their place.” The allegory to racism is obvious, reinforced in the final panel, when the astronaut removes his helmet, revealing that he is black. Charles F. Murphy, head of the comics watchdog Comics Magazine Association of America, demanded the black astronaut be removed from the story; the publisher refused.

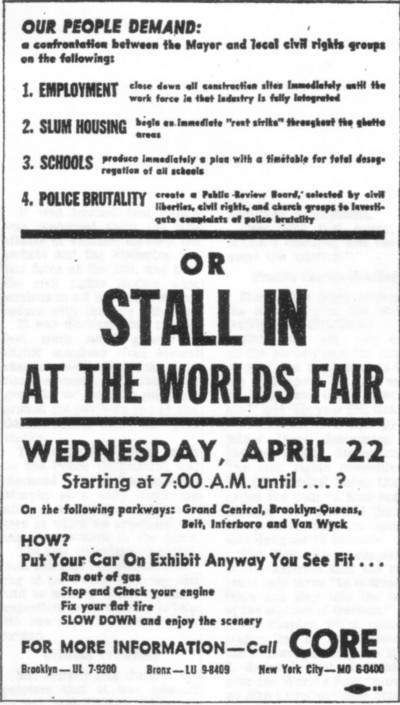

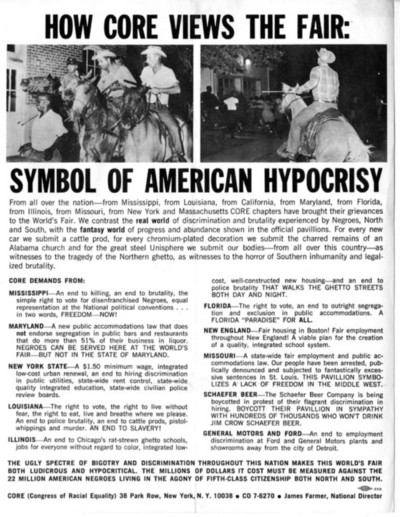

But for many activists of the Civil Rights Movement, the idea of celebrating “the future” itself was subject to critique. In 1964, the Brooklyn branch of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) proposed a “stall in” protest at the New York World’s Fair, blocking approaching roads with “stalled” cars on the fair’s opening day.

“We contrast the real world of discrimination and brutality experienced by Negroes, North and South, with the fantasy world of progress and abundance shown in the official pavilions,” CORE’s protest flier read. The group wanted to highlight the hypocrisy of the utopian future depicted at the fair and the stark reality people of color faced daily in the city, demanding integrated employment, desegregated schools, and a review of police brutality.

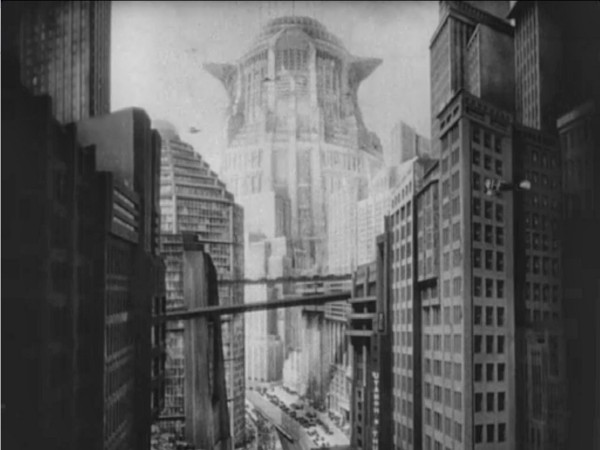

Over the course of the 20th century, the ways artists could share visions of the future changed dramatically. Magazines and newspapers were the primary media; but cinema played its part, and the iconic production design of early films like Just Imagine and Metropolis created a lasting influence on the films that followed.

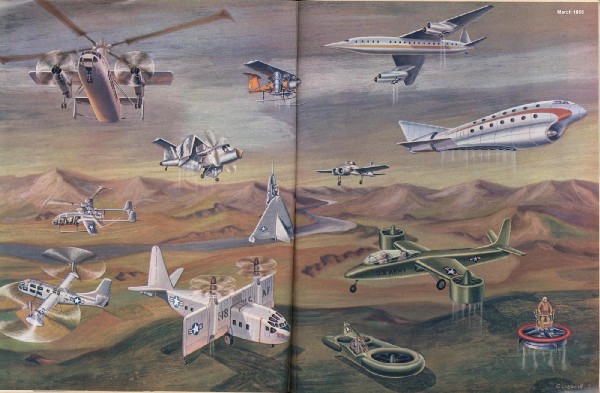

With pencil, brush, and airbrush, 20th-century artists were integral to anyone who wanted to visualize the future, from advertisers to industrialists to governments. As illustrator and concept designer Syd Mead said of the era, “This was before computer rendering, so I was the only one who could do this precise, artistic painting of a nonexistent building.”

Magazines like Time, Life, and Fortune devoted serious investment to illustration and the power of the visual image, especially in science education. An artist presenting a complex subject would be given time to study the topic, sometimes making studies on location. Their illustrations needed to be both accessible to readers, and accurate: images went through a rigorous fact-checking process, in some cases for national security purposes. Assignments could take months, often at considerable expense to the publications.

Eventually the future began to catch up on the illustration business. Color photography became more prevalent, and budgets once spent on magazine ad campaigns increasingly went to television. Film and computer imagery created increasingly complex worlds that would shape the future in the public consciousness. Illustration’s role in futurism began to look outdated, and as time passed what was once cutting edge began to be seen as kitsch.

“The future arrives in bits and pieces, constantly. The future doesn’t start from zero, it starts with the entire accumulation that is represented by “‘now.’ What we do now actually invents the future.”

Syd Mead, from a 2010 interview

The postwar wave of optimism about the future eventually began to subside. Excitement about the Space Race was tempered by the Cold War that was intrinsic to its development. Utopian ideas about the future began to be feel out of date in a more cynical age. Fictional dystopias became increasingly mainstream, with increased fears about war, pollution, limited resources, and the idea that technological progress comes with consequences.

Today, our ideas about the future are less tied to personal helicopters and robot hedge cutters and more to personal electronics and the startups of Silicon Valley. We are pushing up against the current boundaries of the digital world, from AI to virtual reality, to the algorithms that power self-driving cars; and against the physical boundaries of Earth, as we look towards space. Many of our current visions of the future are far less fantastical, grounded in the realities of climate change, managing a future world of extreme weather and rising seas.

Even if our present–and our future–looks different from these past images, the legacy of these artists remains. But no matter how widely their work was consumed, many of these artists are largely unknown today. Arthur Radebaugh spent his whole career giving the future form and shape, and getting the public excited about science and technology. He ended his career painting furniture, virtually forgotten.

But even if the artists themselves have faded into obscurity, their images left a lasting impact on public consciousness. Claims that their visions of the future were directly responsible for any particular innovation would be highly contestable, but looking for direct correlations would miss the point about the role that they played: their work wasn’t about accuracy, but about inspiration. They pointed the way to the possible, and that, in turn, helped create the world to come–the world we know today.

Read the next installment: “Future Fragments”

Read the previous installment: “Architects of the Future“

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. A Visual History of the Future is a five-part series on the way artists’ visions of the future shaped the world we now know.