Seven million people died as a direct result of air pollution in 2012. A combination of rapid industrialization and overpopulation in developing countries means that more people are now exposed to toxic skies than at any other period in human history. But the effects aren’t just limited to humans. Indian-crop yields in 2010 were half of their 1980 levels due to air pollution, and subsistence farming in areas within or close to cities is now near impossible for many of the world’s poorest people. In more and more parts of our planet, nothing will grow.

But it’s not the first time we’ve faced this problem. In 1829, a doctor and keen naturalist named Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward was also struggling with keeping his plants alive. He lived in Wellclose Square, close to St Katherine Docks in London, where the city’s air pollution was at its worst; huge chimneys belched out coal smoke and sulphuric acid all day and night. Anything he attempted to grow in his back garden faltered and died.

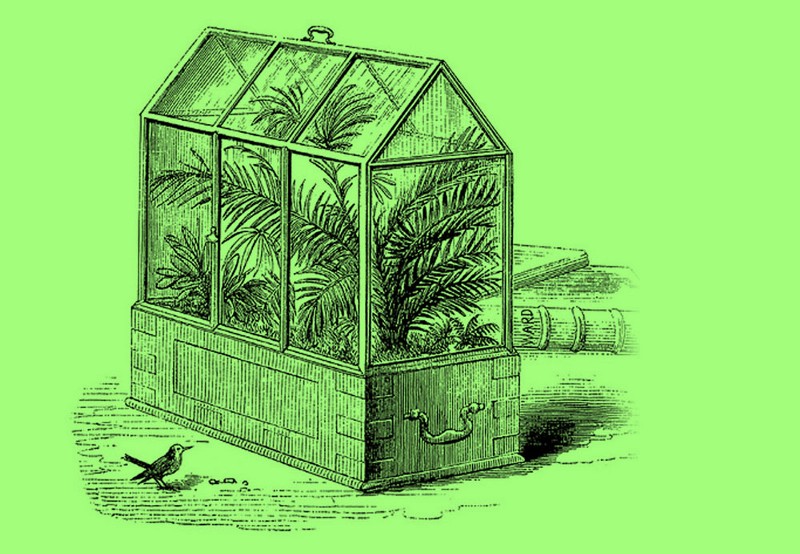

After noticing that grass and fern spores grew without difficulty in the same sealed glass bottles where he kept moth cocoons, he came up with an idea: a closely fitted, glazed case that protects plants from the air outside. He built several and used them to export some native British plants to Australia. Despite months of travel sealed in glass with no ventilation, 19 of 20 arrived safe and thriving, compared to just one of 20 sent without the case.

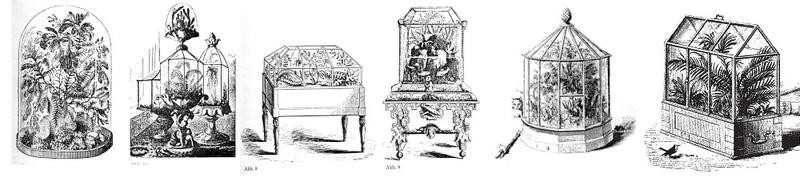

He published his experiment in an 1842 book called On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases, and soon these “Wardian cases” became a feature of high-society drawing rooms across Western Europe and the United States. This was during the days of pteridomania, an intense and widespread public fascination with ferns, which crossed geographical and class boundaries. In 1992, botanical historian Peter Boyd wrote: “Even the farm labourer or miner could have a collection of British ferns which he had collected in the wild and a common interest sometimes brought people of very different social backgrounds together.” Wardian cases became integral to this craze.

They also proved popular on ships where botanists collecting plants from across the globe used the cases to protect their collections from the weather and salt spray while still allowing them to benefit from daylight. The enclosures became crucial to the British plan to break geographical monopolies on agricultural goods; 20,000 tea plants were smuggled out of China in Wardian cases and sent to Assam to begin tea plantations there. A similar scheme saw rubber tree saplings taken from Brazil to new British territories in Sri Lanka and Malaya. There is not a park in London that doesn’t have a plant that arrived in a Wardian case.

These glass structures were obviously the precursor to modern aquaria and terraria, but because of their expense and fragility they’re out of the reach of many of the world’s poorest who live in the areas worst-affected by air pollution. We need something simpler. A flat-packed Wardian Case 2.0, perhaps, made of biodegradable plastic and distributed across affected areas for minimal cost. We could even tap IKEA to build it; the company has recently shown off a flat-pack disaster shelter that’s being mass-produced for the United Nations.

This is no permanent fix to the problem of air pollution, of course, and it doesn’t directly protect people from its effects. Air pollution must still be tackled at its source. But perhaps updating a Victorian innovation for the 21st century could be a small, symbolic step toward that goal, helping the residents of the most polluted places re-green their cities–one plant at a time.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Metropolis section, on the way cities influence new ideas–and how new ideas change city life. Click the logo to read more.