It was mid-morning, and Sitawa Wafula was working from home when she opened a troubling email. Inside, its writer spoke of the hours he’d spent submerged in the murkiest cesspools of the internet: those sites where the exhausted and desperate search for a way to end their lives according to one category or another–whether it be ease, time, pain, or visual impact.

Wafula was alarmed; had she received the message in time? She read on to find that somehow in his search the man had stumbled across an entry she had written about suicide on her personal blog. Its message had been about hope, about carrying on. “You know what, I’ll wait,” the man wrote.

“He said that he’d wait until the morning and he’d email me,” Wafula recalled. “If I replied to him, then he [said he would] have a reason to live.”

Sitawa Wafula is 31 and lives in the town of Ngong, a stone’s throw from Kenya’s capital, Nairobi. Her hobbies include writing poetry, reading, journaling, and wrapping twine around glass bottles, which she finds therapeutic. Wafula has been diagnosed with both epilepsy and bipolar disorder, and is a survivor of sexual assault. She also leads one of the most innovative mental health charities in Sub-Saharan Africa.

A mental health information and support hub, My Mind My Funk is part of a small constellation of organizations working in one of the harshest environments worldwide when it comes to mental health care provision. Its home? The internet–a place that most people in the country can reach. Last year, internet penetration in Kenya reached 22.3 million users, or 54.8 percent of the population. With that has come a newfound intellectual curiosity among ordinary citizens, not least of which includes challenging longstanding orthodoxies on mental health.

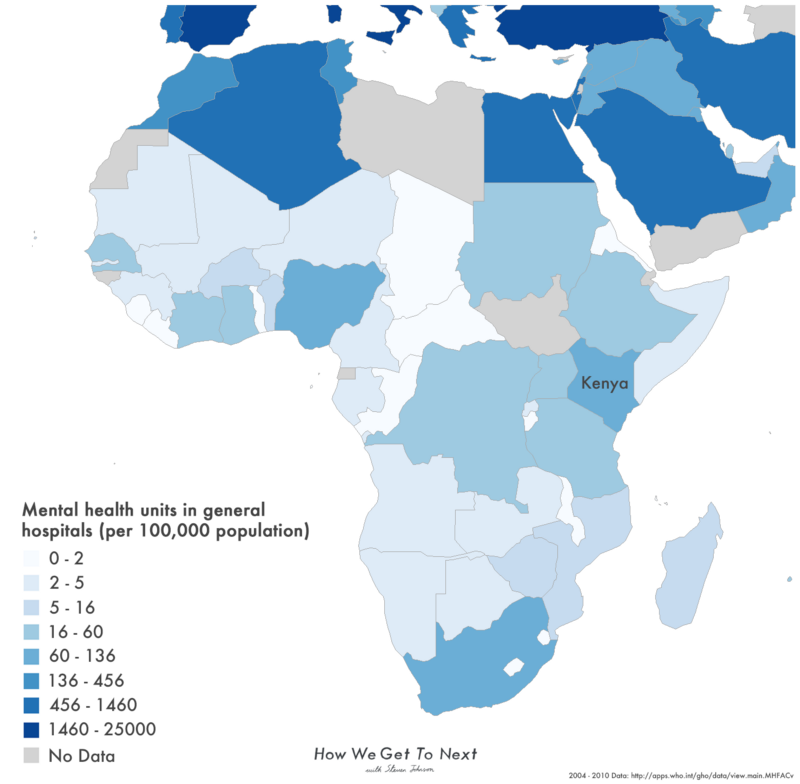

Kenya’s Health Ministry estimates that one out of every four people in the country lives with a mental health condition–usually undiagnosed. Overall, the country has fewer than 90 practicing psychiatrists, based mostly in the urban sprawl of Mombasa and Nairobi. That means the ratio of psychiatrists to patients is about one to 500,000, relatively good for Sub-Saharan Africa–and better by half than other developing countries like Nigeria where the typical estimate is about one for every one million people. Meanwhile in Zimbabwe only 12 psychiatrists serve a population of 15.3 million. Good mental health care can be tough to access even in Western countries; but for comparison’s sake, in the United Kingdom the ratio sits around 1:13,000.

What large-scale facilities do exist in Kenya have been repeatedly criticized in the past for poor levels of patient care. In May 2013, 40 patients rioted and then fled Mathari Hospital, the location of Kenya’s largest mental health care and only psychiatric referral facility, after several complaints about the institution’s inhumane conditions. Two years previously, a CNN documentary film crew obtained footage at the hospital of a mentally ill patient sharing a cell with a corpse, after which a number of human rights groups publicly accused the government of violating a U.N. convention on the treatment of disabled people.

This past April in Washington, D.C., the World Bank and the World Health Organization brought together a group of international doctors, aid workers, and government officials in an effort to push global mental health to the forefront of the world’s development agenda. “The situation with mental health today is like H.I.V.-AIDS two decades ago,” said Tim Evans, the World Bank Group’s senior director of health, nutrition, and population, at the time. “We are kick-starting a similar movement for mental health, putting it squarely on the global agenda.”

Then again, many Kenyans simply do not see the country’s beleaguered mental health care system as their first port of call. Kenya is typical of developing countries like Tanzania, India, and Nigeria where faith healing is viewed as an integral component of health care systems that, for centuries, have been squarely based in the local community. In that sense, mental illness is often indistinguishable from any other spiritual malady.

Then again, many Kenyans simply do not see the country’s beleaguered mental health care system as their first port of call. Kenya is typical of developing countries like Tanzania, India, and Nigeria where faith healing is viewed as an integral component of health care systems that, for centuries, have been squarely based in the local community. In that sense, mental illness is often indistinguishable from any other spiritual malady.

“If I speak to a generation like my parent’s generation, the information they had on mental health was the fact that it was a taboo,” said Wafula. “It [is either] a curse from God, or it’s a result of witchcraft. That’s the attitude that has been passed from generation to generation.” Treatments for those who have consulted faith healers can include being beaten over the head, enduring the placement of hot objects on the skin, and whippings. Others without any treatment at all can find themselves caged or tied up by family members to keep them from hurting themselves or others.

Thanks to the spread of the internet, however, that is starting to change. Access to information and sites like Wafula’s have raised awareness nationally about the signs and symptoms of everything from depression to schizophrenia. Still, this has not been enough to banish the societal stigma that comes with seeking assistance.

“People don’t want to talk about it openly,” explained Wafula. “It’s not necessarily something that people are very open to start discussion about, but the good thing is that they’re open to seek help.”

Wafula, of course, has experienced both sides of that process. At a young age, she was diagnosed with epilepsy. When she was 18, she was raped. In both cases, her parents did not fully understand how to support their daughter and her condition–so she searched for an account of someone who would.

“I wanted to read someone’s story and know that they were alright, that regardless of what had happened to them, that they’d lived for so many other years and they’d been able to go on with their lives,” she said. “And I never read any story like that.”

So, Wafula wrote her own. In 2010, she started a blog that documented her daily thoughts on her mental well-being. She called it a “Diary of Africa’s Mental Health Super Hero,” and it continues to this day.

“I didn’t have all the answers for what I was going through when I began,” she said. “I didn’t have all the answers for living with epilepsy. I didn’t have all the answers for living with bipolar, when I was eventually diagnosed with it. But I knew if I had read someone’s story and knew that I was not alone, that would be enough for me to live through that day. And so I wanted to give what I had not gotten to someone else.”

As the posts accumulated, Wafula started to receive emails from readers. She rarely, however, received public comments on her blog, something that she sees as unsurprising given the widespread reluctance of Kenyans to discuss mental health issues openly. Despite this, her work to raise awareness around mental health soon attracted the attention of NGOs and other organizations based outside of Africa. In 2014, she was awarded $25,000 as a finalist in Google’s Africa Connected competition and used the money to start My Mind My Funk.

Since then, Wafula and her colleagues have assembled a referral network of psychiatrists across Kenya; liaised extensively with county health authorities to raise awareness of mental health conditions and enhance standards of care; and via an open letter on Wafula’s blog forced one of Kenya’s premier tabloids, The Star, to retract a headline that labeled a doctor with a history of paranoid schizophrenia as “mad.“

The result has been an organization that defines success more like a tech startup than a charity: While MMMF gratefully accepts donations and embarks on awareness drives up and down the country, its ultimate focus is on aggressively narrowing the enormous gap between demand for mental health care and actual provision in a results-based, practical fashion.

“For me, it’s how quickly can someone who’s suicidal be able to get whatever support they need, how quickly someone who’s asking me to give them information about someone else who’s having a seizure is getting that advice,” said Wafula.

“And it’s getting that information right now, and not being directed to another website or being told to call us during these set hours.”

MMMF’s latest component–an SMS helpline–is the clearest distillation of this goal. Now, anyone who is worried about the impact of a mental condition upon their well-being, or that of a friend or family member, can text the details of the situation to 22214 (users only need the most basic type of phone to text in). The most serious cases see the person called back by one of the charity’s advisors.

The insights gleaned so far from user demographics reveal that a slim majority of callers are men who find it difficult to talk, for example, to an advisor one-on-one; many are also reaching MMMF from the countryside, where support networks are thinly spread compared to urban areas.

Next, Wafula is considering pushing her work beyond Kenya. “I want to “¦ start getting more contacts [within] mental health service providers across Africa, because I’m getting a lot of inquiries–specific inquiries–like, “‘Do you know anyone I can see in Ghana?’ or “‘Do you know anyone I can see in Botswana?'”

For the moment, though, much of her work is still concentrated in connecting Kenyans with the mental health support they need. When asked about the moment she knew her work was starting to have an impact on her readers, Wafula reeled off stories of grandparents thanking her for lifting them from the fog of bewilderment they’d lived through for so many years; of girlfriends, boyfriends, wives, and husbands letting her know that their partner has moved from this stage of recovery to that one after subscribing to her blog.

And then there was that email she opened one morning at home, from a man new to her blog and desperate to be heard. In the end, Wafula did what she does for anyone who contacts her; she responded, offering support and referring the man to a psychiatrist in her network. They remain friends to this day.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Vital Signs section, on the future of human health. Click the logo to read more.