In our modern age, we like to think that women can be and do anything. We tell our daughters it’s great to excel at math and science, to develop new technologies (like the kind that enables our smartphones), or even to captain a spacecraft.

But–and it’s a big but–is it really the best idea to frame improving women’s standing in the world of work as worth something only if it comes in fields where men are traditionally (and often, wrongly) considered to be more naturally adept?

At the moment, the most popular advice for young women is that they study for a career in STEM (science, technology, engineering, math)–which, these days, now also includes a demand that everyone learn to code. Since it’s men who currently and overwhelmingly pursue these associated career paths–men who are making decent salaries (the average Silicon Valley tech worker makes six figures), getting promoted, founding startups, and hiring lots of people–there’s some logic to encouraging others to follow their lead and charge headfirst into the fray.

A problem remains, though. Society still doesn’t, broadly speaking, encourage girls and young women to charge headfirst into anything.

By the time all these young women (and homeless people, and people of color, and anyone else who’s supposed to jump on this learn-to-code bandwagon) have actually learned to code, the work will be standardized, rote, and repetitive, as it was when women were hired in the early days of programming. Not surprisingly, pay scales will plummet as more women enter the field. By then, men will have moved on to something else entirely.

Maybe it’s time for women to move on to something else, too? Women shouldn’t be fighting for a place at work; they should be inventing, designing, prototyping, and coding a new ideal of work–something which isn’t based on an out-dated belief about gender roles in society.

Ever since the scions of the Industrial Revolution figured out that it was more profitable to hire women and children to work in textile mills because their hands were smaller and fit more easily into the machinery, women have worked harder, for longer hours, and been paid less for the privilege.

Until the Industrial Revolution, employment, or even the concept of a “job,” didn’t really exist. Entire families helped with agricultural production or worked in related trades, and this labor was mostly done without direct compensation, beyond keeping a family sheltered, fed, and clothed. Once populations began moving into cities in the 19th century to take up factory jobs, it became imperative for women to help support their families financially and find employment outside the home. Women joined the workforce.

At the same time, factory bosses realized the cost advantage of hiring women and children. This shift freed up working-class young men to attend public schools, continue into secondary education, enter professional-level employment, and accumulate wealth–all things previously accessible only to the landed gentry or the aristocracy. The middle class was born, though women, immigrants, and people of color were still relegated to lower status, with few legal rights and little independence.

As work became routinized through the Industrial, Service, and now our current Digital Revolution, one pattern has remained constant: New types of work–especially creative, innovative, scientific, or any field seen as emerging or multi-faceted–is encoded as male. When these roles become standardized, commodified, and more uniform–factory work, teaching, secretarial or administrative work, librarianship, and nursing come to mind–employers have turned to women to fill these positions en masse. Women’s work is what remains when jobs become systematized, with little likelihood of further alteration, innovation, or disruption.

In most cases, as work becomes predictable and unvarying, there is no longer a clear path of advancement. Despite some progress in limited areas, women have remained firmly entrenched in a pink-collar ghetto, meaning that in our current economy they are more likely to work as “non-technicals.” Even within the tech industry, women are most often found in less visible, lower-paid marketing, project management, or human resources positions. By definition, these are not starring roles in company hierarchies and tend to be fire-walled in terms of promotion opportunities.

Women who do break the barriers of entry into male-dominated fields continue to struggle for acceptance, or to get credit for their successes, and they are often publicly ridiculed for any failures–even those which do eventually lead to breakthroughs and progress. A recent study by social psychologists Kristen C. Elmore and Myra Luna-Luceroy found that public perceptions of creative insight or technological advancement are viewed differently depending on the gender of the inventor. People will credit a man’s ideas as being exceptional or brilliant if they are described as coming on suddenly, “like a light bulb,” while preferring to talk about women as passively “nurturing” an idea, “like a seed.”

History is full of women who have failed to receive full credit for their groundbreaking innovations and ideas. Popular culture continually reinforces our perceptions of women at work as well. When researching this piece, I looked for film images of women teachers, but despite the fact that over 70 percent of all teachers in the real world are women, most biographical films about teachers feature men in the lead or title role.

Our collective impression of women in the workplace continues to be framed through a limited lens of a traditional, conventional woman who is, in some way, an uncharacteristically clever female role model.

Katherine Johnson began working as a physicist for NASA’s predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), in the 1950s–a time when taking a government or civil service job was often the only option available for women, particularly women of color. That Johnson and her colleagues could never have been hired at Lockheed Martin, Boeing, or McDonnell Douglas in the 1960s is reminiscent of the high-tech economy today. Gender and race diversity in founding roles at most Silicon Valley startups remains highly skewed to favor white and Asian men under 30.

Even today, most public sector and government organizations hire women and minorities at significantly higher numbers than the private sector. This is because these organizations offer lots of job security, but with significantly lower salaries–something white men are less likely to pursue or accept.

While the public sector is shrinking, and despite efforts to downsize and streamline government agencies civil service will probably remain a reliable place of employment for many years to come. Innovation moves at a glacial pace within these organizations, so civil servants are challenged–they have fewer opportunities to innovate, or to initiate change within a bureaucracy. Public sector workers can struggle to keep their skills aligned with the expectations of the open market, where it’s becoming increasingly common that their jobs are no longer performed by human workers at all.

Madeline Ashby, a strategic foresight consultant and novelist, suggests that “one of the reasons women are socialized to choose ‘sustainable’ jobs (like teaching, nursing, even programming “¦ computing, or project management, etc.) is because we don’t teach girls risk.” Because women are taught from birth to be risk-averse, they approach work with a different mindset–one which values exactness, tight deadlines, and perfection of finish over experimentation and rough prototyping. Ashby says, “We punish girls for failure in a different way than we do boys; boys are meant to “‘fail faster’ so that they can learn, whereas girls are expected to do things perfectly the first time around.”

There is no doubt that women have changed the landscape of the workforce in the last two centuries, and more and more women are working in fields formerly regarded as only for men–jobs like doctor, scientist, architect, soldier, CEO, and possibly even President of the United States. But for a majority, the usual path is still one of working harder, and being smarter (and more highly educated) than the guys, with little chance of ever making (or getting credit for) breakthrough discoveries, or creating inventive and useful technologies. In other words, the things that get the most funding, and which attract the most fame and praise.

Even today it’s not hard to see that women in corporate employment continue to hit the glass ceiling. It’s still quite rare for women to become top executives, unless of course a company (or political party) finds itself in dire straits, or is charged with legal or ethical violations. In those cases, with the chances of success seen as low and the reward not worth the risk, it’s become de rigueur to promote a woman to the top spot. It’s so expected that there’s even a name for it: the glass cliff.

Studies confirm that as women get closer to the age of 30, their opportunities for advancement and increasing financial rewards start to level off. This is also a time, not coincidentally, when most organizations assume a woman will be considering major life changes not related to her career–things like marriage, or having and raising children. It’s possible to argue that most women are paid less because their time is valued with prejudice, probably out of the expectation that they have to be responsible for housework and child-rearing. (I could write an entire piece considering why we call mothers with jobs “working moms” but no one ever calls a father a “working dad.”)

But, could it also be possible that the underlying reason for the wage gap is that there’s a pervasive bias that women are only suited for work that is safe, disciplined, orderly, and time-constrained? And that, therefore, they’re not the preferred candidates for creating, exploring, and leading–even when they excel at those skills?

The prospect of menial jobs being replaced by robots, leading to mass unemployment, is not a new one. There’s also an unsettling assumption that women have a passion for education and careers for only as long as they “need” to work–and that a data-driven algorithm is the only thing a smart company needs to satisfy consumers on a global scale.

It seems likely that more and more performative labor–the modern day piece work of our gig-economy–will fall to our increasingly capable virtual and digital assistants. It’s telling that so many of these devices and apps have feminine names–Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, Microsoft’s Cortana, and Google Now’s Amy. Their function is to take on the rote tasks of day-to-day life, without comment or complaint. Their skills are not just coded, but encoded–as female. There is an underlying assumption by the creators of these devices that the work they are programmed to do is gendered female, because they work in service to us.

These static containers can understand voice commands but do not have agency, and they do not act unless told to do so. It’s worth pointing out here that IBM’s Watson, and the disturbingly sentient HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey, have masculine voices and names, and are described as having superior problem-solving skills and intellect to humans.

Jamais Cascio, a futurist and author, believes that human jobs of the future will require empathy and human contact, two things that (for now) robots, machine learning AIs, and algorithms can’t do very well. Not coincidentally, these two things are also most often seen as a requirement for women and the types of work they do. While we’re often being persuaded that robots will replace blue-collar workers, there’s a mistaken assumption that high-functioning jobs that are typically seen as male can’t (or won’t) be replaced with non-human workers. It’s happening already. Think about that for a minute: Would you rather have an AI as your financial advisor, or your home health nurse?

Cascio argues that once automation begins to replace work that is easily programmable–financial, surgical, manufacturing, transportation, the list is virtually endless–then jobs with a caretaker component, which require a certain level of emotional intelligence, may be the only professions which can never fully be replaced by non-human workers. This might be very good news for some women, but it could also signal a regressive demand for affective labor, and frankly these are not the types of careers young, college-bound women are being directed toward.

In other words: We shouldn’t be teaching women to code in a world where those skills are going to become less valuable over time, only to allow men to move on to more creative work that women might have an equal affinity for doing. Instead, we should focus on encouraging women to invest in, and nurture their own proficiencies for innovation, creative thinking, design and empathy.

Before the new Ghostbusters was even released, there was a well-publicized uproar over the gender-reversal of the original “classic,” the second-highest grossing film of 1984. How could women be funny in those roles? How could Paul Feig, the director, dare to make this movie with women as the leads?

There was a distinct divide between how men and women reviewed the film, and the backlash against Feig and the cast was even more strangely over-the-top if one considers that the original was little more than a live-action cartoon of immature men doing a job that doesn’t actually exist (plus a few now cringe-inducing, implied sexual assaults and a giant marshmallow man destroying skyscrapers). The new film didn’t do well at the box office, but we’ll never know if that’s because it truly isn’t that good or funny, or if a bunch of men decided they would reject the entire premise because it was too outrageous to consider the possibility of women busting ghosts.

Is this where we are now? Women aren’t even allowed to pretend to do a (fake) job in a movie, because it’s somehow inconceivable that they could do (fake) work as well as men did it in the past?

It’s entirely possible that in the future there will be no jobs. We could easily find ourselves living in an age where human beings are only invited to labor if and when we want. We are fast approaching a time when our new and developing technologies are much more capable of doing our work than we are.

It might seem impossible for any of us living today to imagine that we could feel comfortable with the idea that our self-worth might at some point be determined not by our skills, talent, and work ethic, but instead our ability to empathize, embrace, and connect with another human. These are qualities which machines can sometimes mimic but struggle to portray authentically. Could this be the shift that helps to change the artificial boundary between men and women’s work?

Zan Chandler, a foresight analyst, offers a similar perspective: “The way the world operates is set up to perpetuate structures in service of men. White, able-bodied men in particular. Anyone else is at a disadvantage. That isn’t to say individual “‘others’ can’t succeed (or get ahead) in the system–but, power rests and seems to want to stay flowing in these systems, in ways that perpetuate the way the systems run now. Small changes here and there aren’t enough to break the system down and reform a new one.”

It seems clear that our Digital Revolution is ripe for an opportunity to break from the framework passed down to us from the Industrial Revolution–a framework that has segregated and diminished opportunities for women for almost two centuries. Could this Digital Revolution prove the catalyst we need to start imagining new futures for women, instead of pushing us to compete for places in the existing system, just as it might be falling apart?

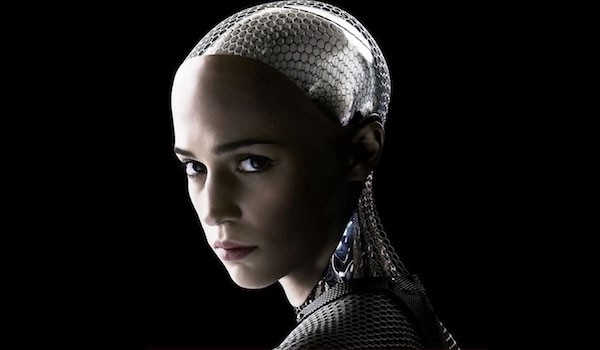

One clear break from the past must be that our non-human workers be non-gendered as well. If we continue to define machines and devices as “male” or “female,” relative to the work they do for us, we perpetuate the myth that women’s work is lesser than men’s. Ava, the female-encoded, sentient AI in Ex Machina, has no better prospects than Doralee, the boss’s secretary in the Dolly Parton movie 9 to 5; they both try to beat the system at its own game, but end up realizing they’re better off breaking out of it altogether.

From a pop culture perspective, it feels like nothing has changed. Maybe shaping our future is a job that’s better suited to women.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our Identity section, which looks at how new technologies influence how we understand ourselves. Click the logo to read more.