Sigmund Freud’s alarm rang at 7 a.m. each morning. He took one hour to trim his beard and eat a light breakfast before seeing his first patient at eight. After lunch, as his son would later recall, he took a daily walk around the Ringstrasse, the road that encircles Vienna’s oldest district, at “terrific speed.” Come 3 p.m. Freud ushered in his second lot of patients, working through until nine, at which point he’d retire to plays cards or, if he was feeling perky, take another walk with his wife and daughter. Freud ended the day by settling down to write journals until around one in the morning.

The French poet Victor Hugo, by contrast, set the gold standard for leisurely toil. Awakened by a gunshot outside his window every day at 6 a.m. sharp, he would slurp two raw eggs for breakfast, then spend no fewer than seven hours drinking coffee and penning love letters to his mistress, Juliette Drouet. At some point during this luxurious warm-up routine, he took an ice bath in a tub of water that had been left out on the roof overnight. After, he headed to the beach for a two-hour exercise regime, before marching directly to the barber for his daily facial tidy-up. Following an afternoon carriage ride with Drouet, at 6 p.m. Hugo would finally sit down to write. Two hours later, he set down his pen. Despite a seemingly languorous schedule, the author published no fewer than 56 works during his lifetime, and many more posthumously.

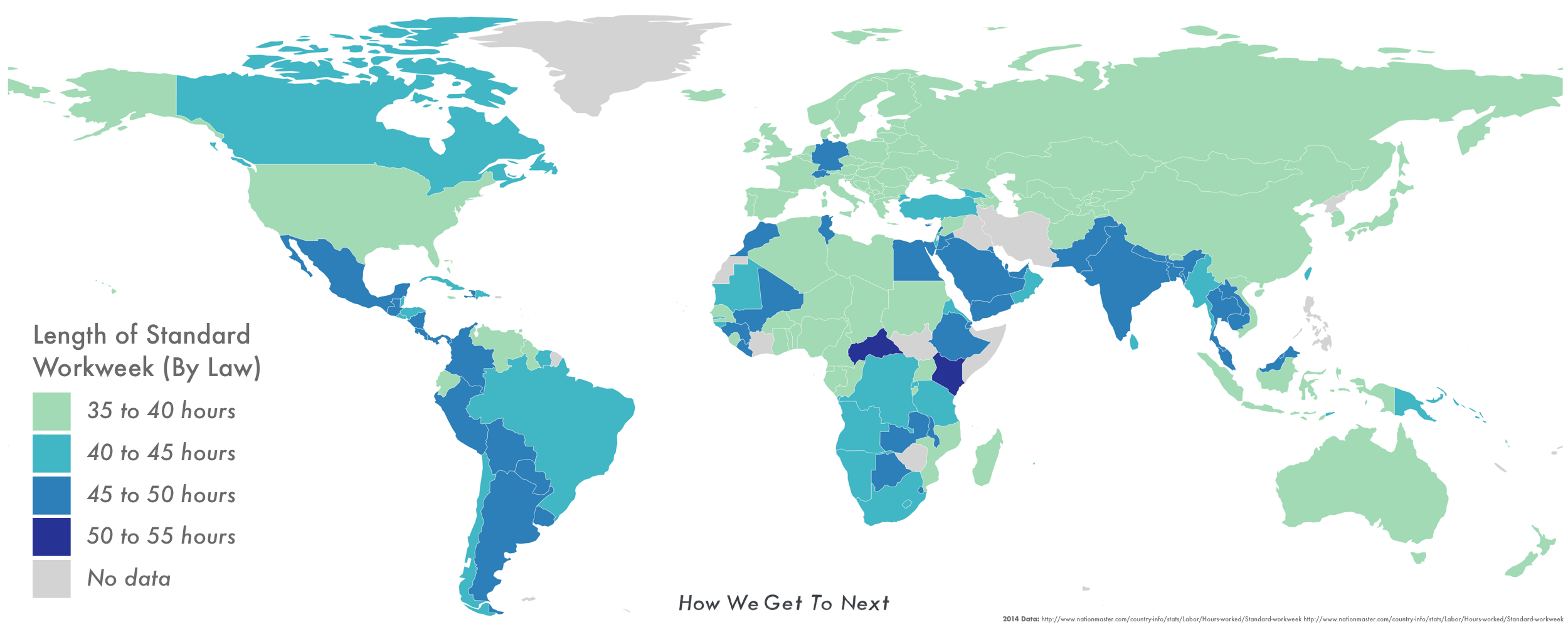

The working schedules of the greatest artists, philosophers, and thinkers can seem highly specific, indulgent, and even partly ludicrous when set against the prevailing 40-plus-hour workweek that has become the routine schedule for our species in the past century. Even more, the idea that many of humanity’s greatest achievements were produced by people who worked no more than four hours a day seems not only counterintuitive, but impossible.

Not so, according to a towering body of evidence in support of workdays that are shorter and more thoughtfully designed in accordance with what we know about the science of productivity. Like emergency doctors or firemen, many of us today are perennially on-call. Even for those who attempt to keep regular hours, the email plague–delivered incessantly to the smartphones appendaged to our bodies–has breached those once firm boundaries that separated work from leisure time. It isn’t entirely surprising that this kind of behavior looks nothing like the blueprint for an ideal workweek.

We live in a culture that venerates overwork–with corporations that often reward those willing to sacrifice their health and well-being for a company’s vision. In 2016, by way of illustration, 55 percent of Americans left a combined total of 658 million days of annual leave untaken. This, even as one longitudinal study revealed that men who don’t take vacation are 30 percent more likely to have heart attacks, and another which found that among rural working women, those who neglect to take days off are more likely to suffer from mental health problems.

Not only is overwork a health risk–a Stanford University meta-analysis of 228 studies showed that high job demands raise the odds of physician-diagnosed illness by 35 percent and long working hours increase mortality by nearly 20 percent–it is also, ironically, a work risk. Anders Ericsson, professor of psychology at Florida State University and one of the world’s leading researchers into the psychological nature of human performance, carried out numerous experiments in his laboratory that showed people can commit themselves to only four or five hours of concentrated work at a time before their productivity levels are ruined.

While researching his recent book, Peak: How All of Us Can Achieve Extraordinary, Ericsson studied how Nobel Prize-winning authors organize their schedules. “We found that they spend roughly around four hours a day writing, and the rest of the day recuperating and preparing for their next writing session the following day,” he tells me.

This pattern, Ericsson says, is also reflected in the schedules of successful musicians and athletes. “These individuals are highly motivated to reach their highest level of performance and realize that they can only concentrate maximally for around four hours a day, often broken down to hour-long sessions with 15- to 20-minute breaks.”

A huge collection of research by other scholars backs Ericsson’s conclusions. A five-day workweek packed with extended working hours is, few experts dispute, suboptimal. A 2009 study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that those who worked 55 hours a week performed more poorly on some mental tasks than those who worked just 40 hours. A Harvard Business Review article touted the idea that, like middle-distance runners, people work best in 90-minute bursts, followed by periods of recovery. This allows our work schedule to synch with our bodies’ ultradian rhythms, the 90- to 120-minute cycles during which our bodies slowly move from a high-energy state of alertness into a physiological trough.

Some courageous companies have tried the approach. Employees at the technology firm Basecamp now work four-day, 32-hour weeks for six months of the year. The company’s founder, Jason Fried, has said that when employees have a compressed workweek, he’s seen them become better at prioritizing, while the quality of their work improves. In 2014, Professor John Ashton, president of the U.K. Faculty of Public Health, said that a four-day workweek could help lower blood pressure, increase mental health among employees, and reduce unemployment. The positive effects aren’t limited to adults, either. A study published last year found that test scores among fourth and fifth graders in Colorado increased by as much as 12 percent when they attended classes for just four days, compared to children who attended for all five.

For the working classes, the five-day workweek was, initially, an improvement. In the 19th century, factory workers typically worked 12″”14 hours per day across a six-day week, taking only the seventh day off for either religious devotion or alcohol-fueled merriment, depending on their upbringing or temperament. Many would drink themselves into a stupor on Sundays. Since enough hangover-laden workers would miss work on Mondays to recuperate, a group of factory owners agreed to give their staff Saturday afternoons off in exchange for a guarantee they’d show up for work at the start of the following week.

In the early 20th century, a New England spinning mill became the first American factory to institute the five-day week, a concession designed to accommodate Jewish workers who wanted to observe the Sabbath but whose Christian employers did not want them to make up the time on Sundays. During the Great Depression, when shorter hours were understood to spread what work remained among a greater number of people–helping to remedy unemployment–the two-day weekend became a fixture.

While religious beliefs incited the shift to a five-day working week, it was industrialization that made it commercially feasible. Through machinery, factory owners were able to maintain or improve their company’s output, even as their employees spent less time at the workplace.

Many observers at the time spotted a potential trajectory toward fewer working hours. In 1928, for example, the British economist John Maynard Keynes wrote that technological advancement would bring the workweek down to 15 hours within 100 years. Perhaps due to lingering religious notions that idleness is a sin, Keynes has, to date at least, been proven wrong.

Widespread change to our working schedules has been precluded by the fact that it would require a majority of companies to make the change simultaneously. If not, those who switch first may be at a commercial disadvantage when compared to those who continue to work a five-day week–perhaps infuriating their clients when, for example, nobody’s around to answer emails on a Friday. Change, however, may soon be forced upon us. And this time it’s being led not by the need for religious observance, but by the machines themselves.

Much has been written about the disruptive effects of increased automation, and most of it in the vein of scaremongering. A 2013 paper from the Oxford Martin Programme on the impacts of future technology claims that, within the next 20 years, computers will be able to replace humans across an astounding 47 percent of all current U.S jobs.

“An enormous swathe of employment is at risk of computerization during the next decade due to new technologies,” says Michael A. Osborne, an associate professor in machine learning at the University of Oxford and co-author of the study. “It’s thanks to a fortuitous confluence of a range of different technologies: mobile robotics, the rise of big data, information, technology, and the cost of components.”

It is a change that will bring with it, among other things, a vast upheaval to the already-endangered “typical” workweek. “One consequence of automation is that human jobs will splinter into smaller tasks,” Osborne says. “As equipment takes on more tasks traditionally carried out by humans, we will begin to specialize in particular components of a broader project, the schedule of which will be dictated by the machine.”

Offering a website design project as an example, Osborne notes that while many of the tasks that go into creating a major website will be automated in coming years, some components, particularly those related to creative intelligence, will still require human work.

These tasks may be outsourced by an AI “project manager,” likely via so-called “e-lancing” sites, where regretfully titled “e-lancers” can sign up for short-term projects. “We will become slaves to global network products, following the timetables dictated by the system,” says Osborne. “The idea of working traditional hours may even disappear.”

While the concept of becoming underlings to an AI boss may sound demeaning, we might actually see positive effects in some areas of work. “There is an argument that automation can promote “‘worker dignity’ by automating work that does not utilize the full cognitive or physical capabilities of a human,” says Mark Riedl, a professor at Georgia Tech University. For example, robots will be employed to work on even more so-called “4D” tasks–those that are dull, dumb, dirty, or dangerous.

When machines can supplant humans in these areas of labor, the benefits to our species are clear. As in the formative days of industrialization, it may even have the effect of shortening the typical workweek again. In Osborne’s view, “It’s not there won’t be any form of work. But as in the years following the Industrial Revolution, the nature of our work and our working schedules will change. It will favor tailored, personalized services. There will be things for people to do, arguably more pleasurable things, as creative and social work is the stuff humans enjoy most.” That means that even if we have to work seven days a week, it’ll likely be for much shorter bursts of time–more like a Nobel Laureate, you might say.

Of course, without systemic measures to recalibrate the workforce, the disruptive effects could be far wider-reaching than merely changing the times at which people occupy their office chairs. “We are already seeing the phenomenon whereby a relatively small fraction of workers–the most talented or the luckiest–carve off an ever larger slice of the pie,” says Osborne. “This will lead to an exacerbation of inequality.”

To prevent this social upheaval, Riedl argues that companies need to invest in widespread retraining of their staff, preparing them to work in jobs that may not even exist yet. “Robots and AI systems will require human operators–or babysitters,” he says. “This requires a completely different set of skills. One possibility is that more jobs are created, but those jobs go to different people than those displaced. Another possibility is that companies and governments get serious about worker retraining. The U.S., at least, does not have a good record of funding retraining programs.”

In many ways, the coming age of increased automation presents a delicious opportunity. As John F. Kennedy said in a 1962 speech: “If men have the talent to invent new machines that put men out of work, they have the talent to put those men back to work.” And while we’re at it, now, more than ever, is the time to set a more thoughtful schedule for human workers as we retrain them to work alongside machines in new ways.

Our hourly rates could increase, just as our hourly demands fall to around four or five hours a day with ample breaks in between. Freed from the tight constraints of a never-off-the-clock work schedule, our brains will get the rest they require to regenerate for maximum productivity. The amount of time we take off for vacation can be dictated by scientific study rather than social convention.

“Society will have to come to a consensus about how we feel about work outside of normal hours, and develop new norms,” says Riedl. It’s possible that this shift is long overdue. “After all, it is 9 p.m. on a Sunday and here I am, talking to you,” he adds.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our The Way We Work section, which looks at new developments in employment and labor. Supported by Pearson. Click the logo to read more.