“[T]he athlete as monster comes into existence at the moment when sport is squared, when sport, that is, from a game played in the first person, becomes a kind of disquisition on play, or rather play as spectacle for others and seen by me.”

–Umberto Eco, “Sports Chatter” (1969)

Here’s a premise: Professional sports started its transition into the domain of hyperreality on December 7, 1963, in Philadelphia, at the playing of the annual U.S. Army versus Navy football game.

For all the import that the match carried–the Army-Navy game was the Superbowl of the time–the most exciting feat of the match took place not on the pitch, but in a truck parked outside, which housed a set of videotape decks the size of refrigerators. These would be used successfully just once in the game, in the pioneering moment where a young television producer named Tony Verma gambled his career on a never-before-seen technique: He used audio markers embedded in the tape to cue up and rebroadcast footage of a touchdown just after it had happened. The moment, which would forever change how we enjoy sports entertainment, would go down in sporting history as the birth of instant replay.

Up until that point, watching a sports game on television was only a substitute for physically attending the game in the stadium. Besides being able to enjoy the comforts of a couch at home, there was little to set the experience apart. Technical limitations meant that only a few camera angles were used, and lack of replay meant that any action missed was gone forever. But as technology improved thanks to pioneers like Verna, multiple angles were introduced, replays became increasingly commonplace, and the audience came to expect a different and fundamentally unique experience from broadcast sports.

This relationship was not just one way. An article from the NFL’s Operations blog, titled simply “Impact of Television,“ lays out not just improvements to fan experience, but feedback effects on the way the game itself is played. Slowly but surely, instant replay was used to judge calls, and coaches began using video footage extensively to scout players, analyze their own and other teams’ strategies, and evaluate players’ performance on the field. And these changes were by no means limited to the NFL. In time the NHL and NBA would also start to use replay, and most competitive sports now include at least some level of video adjudication.

“This is symbiosis in action,” writes the author of “Impact of Television” in a candid turn of phrase. “Television’s technological advances, embraced by the NFL, are used to improve the quality of the product the broadcasters are showing: the game.”

Hyperreality is a term for times where fabricated reality seems more real to us than real life. The more sports broadcasting technology advances, the more we become accustomed to seeing real-life events repackaged to us in strikingly unrealistic ways. Slow motion turns explosive bursts of speed into ballet, or breaks complex split-second plays down into easily identifiable component parts; digital overlays precisely compare the body positioning of a tennis player’s second serve to her first, or even to that of another player entirely, showing us the results on screen. Cameras trained on star players build an emotional narrative over the course of a game or season–like the powerful arc of Cristiano Ronaldo’s injury in the recent Euro 2016 final, his exit from the field in tears, and his subsequent spurring of Portugal to victory from the sidelines.

Sport is a perfect vehicle for hyperreality because we accept everything being depicted as real, and as a result disregard the standards of narrative and presentation we demand from other media. (Just think how we might feel about a feature film that was as slowly paced as a soccer game but compensated with liberal use of slow motion and 3D graphic overlays, or a director reproducing a sports broadcast shot for shot but with choreographed actors).

Crucially for this symbiosis with television and other media, sports teams and athletes produce a near endless stream of content, going far beyond their on-field performance to encompass photo shoots, interviews, social media accounts, brand endorsements, and more. Today’s sports stars aren’t just physical competitors, they’re (trans)media entities; and their teams are not only training and playing units, but production houses, too.

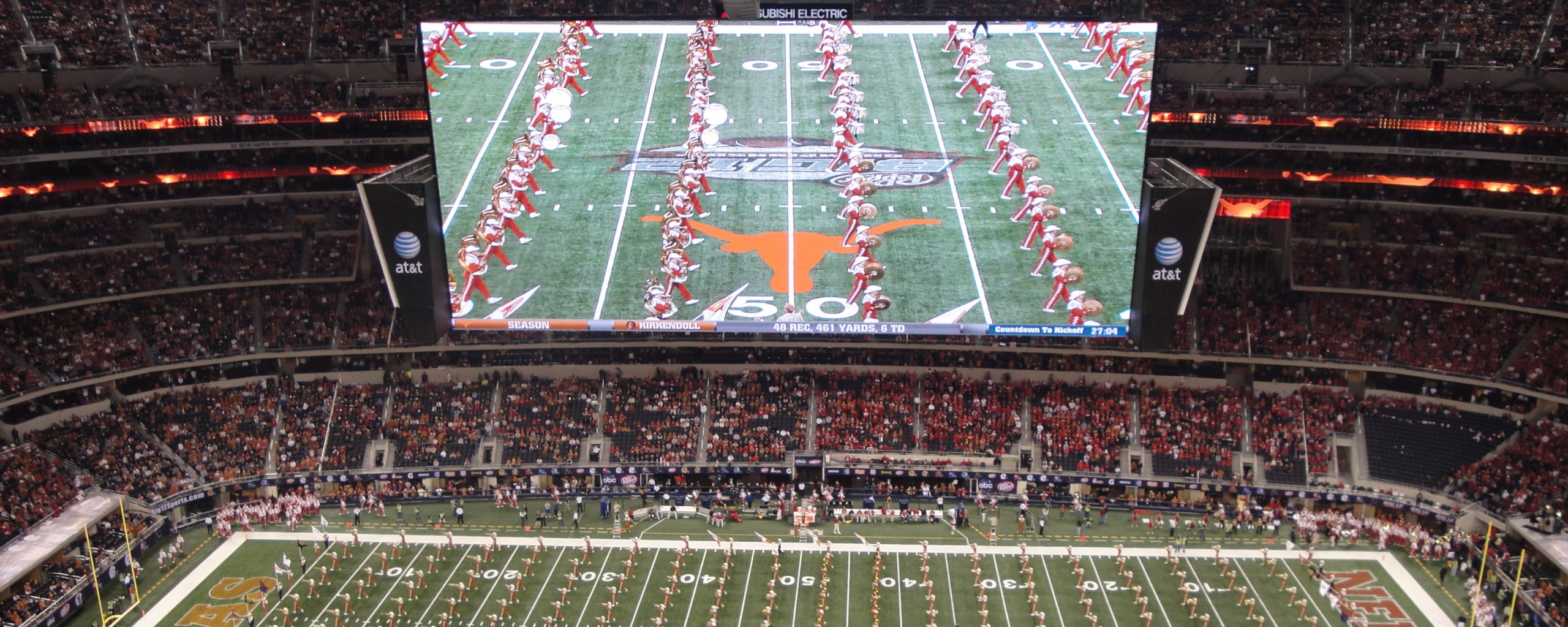

To this end, even stadiums now explicitly cater to fans bringing mobile devices and expecting to see additional content on them during the game. At the bleeding edge, the Sacramento Kings stadium, still under construction but slated to be the most high-tech sports arena ever built when it opens this year, will have an integrated app that guides you through every part of the game experience–from buying tickets, to parking, to finding seats, to viewing replays and stats during the live event. Just being there, it seems, is no longer enough.

Rather than just talk in abstractions, let’s look at how this marriage of sports, media, and commerce plays out in one city. Being based in Montreal, the closest place to me with a strong enough sporting presence is Toronto (sorry, Canadiens fans, but that’s just how it is). It’s large in size but not gigantic, and produces teams which are generally neither terrible nor hugely successful, but nonetheless significant. In other words, it’s an arbitrary choice but just about middling enough to work as a case study for an average sporting city in North America.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of sports teams based in the city, from largest to smallest fan base:

- Toronto Raptors (NBA)

- Toronto Blue Jays (MLB)

- Toronto Maple Leafs (NHL)

- Toronto FC (MLS)

- Toronto Argonauts (Canadian Football League)

- Toronto Rock (National Lacrosse League)

Of these teams, the Raptors, Maple Leafs, and Toronto FC all have official mobile apps. The Blue Jays app is an unofficial product, as is that of Toronto Rock, while the Argonauts have no dedicated app but are featured within the official one of the Canadian Football League. In addition, all of the above teams have a website–the first three (largest) teams operating as a subdomain of their main league URL (e.g., mapleleafs.nhl.com), the latter three as standalone sites. All teams except the Blue Jays run a dedicated YouTube channel: The Maple Leafs have the highest number of video uploads–an impressive 4,270–but the Raptors have over 10,000 more subscribers. All have official Twitter accounts, with the Blue Jays dominating at 1.46 million followers; on Instagram the Raptors lead with 810,000, but even Toronto FC manages a solid 74,000, with Argonauts and Rock at 24,000 and 11,000, respectively.

All of which is to say that a fan of just one of these teams would be able to consume a huge amount of content across multiple platforms, not to mention that most sports fans will have an affiliation for their city’s home team across multiple sports.

Above is a screenshot of the apps from each Toronto team with an official app, as listed in the Google Play store. Notice that all of the apps are made by the same developer, MLSE. That’s because all of these teams are owned by Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment Ltd, the largest sports entertainment company in Canada. MLSE not only owns the teams, but also own the Air Canada Centre in which the Raptors and Maple Leafs play, and manages the BMO Field, home to Toronto FC and, as of 2016, the Toronto Argonauts CFL team.

Here’s where it gets even more interesting. The largest shareholders of MLSE are Rogers and Bell, Canada’s two largest telecom providers, each of which bought a 37.5 percent stake in the company in a simultaneous deal in 2011; correspondingly, three quarters of the board of directors now comes from one of the two telcos.

So, here is (very literally) the billion-dollar question: Why is owning sports teams and stadiums so important to these two competing telcos? The answer, wrote journalist Jeff Beer in Canadian Business at the time, “could have been summed up in a headline, with three words written in all caps and 5,678-point type: “CONTENT! CONTENT! CONTENT! “¦ “

“¦ But that explanation only gets you partway to understanding the Bell-Rogers pact. Content is key, yes, but you don’t pay that kind of money and get into bed with a hated nemesis for just any content. What merits this kind of truce is live content with a best-before date, stuff like hockey games and soccer matches that fans can’t wait to see. And sports is the king of live content, not only for TV, but web and mobile video as well. [“¦] Sports is one of the last and most valuable vestiges of appointment viewing.

And there it is: The more our media landscape becomes fragmented, the greater the power of the authentic, live event, and the more valuable sports entertainment becomes. In the era of Netflix’s all-in-one series releases, sports are the last bastions of content that must be enjoyed according to a predetermined schedule. Own the rights to a sports team’s content and you can be sure of a regular, recurring base level of demand for it each week for the duration of every playing season, regardless of how your audience is split across channels and devices. Own the channels as well and you have a self-reinforcing cycle of revenue creation.

And all of this in a city with only mid-tier teams.

Toronto’s sports teams–like all major sports teams–are hyperreal, and in the most marketable way. As we move into a century in which natural resources start to approach physical (and climatic) limits, consumption of material products will be increasingly displaced by consumption of experiences, and the cultural and entertainment industries will gain even more importance as an economic force. During this period, sports franchises, with their consistent ability to create both content and revenue, will only gain in stature.

So here’s the prediction: Sports entertainment will be, and perhaps already is, the most valuable media content of the 21st century. It will continue to transcend platforms–television, streaming video, VR, augmented reality, and other forms yet to be invented–because, and not in spite of, the necessity of being anchored to a certain time, place, and structure.

But it will also remain popular because however little sporting performance resembles our own everyday lives, however superhuman the athletes become, we are still prone to recognizing something of ourselves, and of the great human dramas, played out on the field each week.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Playing the Field section, which examines how innovations in sports affect the wider world. Click the logo to read more.