The first humans who will live to 150, or 200, or 1,000, or forever are already alive. That’s what we’re told with increasing regularity as we look down at our bodies and regretfully conclude that we might not be the ones in these categories.

Why we age is still a matter of some scientific debate, but it basically boils down to one factor–life. Throughout our lives, for all kinds of reasons, we continuously accumulate damage in our cells. Eventually, that damage kills us–at a rate of about 150,000 people per day, at the time of writing.

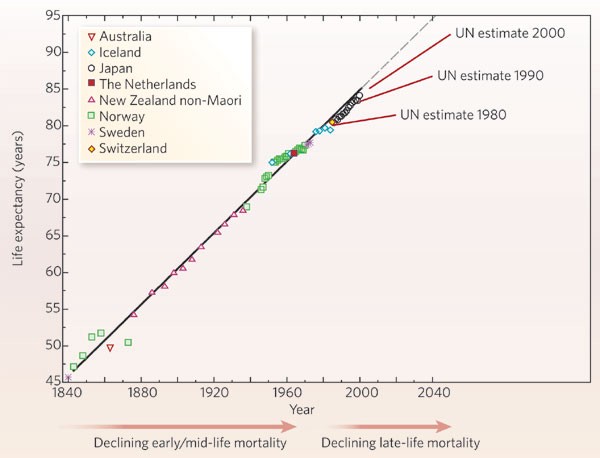

But there are a bunch of ways we’ve intervened in the ancient process of aging. Tool-making was probably the first, around 2.6 million years ago, followed by control of fire, writing, trade, agriculture, logic, the scientific method, the Industrial Revolution, democracy, and so on. Each one of those advances, and many more, progressively expanded our life expectancy–particularly over the last 200 years. Today, human lifespan is lengthening at a rate of about two years per decade.

The rate at which we age stays constant and, historically, so does the rate at which life expectancy increases. If we could accelerate the latter rate*, the two would eventually meet. What happens when the rate at which life expectancy increases exceeds the rate at which we age? We become immortal, that’s what.

It might not be so noticeable at first. The initial breakthrough could be an extension of healthy life by, say, 20 years. That buys us 20 years to gain another 20 years, and so on. If the development of life-extension research follows the same trajectory as other advances like medical care or computing, then anti-aging therapies will improve faster than the remaining imperfections in those therapies catch up with us. Futurist and biomedical gerontologist Aubrey de Grey calls this point “longevity escape velocity.” It’s the point at which the human population will cleave in two–the people who will die, and the people who won’t.

This is where all kinds of interesting questions start to crop up. How will those two populations treat each other? What will immortality mean for institutions like employment and marriage? Will children become as rare as hundred-year-olds are today? But let’s focus on the most important question of all”¦

What’s for lunch?

There’s no doubt that being immortal is going to change how we act as a species. “I think that people will be less inclined to take risks,” said de Grey in a recent interview with Gigaom. As well as a marked decrease in motorcycle ownership, smoking, and hanging out around snakes, that also means being less risky with what we eat, because food contributes hugely to lifespan.

A brief Google search for “anti-aging diet” brings up zillions of sites with questionable advice on what to eat to avoid inflammation or wrinkles. If you ask a scientist, however, the advice is a lot more simple–”calorie restriction,” or eating less.

It turns out mice that eat 15 percent less starting at a young age add a significant amount of time to their lifespan–the equivalent of almost five years in humans. That’s mice of course, but preliminary studies on calorie restriction in primates and humans show that the results should apply to us, too. “There is absolutely no reason to think it won’t work,” said Eric Ravussin, who studies human health and performance at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Louisiana.

De Gray is a little more skeptical about calorie restriction but broadly approves. “I think that CR will probably give humans only 2″”3 years of extra lifespan at most,” he wrote in 2005. “But the health benefits are clear, as shown in the Holloszy and Fontana work, and even 2″”3 years may make a big difference to quite a lot of people.”

So the first immortals are likely to eat small portions. But of what? For the best guide, perhaps we should look at the places in the world where people live the longest and healthiest today. These areas are scattered from Greece to Japan; demographers Gianni Pes and Michel Poulain, who studied the longevity of Sardinians in 2004, named them “Blue Zones.”

Today, the Blue Zones label is associated more with writer and explorer Dan Buettner, who penned a cover story for National Geographic in November 2005–identifying five regions where people live significantly longer. He wrote:

People in these regions, the researchers found, live as much as a decade longer than their counterparts elsewhere, produce several times more centenarians, suffer a fraction of the diseases the kill most Americans, and enjoy more good years of life than anyone else on the planet. In essence, they offer “best practices” for the rest of us to emulate.

Buettner has since written much more on the topic and turned the Blue Zones concept into a profitable brand that he tours across the United States, including a 2009 TED talk. It’s only tangentially science-based, and certainly not peer-reviewed, but the dietary components of the Blue Zones lifestyle he recommends are at least evidence-based–they include a plant-centric diet with little meat, moderate alcohol intake, and frequent consumption of legumes like beans and lentils.

In guessing what the first immortals will eat, we can’t just look at what’s best to eat. We also need to account for what’s going to be available to consume in several decades’ time. Meat and dairy will likely be off the menu–at least in their current state. (Fish might well be too, depending on how we regulate fisheries in the coming years.) The countries of the world have agreed to limit climate change to just two degrees, and livestock farming is one of the major contributors to global emissions. The burgers of 2050 may or may not be lab-grown, but either way they’re expected to be delicacies consumed on occasion–not at every meal.

Vegetables are likely to stick around, but climate warming means we’ll be consuming more of the species that thrive in hotter temperatures and fewer of those that don’t tolerate heat well. Corn, cucumbers, melons, peppers, tomatoes, and squash are all likely to become more popular; meanwhile leafy crops like lettuce, cabbage, and spinach–as well as leeks, peas, carrots, and onions–may become less common.

In April 2014, the British Food Climate Research Network published a report on sustainable, healthy diets. A set of guideline principles (on page 30) recommend that people eat more plant-based foods; moderate meat consumption; drink tap water; and avoid fat, sugar, and salt, but my favorite bit of advice in the list is point three. It reads: “Value your food. Ask about where it comes from and how it is produced. Don’t waste it.”

Finally, I asked biodemographer James Vaupel whether a generation of people who live significantly longer than their parents would choose to eat different things as a result of their longevity. “Interesting question and not one I have ever thought about,” he wrote back in an email. “Half or more of the generation born in rich countries after the year 2000 may celebrate their 100th birthdays if past trends continue. What will these people–including my three young grandsons–choose to eat? I would guess a healthy, balanced, diverse diet–because they will not want to risk not living to 100 and because they will be rich enough to afford it.”

So, given what we know, here’s what I imagine will be on the menu at the first restaurant catering to immortals wanting to keep their bodies in tip-top shape in 2050.

- Small portions. Calorie contents of meals will be labeled and monitored.

- Vegetables everywhere. They’re cheap, fresh, and packed with good stuff–but they might not be the same ones your parents ate.

- Loads of legumes. Beans, peas, and lentils have tons of protein and fiber, as well as a bunch of vitamins and minerals. They’re also super cheap.

- Very little farmed meat. There are better protein alternatives (including those legumes mentioned above, tofu, and other meat alternatives we’ll no doubt invent in the coming years) that also don’t contribute to antibiotic resistance, pollution, and climate change.

- Water and wine. The residents of most Blue Zone regions drink alcohol moderately and regularly, while tap water is the best choice for hydration.

* This “if” is obviously not a small one, but we’re working on it. Organizations like the Methuselah Foundation and de Gray’s Sens Research Foundation are directing funds toward scientific research about keeping people healthy for longer. There are also multiple prizes on offer for breakthroughs in the field. If you’d like to check out the current state of aging research, this recent BBC Future piece should prove illuminating.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our The Future of Food section, which covers new innovations changing everything from farming to cooking. Click the logo to read more.