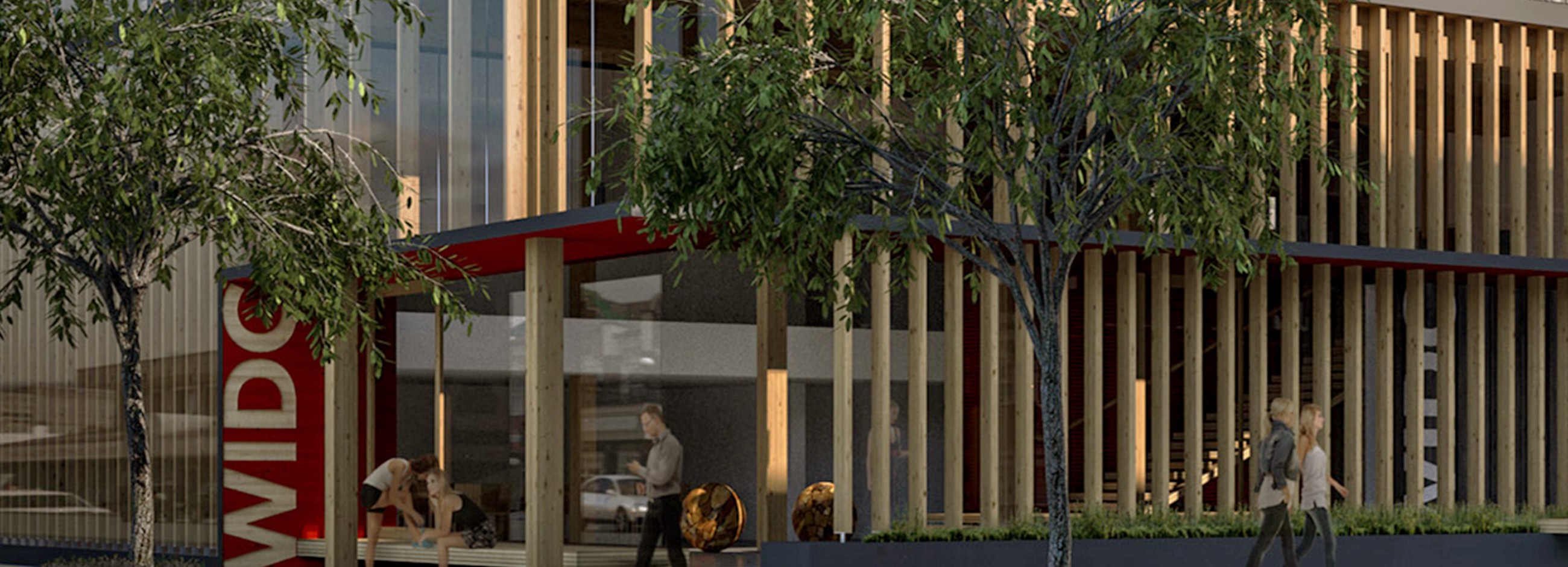

You can huff and puff all you like but you won’t be able to blow down Michael Green’s wooden skyscraper. At 10 stories and 30 meters high, the Wood Innovation and Design Centre in Prince George, British Columbia is the tallest new wood building in the world. “Truthfully, we aren’t really breaking a sweat,” said the Canadian architect. “I’m hoping someone comes out and beats it pretty quickly.”

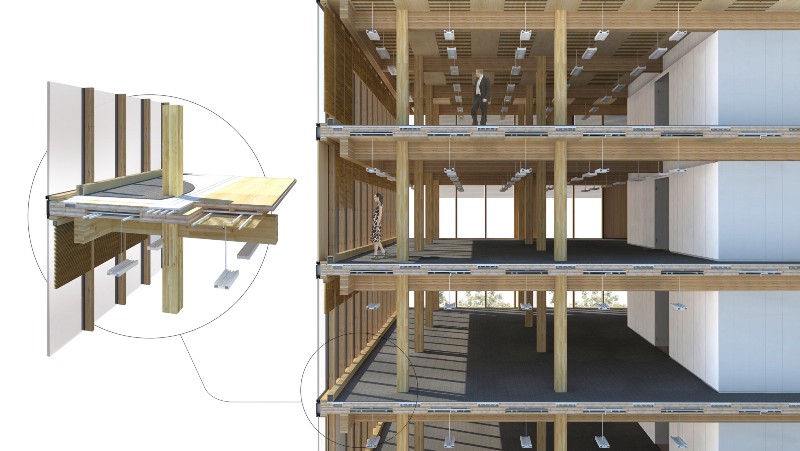

His “plyscraper” is made from cross-laminated timber (CLT) panels and glued-laminated timber (glulam) columns. These are made from cheap, sustainable softwood, glued or pinned together in layers. While the raw materials themselves might be weak, such combination products can be engineered to be stronger than concrete. They resist fire well, charring at their surface instead of catching alight, and can even be assembled, flatpack-style, in a matter of days.

The largest benefit to reaching for the sky with wood, though, is environmental. Products like CLT and glulam are naturally renewable, take less energy to make than concrete and steel, and sequester carbon dioxide rather than pumping out greenhouse gases during their production. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)–which includes the US Forest Service–estimates that a modest four-story building made from CLT would cut emissions on par with taking 500 cars off the road for a year.

Michael Green has made his system freely available as an open source resource for builders, inspiring the architects responsible for the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, to consider a return to mankind’s oldest building material. In a study last year, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill concluded that recreating one of its steel-and-concrete towers with a 125 meter high-skyscraper (40 stories) made largely from timber products is technically and financially feasible, and could reduce its carbon footprint by up to three quarters. “They were trying to match the tower they had made in the 1960s,” said Michael. “They haven’t patented or copyrighted their new timber system. They’ve released it to the world.”

Plyscrapers could even help battle the ecological effects of climate change. Recent mild winters in North America have unleashed an outbreak of voracious pine beetles much worse than anything seen before. The trees they kill are useless for traditional lumber and, if left standing, will eventually either decay or burn fires, boosting Canada’s carbon footprint by 4 percent for at least a decade. However, even this dead wood can be used to make CLT–if it is harvested in time.

While Canada and Europe have been quick to embrace engineered timber products, restrictive building codes in America have limited wooden high rises to just a handful of floors. But things are beginning to change. Earlier this year, the USDA announced a $2-million competition to help developers navigate the paperwork and build the next record-breaking skyscraper. Tom Vilsack, Secretary of Agriculture, said, “There’s a real opportunity for us to restore some vitality to the timber industry in the country, in a way that’s climate friendly.”

Michael Green is now planning a wooden 20-story vertical farm and food hub in Vancouver, and taller projects are being proposed all around the world, including by construction giant Arup in the United Kingdom. “It’s a huge step when we see that kind of commitment from the big players,” said Michael with a smile. “With more players, you say 30 stories, I say 42, and soon it’ll be 46. That’s exactly how innovation happens, with a supportive but competitive spirit. The ball is really starting to roll and it’s not going to stop.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Metropolis section, on the way cities influence new ideas–and how new ideas change city life. Click the logo to read more.