Right now, we’re at a tipping point between two concepts that shape how we experience the world–the schedule and the stream. The first has lasted over a century, and the second is barely a decade old. But both have been essential in helping new technologies enter the mainstream; and both have created new forms of public space.

For a new technology to see widespread adoption, it needs a simple idea that acts as a bridge between the old and the new. This helps audiences understand and navigate the technologies, content creators work out how to tell their stories, entrepreneurs decide which investments to make, and government decide whether to introduce incentives or regulation.

The problem with new technologies is that we’re really, really bad at predicting their futures. Our immediate frame of reference is so small, and our experience of time so fleeting, that any attempt to imagine how technologies will develop is bound to fail. We suffer from what Carolyn Marvin, in her book When Old Technologies Were New, calls “cognitive imperialism.” We can only imagine futures which are broad extensions of our own contexts and needs.

Nowhere is this more obvious than when early adopters try to imagine the impact of a technology. Every new breakthrough, it seems, is accompanied by predictions of utopian futures with valuable public benefits. After the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable was laid in 1858, Queen Victoria’s first message to U.S. President James Buchanan imagined a future in which the telegraph was “an additional link between the nations whose friendship is founded on their common interest and reciprocal esteem.” In The Master Switch, author Tim Wu reports how David Sarnoff, the president of RCA and NBC, announced the launch of the first U.S. TV networks in 1939 with an even loftier vision:

“It is with a feeling of humbleness that I come to this moment of announcing the birth in this country of a new art so important in its implications that it is bound to affect all society. Television is an art which shines like a torch of hope to a troubled world. It is a creative force which we must learn to utilize for the benefit of mankind.”

Broadcast television did end up being the most important public space of the late 20th century, but only after decades of struggle. Before saying what he did above, Sarnoff deliberately worked with the FCC to outlaw commercial television networks until his radio empire had managed to perfect its own technology, ensuring it could dominate this second broadcast era just as it had dominated the first. He also fought any suggestion that broadcast networks should provide anything other than commercial entertainment. It wasn’t until 1967, with the passing of the Public Broadcasting Act and the development of NPR and PBS, that the U.S. broadcast ecosystem had networks specifically devoted to the public good. While in the United Kingdom the BBC celebrates its 95th birthday this year, Public Broadcasting in the United States is still only half a century old.

Despite the utopian promises of early pioneers, public spaces do not organically emerge from new technologies. They’re the product of complex interactions between inventors, investors, governments, and audiences. These battles are not just about the technologies themselves, but the concepts and products that connect them with audiences.

In 1893, Tivadar Puskás was a prolific engineer in Hungary, with many patents to his name. But the problem he was solving at the time wasn’t technical, it was editorial. A few years earlier, in 1887, Puskás had invented the telephone multiplex exchange, which vastly increased the potential scale of telephone networks by allowing multiple connections over the same line. This gave him an idea–could this new communication technology be used to send the same message to hundreds or even thousands of people at the same time? Could the future of the telephone be not about one-to-one communication, but about one-to-many broadcast?

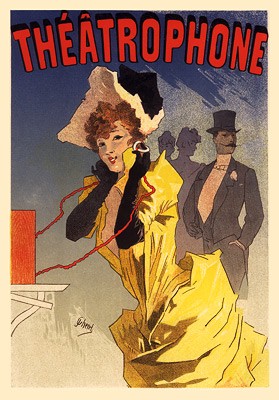

Puskás had seen a similar service, the Théâtrophone, broadcast plays over the telephone network in Paris a decade earlier, but this was tied to the existing performance schedules of the Paris theaters. Subscribers were paying a monthly fee for something that was only active a few hours a night–surely there was no reason why the phone network couldn’t be used to broadcast content throughout the day.

The problem was, telephones had no obvious structure for content. Plays and operas were organized around the social schedules of their bourgeoise audiences, or the amount of time someone could comfortably remain seated in one place. Newspapers and books were limited by the economics of printing and distribution. Puskás had a brand new editorial problem–how to organize stories to be broadcast over a telephone network.

Unlike a theater audience, the telephone audience was not bound by the limitations of being in the same place. But they were bound by time: When they picked up their receivers, they were all listening to the same content as it was broadcast live. This was Puskás’s breakthrough insight–broadcast content could be organized not by space, but by time.

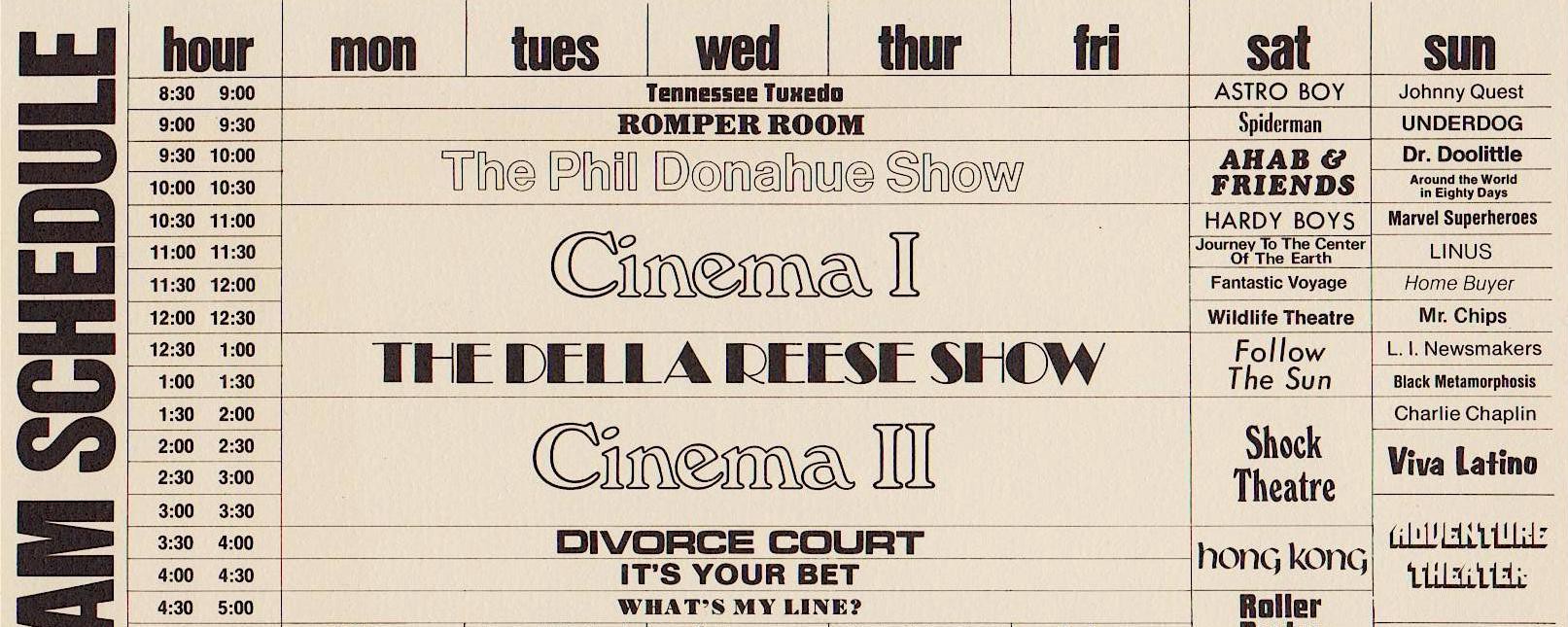

The service he launched in 1887 in Budapest–the Telefon Hírmondó–was the first to use a broadcast schedule structured by the hours of the day. The schedule started at 9 a.m. with an astronomical time check, and then continued with a series of news and feature reports timed to start and end at the hour, half-hour, or quarter-hour, until programming ended at 10 p.m. While newspapers certainly influenced the content genres (Hírmondó roughly translates to “Herald” or “News-teller”), the structure was revolutionary. Nobody had ever had the problem of organizing over 12 hours of human attention before, and the solution Puskás came up with had an impact way beyond the short-lived Telefon Hírmondó. As radio, and then television, grew to dominate mass media, the schedule became one of the most important ideas of the 20th century.

The impact of 20th-century broadcast media was overwhelmingly tied to the power of the schedule–it organized stories that millions of people sat down to watch as one gigantic, communal audience. If you’ve ever worked at a broadcaster, you’ll know that the most powerful people are not the executives or the on-screen talent, but the schedulers. A program lives or dies by schedulers’ decisions to place it in a particular time-slot, based on their assessment of audience habits and the likely competition from other channels at that time. Techniques emerged to manage audiences through a schedule, such as placing a new show next to a “tent-pole” hit so that it might gather some of the same audience, or “hammocking,” where a weaker show is scheduled between two hit shows with the hope that audiences won’t bother to switch over in between them.

The schedule has been such a pervasive part of our culture over the last century that it’s hard to imagine a world without it. Ideas like it are not natural, but invented, refined, and fought over. They are palimpsests of economic needs, cultural biases, and regulatory pressures. If we want them to support new kinds of public space, then we have to fight for that.

Over the last 10 years, we’ve seen the emergence of another of these ideas–the stream. In 2006, Twitter launched, just as Facebook rolled out the newsfeed. Both used similar ideas–organizing stories from multiple sources into endless, personalized lists. Before the newsfeed, following people on Facebook meant going to their individual profiles to see their updates. The feed now plucked these stories from the profiles you followed and organized them into a custom list on your Facebook homepage.

Initially, people hated the new format for a number of reasons, especially privacy. But it soon took off, as people realized it could become an engine for mass movements. Early campaigns that took advantage of it included ones focused on the crisis in Darfur, or street protests in South America, as Facebook’s chief product officer, Chris Cox, recalled in this 2016 interview with Backchannel:

As soon as we translated Facebook into Spanish it was pretty quickly [after] that in Colombia a guy named Oscar Morales organized a group called “No Mas FARC.” This was in 2007.

He said, “You guys have no idea. You have absolutely no idea how important this will be.” He was from a tiny fishing village in Colombia. He had these aerial photographs from Tokyo, New York, Oslo, Sydney, and Bogota. Each had huge amounts of people marching on a single day, carrying a sign that he had designed. He said, “I didn’t spend any money on this campaign. I just used free tools on the internet. I started a group, and 12 million people marched on a single day.”

The feed massively increased the visibility of your network on Facebook, and helped raise the profile of stories that were being shared by millions of people in real time. But this came with a cost: These stories were stripped of their original context. If the organizing principle of the broadcast schedule was synchronization–millions seeing the same thing at the same time–then the organizing principle of the stream is de-contextualization–stories stripped of their original context, and organized into millions of individual, highly personalized streams.

Ten years in, we can see the effects. A culture built around the stream is more open and accessible than one built around the schedule, but stories are atomized, which encourages a spectrum of negative effects from clickbait headlines and fake news to trolling. The Edelman Trust Barometer–an annual survey of people’s trust in institutions like government and the media–reported an “implosion of trust” in 2017, with over two-thirds of the countries in the survey reporting that fewer than 50 percent of people trust institutions. Melody Joy Kramer, in her summary of how news organizations are trying to restore trust with their readers, recognizes that adding more context to journalism will be a key factor:

Perhaps that means thinking more closely about design and editorial choices in terms of media literacy. Maybe that means indicating to readers how many sources were used, or how facts were obtained. Or, if you’re using algorithms to make editorial decisions, maybe that means making that clear and obvious to the reader on every page where the technology is used. Or maybe it means developing more tools like the one The Wall Street Journal made, so that people can realize that what they’re seeing may not be what everyone else is also seeing.

Like the utopian pioneers of broadcasting and other communication networks, we got the future of digital communications networks wrong. The mistake we made was to think that the digital networks’ biggest impact on culture would be abundance. We imagined utopias in which information was free, with infinite copies of everything, distributed seamlessly to everyone.

But the real cultural impact of digital networks is not abundance, but de-contextualization–the transgression of information from one context to another in ways that are out of our control. If you look at the major cultural shocks of the last decade, many of them owe their impact to this de-contextualisation–from Wikileaks and Snowden to personal data hacks and fake news. The last year in particular, with the rise of transgressive, populist politics in the European Union and the United States, feels like an early signal of what culture and society look like when they’re built around the stream rather than the schedule.

The stream is still a young product. It will take decades for the competing forces of money, technology, audience behavior, and regulation to mould its maturation. Like the schedule before it, the stream is an idea that will shift from technology to technology. It’s very unlikely that Facebook will look the same in 20-years time, but it is likely that the stream–a product that organizes stories out of their original context in a highly personalized form–will survive these mutations.

In fact, we can bet that the next versions of the stream will be even more personalized and de-contextualized than Twitter and Facebook. The rise of bots you can talk to, like Alexa and Siri, will take the stream into a purely aural form. If it’s hard to understand the context of stories on a mobile phone screen, how will we understand context when stories are presented to us solely through a synthetic voice? How will Alexa create new kinds of public space?

With the schedule, the battle for public space focused around visibility and representation. As the schedule honed in on just a handful of synchronous stories, campaigners for public media fought to ensure that diverse voices and narratives had visibility within it. This happened with the passing of the Public Broadcasting Act 50 years ago in the United States, and with widespread regulation for public value media in the United Kingdom, from the public charter for the BBC, to the creation of Channel 4 in 1982 as a government-owned, commercially funded broadcaster with a focus on diverse programming.

What will be the battleground for public space in the stream? Like the battle to get visibility within the schedule, it will need to focus on overcoming the stream’s organizing principle–de-contextualization. The tactics public media campaigners have used for the schedule for the last half-century won’t work–it’s impossible to argue for due prominence, or for ratios of representation to better reflect society. Unlike the schedule, the stream is not a single, communal experience, so introducing regulation to ensure diversity within highly personalized, algorithmically curated streams isn’t an option.

Instead, we need to focus on context. We need to analyze the interfaces and algorithms of the stream to see what their cultural and social impact is. We need to challenge developments of the stream that further rip public speech out of context, and actively support projects that help audiences put the stories they discover in their streams back into context. Most importantly, we need to look at our own behavior within the stream. As it’s a performative, oral space, the way we speak, share, and circulate stories has a huge affect on how the stream works as a public space. We need to support behaviors that make context more visible in the stream, like identifying the original creators of content, or identifying the original context of stories before we share them.

This fight for public space in the stream will take decades. There are strong financial interests that are, at best, uninterested in ensuring that the stream works as a public space. Some of the behaviors we have already adopted will have to change, a shift that gets harder as these behaviors are re-inscribed in the products we use every day. The direction of innovation in the stream is moving toward even more de-contextualization, making the fight even harder. And the global reach of the companies developing the stream make it almost impossible for governments to introduce effective regulation.

But it is possible. It took decades of work from activists, foundations, and politicians to create the Public Broadcasting Act in the U.S. Although this will be a very different battle, there is much we can learn from the fight for public space in the schedule. When I worked at the U.K. public service broadcaster Channel 4, it had a particularly inspiring mission statement (and believe me, mission statements are rarely inspiring). It summed up Channel 4’s focus on innovation, disruption, and positive change. I heard its inventor was none other than Mark Thompson, then-CEO of Channel 4, who later went on to become Director General of the BBC and now CEO of The New York Times. Perhaps surprisingly, for someone whose career has been indelibly linked with the schedule, his mission statement for Channel 4 works as a perfect rallying cry for the battle to create public space in the stream:

“Do it first, cause trouble, and inspire change.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Together in Public section, on the way new technologies are changing how we interact with each other in physical and digital spaces. Click the logo to read more.