Art historian Gavin Grindon first spotted DIY gas masks last year, looking through photos of the Gezi Park protests in Turkey. He was developing an exhibition on the art and design of protest, and was intrigued by a street-based response to tear gas: essentially a surgical mask stuffed inside a sliced plastic bottle, with some insulating foam and elastic added for good measure.

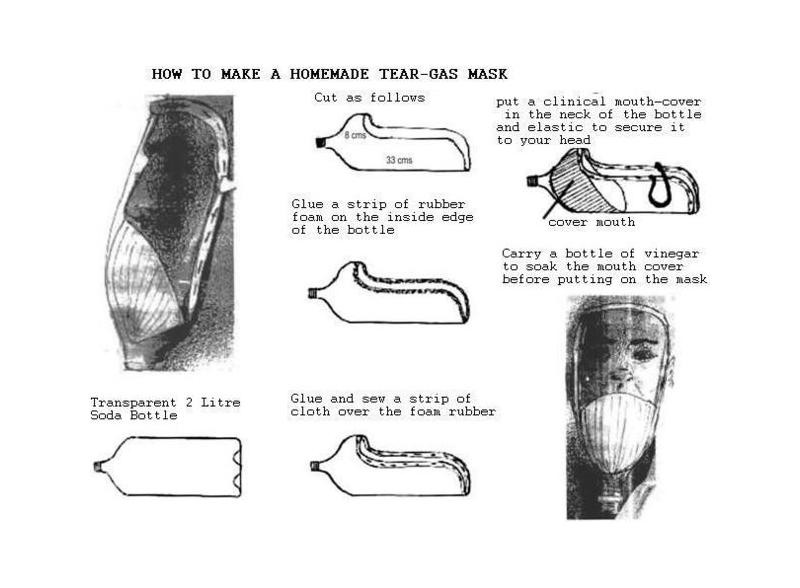

“As far as I can tell, it was playing around with what [protesters] had on hand,” Grindon told me. The trick of soaking cloth in lemon juice or vinegar has long been used by protesters to protect themselves against tear gas. But Grindon believes that as tear gas is being used more and more, people are looking for something more powerful. (For instance, Greek activists are experimenting with antacid medicine as more effective than vinegar.) For his part, Grindon imagined he could use a rough how-to guide for the bottle-based idea he found pinned to a wall in some photos to design something even better.

On a hunt for other designs, Grindon found one shared during Occupy Wall Street around the end of 2011, though it’s not clear where its blueprint first emerged. He also spotted photos of a modified bottle-mask used in Venezuela, with two smaller bottles sticking out from a larger one. Grindon was skeptical of how well it works, though. “There’s a double layer of filter, but this also doubles opportunities for particles to get in,” he said. The guide Grindon saw in photos of Gezi Park was in Arabic and, after some investigation, he thinks it came out of Syria. He found an image of a 74-year-old soldier describing a similar design in use in the country; it’s from 2013 but seems to be of an earlier incident. Even more, he found a video from May of 2011 showing how to make a more complex mask, filled with cotton wool and charcoal as a filter.

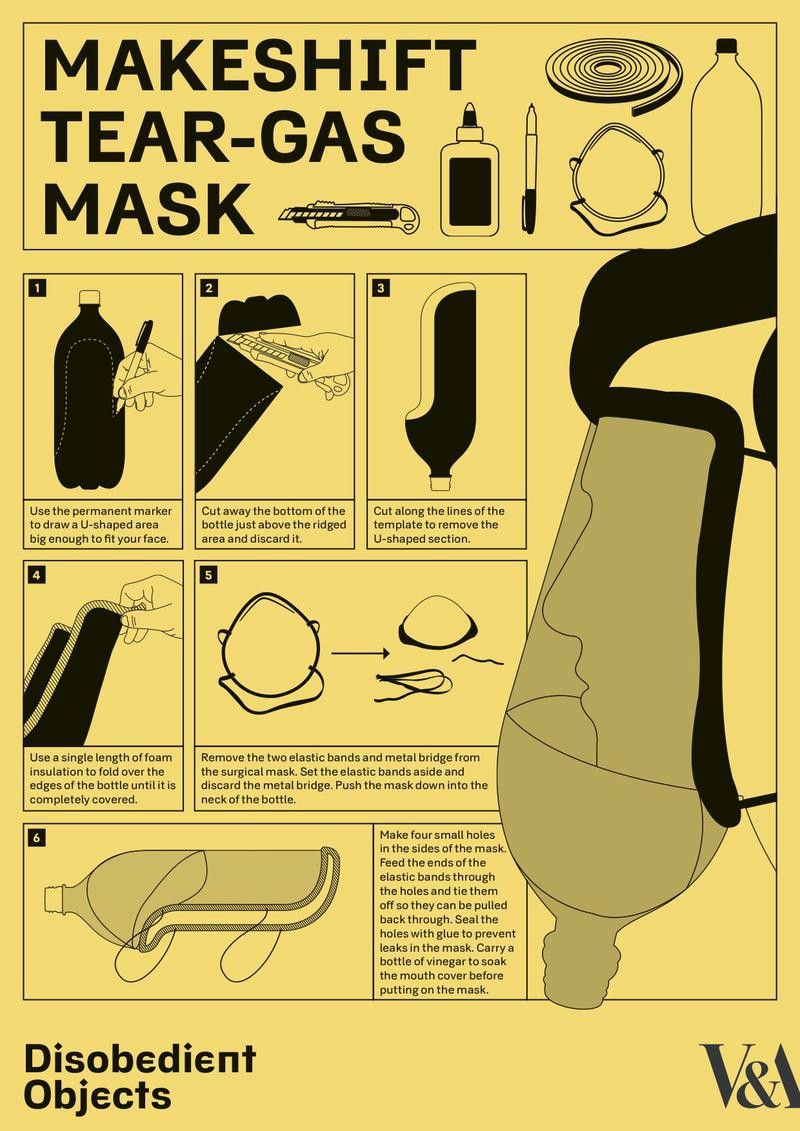

Grindon and his colleagues at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) went to work making their own mask and how-to guide. They spent time working out the best version of the designs, and the cleanest way to communicate it. The result is currently on display as part of the Disobedient Objects exhibition with the guide available for download. The how-to is also the cover of the exhibition’s book and was used on a promotional poster. It’s become part of the exhibition’s branding.

After the exhibition opened in July, Grindon started to see the how-to guide blogged around a bit. “I saw a lot of people sharing the masks who thought it was a cool thing and maybe weren’t connecting it [to something bigger],” he said. Moved into the rarefied halls of the V&A, perhaps it had become a fashion item–this year’s Che Guevara T-shirt. But even before the V&A picked up the idea, the website Treehugger described it as “the perfect accessory for the revolution,” because it is “cheap, easy and kinda cool.” It was also featured on a Zombie survival site.

It’s easy to see why people are interested in the mask. The ingenuity of it is appealing. It does look edgy and artful. But Grindon’s aim was grander than that. Then, this August, Ferguson happened. Grindon quickly saw the guide popping up alongside the trending hashtag, and the V&A saw a large spike in web traffic. A Twitter user contacted Grindon to say a group was using the design for a mask-building workshop. Separate from Ferguson, Palestinians began sharing it as part of expressions of solidarity–advice about what to do in response to being attacked with tear gas.

Then the design turned up in Hong Kong. “Again, I was just on social media, following a protest, and I saw a picture of someone wearing one and was like, wait a minute, that’s the mask! That’s the mask!” said Grindon. After, he started going through press photos looking for other occurences. He spotted people using cling-film, stretching it across their faces, and was frustrated: “I was thinking, I’ve got a better mask than that! I wish I could post it to you!”

Grindon soon found his guide linked to Occupy Central’s Facebook pages, and recognized that somebody had made a related video. “So I thought, OK, they’re definitely using this guide. And then someone sent me photos of a workshop run by students where they’d made about a hundred of them,” he added excitedly. “It’s a manufacturing line. One person is cutting them out, another is putting the edges on, mass-producing them.” Later, he saw tweets from people saying protestors were distributing masks, in the same way they were handing out food or umbrellas. “It’s a way of looking after your friends. You make them a mask,” said Grindon.

While he still doesn’t know the mask’s originator, Grindon’s iterative design is being used and shared across the world. A tear gas mask that seems to have been used in both Syria and Occupy Wall Street in 2011 was reapplied on the streets of Istanbul in 2013. The next summer, a museum in London formalized and celebrated it, just as Palestinians were sending it back to people in the United States. Then Chinese activists started manufacturing them. Gavin noted a parallel story: “People are also tweeting used tear gas canisters, and trying to work out, who made these?” If the mask sits in a global network, it’s built around networks of the gas itself.

Activists sharing and tinkering with technologies across boarders is nothing new, even if social media speeds up promotion a bit. Grindon offers the example of tripod blockades: three poles with a person sitting on top, a concept originated in the 1989 protests to protect trees in New South Wales. It was soon written up in a magazine, and traveled to the United Kingdom a few years later where it was redesigned for the city using scaffolding poles rather than the materials of a forest. “It’s a filter barricade, it stops cars but still lets through people and bikes. And these three bits of scaffolding with a person on top is what made Reclaim the Streets possible,” Grindon explained. “That whole culture of party and protest is only possible if you clear the road first.” The same 1989 New South Wales protest invented the lock-on, which has since become a common tool of nonviolent direct action.

Where this plastic bottle gas mask goes next is yet to be seen. It’ll go where the tear gas does, Grindon suggested, stressing it never belonged to the museum. “It was just someone else’s story we were trying to tell. And now at this point, it’s out there for people to mess around with,” he said. Most recently in Hong Kong, we’ve seen plastic bottles added to bits of children’s toys to make shields against police batons; maybe that’s where inventive energies are being focused.

For Grindon and his colleagues in London, their focus is on the question of where museums took this story. Social media is a key reason the design circulated so quickly, but Grindon thinks the V&A helped as well. “You’ve appropriated the institution’s ability to project information around the world,” he said. And that’s powerful. He refers to the way museums have traditionally been used as actors in cultural diplomacy. “I was thinking there is an alternative form of diplomacy that the museum is taking part in–without its knowledge and perhaps against its will–where movements around the world are using it to talk to each other and make new things with it,” he grinned. “This is grassroots cultural diplomacy.” It is grassroots technology-transfer, too.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Sartorial section, which looks at the impact of science and technology on how we present ourselves to each other. Click the logo to read more.