Toward the end of the 19th century, Western medicine had an image problem. Joseph Lister’s ideas about antiseptics were spreading, and John Snow had made a breakthrough in mapping the spread of cholera. But to the public, most medical “cures” were little more than quackery and mysticism, and the appearance of a physician merely presaged a painful death.

At the same time, the reputation of science was in rapid ascendancy. The Industrial Revolution was transforming the towns and cities of Europe and America, and new breakthroughs were reported on a weekly basis in more than a thousand different scientific journals.

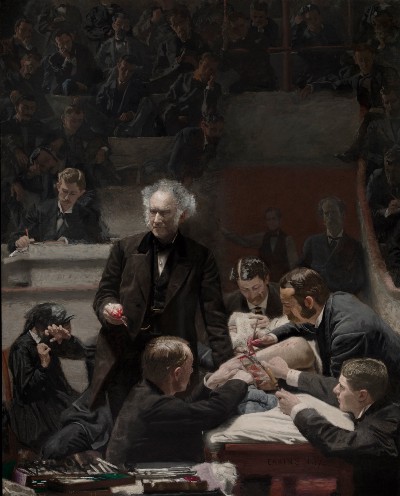

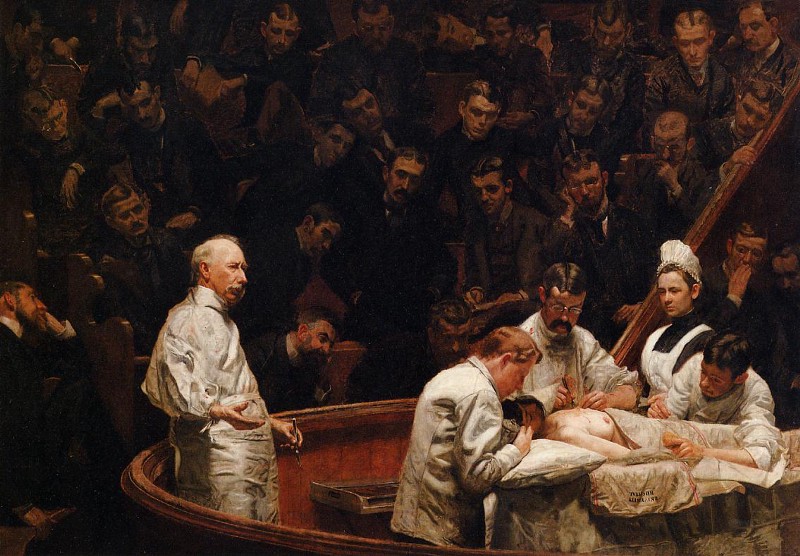

So the medical establishment did a costume change. Doctors dropped their traditional black coats, which were worn either as a mark of formality (like a tuxedo) or to symbolize the solemnity of their profession, and instead opted for white coats like the ones worn by scientists in their laboratories. The shift can be seen clearly in two different paintings by Thomas Eakins of operating theaters in the United States, separated by just 14 years.

The white coats symbolized more than just scientific rigor. They represented cleanliness, purity, and a fresh start for the medical profession. Over the next couple of decades, things changed rapidly. William Osler published his legendary 1892 textbook, The Principles and Practice of Medicine; and the 1910 Flexner Report, which called upon American medical schools to implement higher admission and graduation standards, reoriented medicine around laboratory science. Doctors, for the first time, gained real scientific authority.

Today, at many medical and veterinary schools in the United States, new students go through a “white coat ceremony” before they begin meeting patients. The ritual involves a formal “robing,” marking the student’s transition from preclinical to clinical health science–almost like the ordination of a priest. Since the first white coat ceremony was performed at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1993, the practice has spread to medical schools in Iran, Israel, Canada, Pakistan, the United Kingdom, Brazil, Jamaica, and many more.

But in hospitals the white coat is beginning to once again fade from view. Surgeons prefer blue or green scrubs, as under the bright lights of an operating room white coats strain the eye and lead to headaches. Psychiatrists like to keep their patients at ease, wearing a casual shirt and trousers or skirt, while pediatricians also tend to avoid the white coat for fear that kids will find it threatening. Studies have documented a phenomenon known as “white coat hypertension,” where patients exhibit higher blood pressure in a clinical setting. Some doctors even believe that white coats foster a “sense of entitlement.”

There’s also much debate over whether lab coats are a direct threat to patients themselves–some studies have shown them to harbor contagions like MRSA, while others note no statistical difference in contamination rates between long-sleeved lab coats and short-sleeved surgical scrubs. The British National Health Service banned the coats in 2007 before softening the rules again in 2012. Current NHS guidelines state:

“Where white coats are worn these are to be changed weekly as a minimum or when visibly contaminated. Good practice would not support the use of white coats in the clinical setting, however if used the sleeves need to be cropped to facilitate hand hygiene.”

In 2009, the American Medical Association mulled over a similar ban, eventually concluding after protest from doctors that more study was needed. (That study appears as though it’s still ongoing.) India also considered a ban in 2015, following the release of a study showing it could reduce the spread of infection, with no conclusion yet. In Spanish-speaking countries, white coats are a symbol of learning and worn as part of the daily uniform in many schools, medical or not.

The lab coat is far from dead, however. Outside of the medical world, it remains the uniform of choice for most laboratory work, and scientists are constantly tweaking and reworking the design.

Leslie Latterman is one of those who’ve improved substantially on the traditional lab coat, rebuilding it from scratch with women in mind. In 2014, after a long night shift during which she complained her lab coat was “dingy and heavy and it fit me like a tent,” she gathered together a group of women doctors to come up with a solution.

The result was the Signature Lab Coat. It adds several features that elevate it above the traditional design, from velcro epaulets that can securely store a stethoscope, to an internal wallet, roll-up sleeves, soft antibacterial fabric, and dedicated pockets for pagers, cellphones, instruments, and pens. Most importantly, it’s cut to fit a woman’s body, rather than a man’s.

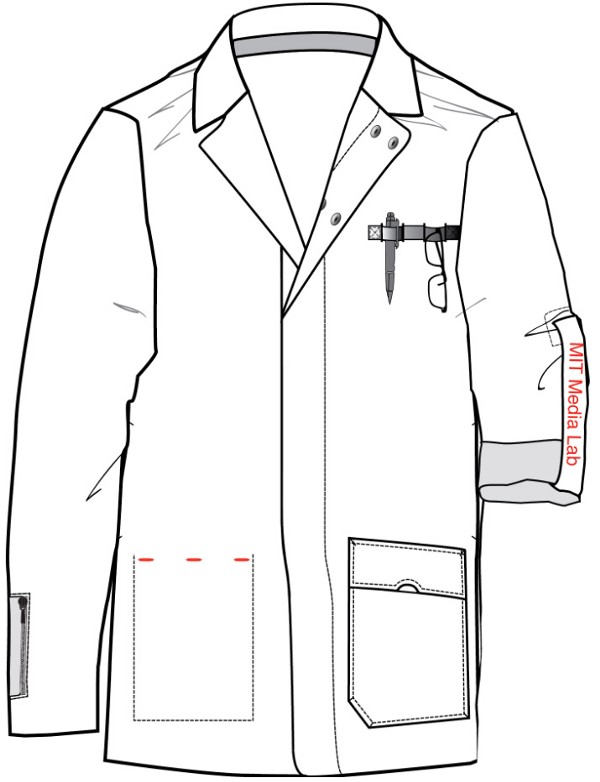

MIT’s Media Lab has also reworked the traditional lab coat into something more suitable. “Media Lab researchers are not only scientists–we are also designers, tinkerers, philosophers and artists,” wrote the group responsible for the redesign on a dedicated website. “We need a different coat!”

They set out to rethink the lab coat as a framework for customization. “It features reflective materials, new bonding techniques, and integrated electronics,” the team wrote. “Each Labber has different needs. Some require access to Arduinos, others need moulding materials, yet others carry around motors or smart tablets.” The group also plans to explore protective eye-wear, shoe-wear, and more in the future.

But for perhaps the most interesting glimpse at how the lab coat of the future could differ from today’s, we should turn to Gerhard Mohr–a textiles researcher at the Joanneum Research Institute in Austria. His team is developing textiles that change their color when exposed to toxic or dangerous substances.

You can imagine how useful that could be in a laboratory setting. “[Lab coats or work gloves] are being coated with dyes that respond to substances that could burn your hands or if carbon monoxide is in the air–a poisonous gas that you can neither smell nor taste,” he told Compamed Magazine in a 2014 interview.

“Other application areas include textile-based wound dressings in clinical diagnostics with which you can measure pH levels in wounds. You could color wound dressings with dye that for instance changes its color from green to red in case of increasing pH. This is therefore an immediate signaling effect: green means everything looks good; red means you need to act accordingly.”

The only hole in the history of the white lab coat is its origin. Scientists were clearly already wearing them in the late 19th century when the medical profession needed a new image, though some sources believe they were originally beige.

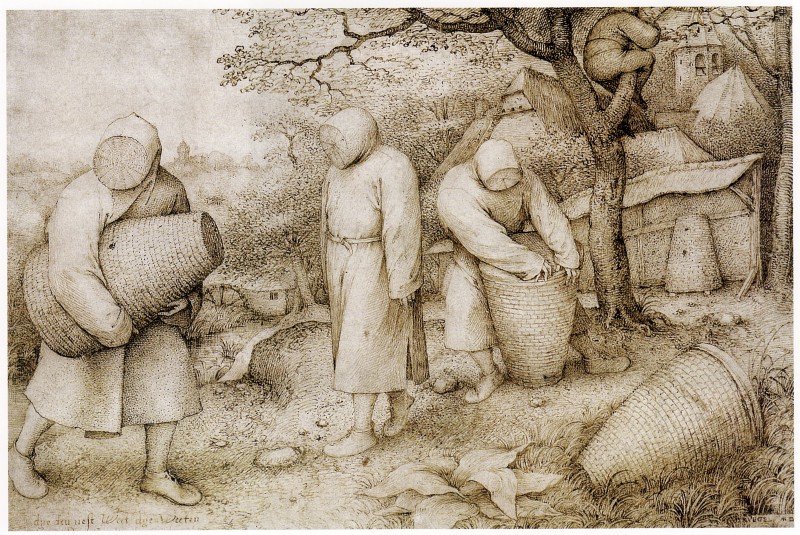

It’s likely the lab coat evolved over time from the protective equipment worn in many industrial professions to shield its wearer from harm. Blacksmiths in the Middle Ages wore protective aprons to keep from being burned by the molten metal they worked with, while beekeepers from the 1400s onward were known to make use of protective suits (as in the creepy painting above).

With scientists in similarly dangerous situations in their laboratories, it’s very likely that they followed suit to adopt similar tactics for protecting themselves. White or beige was probably the chosen color simply because it was the cheapest available fabric.

“As each of you walks across this stage today to receive your white coat, your journey in medicine will begin,” Bernard Karnath told the White Coat Ceremony at the University of Texas’ Medical School in 2011. “The white coat reminds physicians of their professional duties, as prescribed by Hippocrates, to lead their lives and practice their art in uprightness and honor. [“¦] Wash them often. Avoid pocket stains and consider having a spare coat available for that morning when you spill your coffee on your sleeve.”

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Sartorial section, which looks at the impact of science and technology on how we present ourselves to each other. Click the logo to read more.