Norway is the first nation in the world to announce a plan to turn off its FM transmitters in favor of Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB) technology, marking the end of almost a century of high-fidelity sound over broadcast radio. But the story of FM’s inventor is actually one (tragic as it is) that’s worth telling.

Edwin Howard Armstrong was born in New York to John and Emily Armstrong in 1890. He was a shy child, who didn’t make friends easily–an illness he suffered at the age of eight that took him out of school for two years and left him with a lifelong facial tic didn’t help. At 14, he became excited by stories of inventors like Faraday and Marconi, and began building crystal wireless sets. He constructed a makeshift radio tower in his backyard and terrified the neighbors by hoisting himself up and down it. At that time, Morse code was the only thing available to hear, and it was so weak that you had to wear headphones in a silent room to make it out. Armstrong vowed to change that.

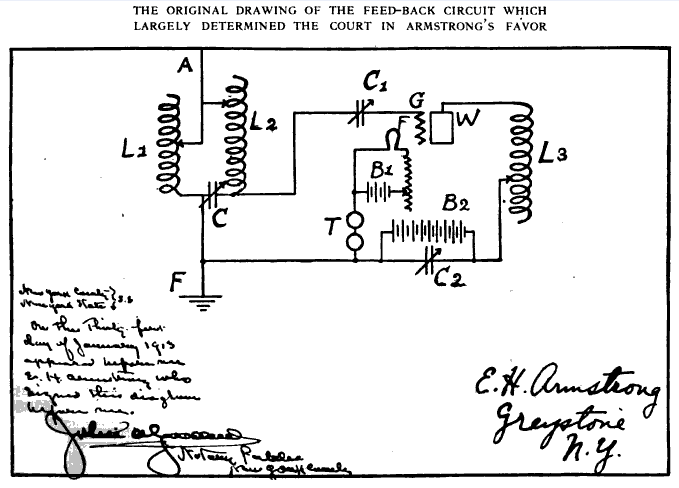

As a student, he joined Columbia’s Department of Electrical Engineering in 1909 and swiftly came up with several inventions crucial to the early days of radio–including the regenerative circuit, which was widely used between the First and Second World Wars. He did most of the work on the regenerative circuit in his parents’ attic, but when he tried to patent the idea his father refused to loan him the money, worried that it would interfere with his progress toward graduation. He borrowed from relatives and friends, and even sold his motorbike, to get together the funds to patent the invention, which dramatically amplified radio signals and could transmit them, too.

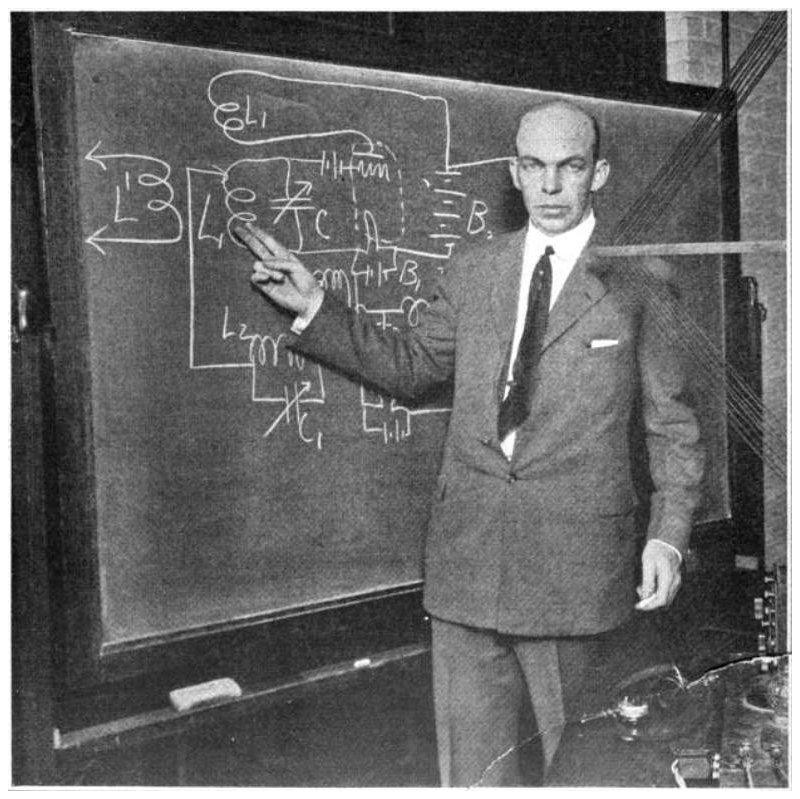

He eventually succeeded in patenting the regenerative circuit in 1913, the same year he graduated. But Armstrong swiftly became embroiled in a dispute with another inventor, Lee de Forest, who’d invented a component called the “audion” that he’d studied for many years. When de Forest claimed that the idea for the regenerative circuit was his, a lengthy court battle ensued. During proceedings, it became clear that Armstrong understood the triode far better than did his opponent, but AT&T was backing de Forest, having already purchased his patents. (While the case spanned three decades, the company’s expensive lawyers were eventually able to sway courts that didn’t understand the technical detail, forcing a Supreme Court ruling in 1934 that favored de Forest.)

While the legal fight bounced from court to court, however, a disheartened Armstrong went back to work and was stationed in France during World War I when he came up with the idea of the superheterodyne receiver–a device that made radio receivers more sensitive and selective, reducing interference between different signals. It was so effective that it’s still used in almost all modern radio and TV receivers, as well as cell phones and other communications devices. It was patented in 1918, and by 1923 he was a millionaire. He gave up his assistant professor salary from Columbia, and in the process was able to drop his administrative and teaching work to focus entirely on research. In Lawrence Lessing’s 1956 biography about Armstrong, Man of High Fidelity, Lessig reports that he was an avid tennis player and drank an Old Fashioned with dinner. In 1923, he married Marion MacInnis, the secretary of his friend and president of electronics giant RCA David Sarnoff. As a wedding present Armstrong built her a portable superheterodyne radio–the first of its kind in the world.

While fighting the legal battle with de Forest, Armstrong came up with another idea to combat the problem of static in AM radio. Instead of modulating (varying) the amplitude of the radio signal, which was susceptible to interference from thunderstorms or machinery, it was based on frequency modulation, or FM. Researchers had considered the technology before, but a mathematical analysis based on flawed assumptions had shown it to offer no advantages. Armstrong rejected that consensus and set to work proving it wrong.

After several years of experiments involving hundreds of electron tubes spread across a large area, he succeeded in showing that a wider band of FM signals facilitated a reduction in static of more than 100 times, as well as far greater fidelity thanks to the wide audio spectrum used. By 1934, Armstrong had patented this invention, too. At a demonstration in 1935, he wowed an audience by transmitting the sounds emitted from pouring a glass of water and tearing a piece of paper–both of which would have been unrecognizable over AM. A jazz record was particularly well received: “If the audience of 50 engineers had shut their eyes they would have believed the jazz band was in the same room. There were no extraneous sounds,” noted one reporter from the Ogden Standard-Examiner. The benefits of FM were clear.

However, Armstrong’s FM revolution caused a rift with his friend Sarnoff, whose secretary he’d wooed a decade previously. Sarnoff’s company, RCA, had built an empire around AM transmission; and FM, while impressive, was a threat to business. Sarnoff refused to support it, choosing not to buy the patents, and focused his energies on another recent invention instead: television. “A new kind of radio,” said Sarnoff, “is like a new kind of mousetrap. The world doesn’t need another mousetrap.”

The dispute escalated, and Armstrong seriously underestimated what he was up against. First Sarnoff asked him to remove the equipment he’d installed on the top of the Empire State Building. Then, the Federal Communications Commission’s annual report to Congress ignored FM completely. Still, Armstrong was convinced it would succeed. He wrote that the only thing that could slow it down was “those intangible forces so frequently set in motion by men, and the origin of which lies in vested interests, habits, customs, and legislation.”

The FCC initially denied Armstrong’s request for an experimental FM station license, until he threatened to take the technology overseas and was granted one. He alone financed construction of the first FM radio station, W2XMN, in Alpine, N. J., in 1937–complete with a huge transmission tower that still stands today. The station used less power than an AM station but could still be heard clearly 100 miles away. RCA finally offered to buy a license to the technology, but Armstrong refused and demanded it pay royalties just as other companies were doing.

So, RCA twisted the saber. The company had been researching FM technology of its own, and soon RCA and other companies were selling FM radios that ignored Armstrong’s patents. RCA claimed the invention of the technology and won a patent of its own. The FCC added to Armstrong’s woes in 1945 by raising the FM band to higher frequencies and reducing the amount of power allowed to a transmitter–a move justified by atmospheric interference and the growth of television, and lobbied-for hard by RCA. The result for FM was severely limited coverage and the rendering of all existing transmitters and receivers obsolete. Armstrong’s radio network didn’t survive the economic impacts of the shift.

Armstrong dug in for a fight. In 1948 he challenged RCA in court, charging open theft and infringement on five of his basic FM patents. The company gathered a battalion of lawyers who began pre-court proceedings, questioning Armstrong endlessly over several years until his health and finances began to deteriorate. Biographers report him predicting, “They will stall this along until I am dead or broke.” On Thanksgiving night in 1953, Armstrong snapped. During a row about money with his wife, he lashed out with a fireplace poker, hitting her on the arm. She immediately left the apartment and moved in with her sister.

He spent Christmas and New Year’s alone. Two months later, on the night of January 31, Armstrong put on his hat, overcoat and gloves inside his 13th-floor apartment. He carefully removed the air conditioning unit from the window and jumped to his death. The New York Times reported on the content of his suicide note to his wife: “He was heartbroken at being unable to see her once again, and expressing deep regret at having hurt her, the dearest thing in his life.” David Sarnoff’s only comment to the press was: “I did not kill Armstrong.”

A month previously, Armstrong had filed 21 patent infringement lawsuits. His wife continued to fight them and, with the help of Armstrong’s lawyer, Dana Raymond, won two and successfully settled the other 19. The money went to the Armstrong Memorial Research Foundation, which initially supported the small FM radio industry and now aims to inspire and reward radio researchers. In 1955, the International Telecommunication Union added Armstrong’s name to its list of greats, and in 1983 a U.S. postal stamp was issued in his honor. He was inducted into the Consumer Electronics Association’s Hall of Fame in 2000.

Despite his vital contributions to modern telecommunications, Armstrong is still not well known. In Columbia Magazine, biographer Yannis Tsividis attempted to answer the question of why, writing, “The answer is ironic: Armstrong was all substance and no style. He could not play public relations games and was naive enough to underestimate the power of those whose interests were threatened by his inventions. At the same time, he refused to compromise. In the end, he fell victim to the very stubbornness that made possible his spectacular technical successes.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Histories of”¦ section, which looks at stories of innovation from the past. Click the logo to read more.