In 1998, Boris Yeltsin had a problem with debt. He followed the advice of so many lawyers who advertise on late-night television and declared bankruptcy, nearly destroying the world’s financial markets in the process.

Yeltsin was the president of Russia at the time. Like someone stuck with an ex-spouse’s credit card bills, he decided that continuing to pay off debt that had been accumulated under the government of the old Soviet Union would be too damaging to the national economy. The Russian people needed to get on with their lives, and paying down the debt of a government they had rejected wasn’t going to help find closure.

National debt is simply the money that governments borrow to finance their operations. As with any loan, it can be used wisely or carelessly. In the same way that individuals can take out a mortgage to buy a house or charge up a credit card on designer clothes, a government might borrow money to build roads–or build outrageously expensive monuments to honor its supreme leader. When the projects are long-term, the government usually sells bonds to finance them, which is one reason some “debt investments” (or bonds) have maturities of 20 or 30 years. Believe it or not, governments have even issued perpetual bonds. In theory, the amount borrowed under a perpetuity need never be paid back, as long as the bond-holders receive regular interest. That’s right–the British government borrowed money in the 18th century it has never paid back.

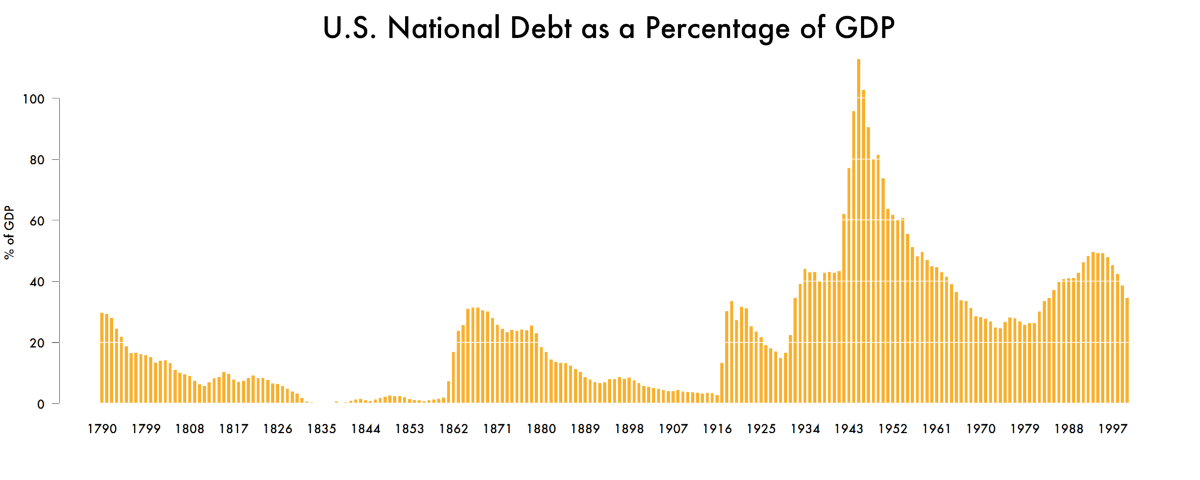

Many countries have been borrowing large amounts of money practically forever. The United States has had national debt since 1790, excluding borrowings to finance the Revolutionary War. The Bank of England has information on British government borrowings that date back to 1694.

In this century, the Bank for International Settlements reports that total government debt stands at $19.6 trillion, with $11.0 trillion of that belonging to the U.S. government as of the end of 2014.

Sure, that U.S. debt level may seem alarming, but the borrowers aren’t worried. Wealthy people all over the world still want to invest in the United States–because it’s a safe investment. Over half of the outstanding U.S. government bonds are held by people outside of the United States. The top five foreign holders of Treasury accounts? Mainland China, Japan, banking centers in the Caribbean, a collective of oil-exporting countries including Saudi Arabia and Iran, and Brazil.

China and Brazil are developing countries whose economies come with a lot of risk, and U.S. government bonds offer a way to keep money safe. As with an FDIC-insured bank savings account, the interest rate of bonds is low, but so is the risk. While it’s unclear who all has money in those Caribbean banking accounts, the account owners are probably rich people who have a similar interest in keeping at least some of their holdings very safe. Global oil trade is priced in dollars, so people in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, and other oil-producing countries have dollars to invest–putting them into U.S. Treasurys allows oil barons to keep their savings in the same currency as their income.

And Japan? The reason there are so many Japanese investors in U.S. securities is that the United States is as safe a place as Japan, but our interest rates are higher.

Yes, even at a current one-year interest rate of 0.68 percent, U.S. government bonds pay more than Japanese government bonds do. With interest rates this low, we shouldn’t be surprised that our politicians prefer to sell bonds (borrow money) rather than increase taxes or cut spending.

Interest rates are nothing more than the price of money, and the greater the risk that the borrower won’t repay the loan, the higher the rate. Certain wealthy nations with large, diversified economies are considered to have no risk. These prime borrowers include the United States, Canada, Japan, Singapore, and the like. Interest rates charged to these countries to borrow money cover the use of the money and expected inflation, but they don’t consider any repayment risk. Like any price, interest rates are determined by supply and demand. The supply of money from buyers of U.S. government bonds is so much greater than the U.S. government’s demand for money right now that bond buyers are willing to accept almost no interest.

Think of these rich investors as the salespeople at your favorite chain store, offering you a huge discount if you agree to take out a store credit card. When you do get the card, the store sends you discount coupons every month so you’ll borrow even more. Even if you pay off the card every month, you charge money the next month to keep the coupons coming.

That doesn’t mean that all government borrowing is good, nor does it mean that all governments are trustworthy borrowers. Governments have defaulted on their debt. Russia’s 1998 default was the most spectacular, but there have been others. Greece defaulted in 2015 but was eventually bailed out by the European Union, much like parents writing a check to help a wayward child.

Politicians hate to increase taxes or cut spending, so they often continue borrowing to support government activities. The situation in Greece was an extreme example of this truism. If a government can’t borrow more foreign money, its choices include doing those things that everyone hates: increasing taxes, cutting spending, printing more money, or declaring war on its creditors. Printing more money in small amounts is mildly inflationary. Doing it in large amounts leads to hyperinflation, which is devastating to an economy.

Greece’s problems were exacerbated because the country does not have its own currency. Unless the rest of the European Union agrees to it, it can’t print euros to solve its debt problem. Greece’s government could have opted for a return to the country’s old currency the drachma to pay off its debt, but that carries the risk of hyperinflation and greater economic problems.

The difference between someone who runs up a balance on a department store credit card to get discount coupons and someone who picks up the phone to call a bankruptcy lawyer advertising on basic cable between episodes of Seinfeld is more than the amount of debt in place. It is about the total amount of financial responsibility at stake. That makes sense, except that there’s not a lot of global agreement around the concept of responsible financial management. Think of your relatives at Thanksgiving, arguing about whether people should buy new cars or used ones, or about whether it’s better to pay off a mortgage or keep paying interest to maximize the tax deduction. There’s less love among politicians than in the most dysfunctional of families, making the discussion of debt really complicated.

The topic of how much debt is too much will continue to debated by pundits and academics forever, while voters try to make choices without clear guidance.

As for the Russians, Yeltsin’s default created new problems for the country, although it may have solved some others. It ultimately afforded Vladimir Putin the opportunity to undo some of Yeltsin’s moves toward democracy. Despite what the TV lawyers promise, bankruptcy is not an inconsequential solution. But maybe just enough debt is.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Made of Money section, which covers the future of cash, finance, economics, and trade. Click the logo to read more.