It’s a big deal that Jason Walker earned his GED at age 36. Where he studied for the test–behind bars–the teachers aren’t required to have educational credentials and not all have passed America’s high school equivalency test themselves.

After eight years in a Texas state prison, in Walker’s experience learning has been disruptive and fragmented. Along with security lockdowns and facility transfers, he says even trained teachers aren’t effective “because most get intimidated by prisoners and out of fear let them do whatever they want.”

What Walker wanted to do, though, was learn. So he persevered, first with a long waiting list to get into the classroom, then in classes interrupted by unmotivated students and months of delays due to insufficient staffing. Passing the GED, a test that was overhauled, computerized, and reissued in 2014 with a success rate of just 16 percent the previous year’s figure, meant access to college courses and vocational training.

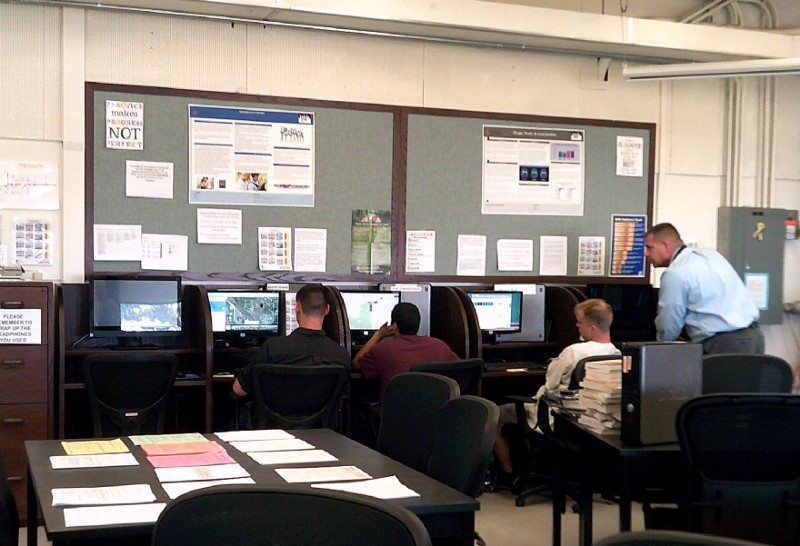

The latest data shows that only 22 percent of Americans in prison have ever used a computer. This gap in computing basics is just one of many obstacles to reintegration into modern society upon their release. That’s why among both prisoners and forward-thinking administrators there’s an appetite for increased access to digital education resources, in an attempt to address the mismatch between what’s being taught on the inside and what’s relevant on the outside. Viable jobs upon Walker’s release will depend on familiarity with technology, not just for professions like programming and device repair, but also for a host of softer skills like the basics of email etiquette.

Just as digital adaptation behind bars could help integrate inmates into the world’s digital future, it might also further a kind of self-directed, interactive, go-at-your-own-pace education needed in a place so ill-designed for learning.

As far back as the late 18th century, Quaker clergyman William Rogers began teaching inmates at Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail. As one of the earliest prison reformers, he conceived of education as a means for rehabilitating criminals. The idea was unthinkable to some. The jail’s warden was so worried about the possibility of educated prisoners rioting that he had a loaded cannon aimed at the site of Rogers’ first instructional meeting. Thankfully, he didn’t have to use it.

Today, prison administrators express similar fears (sans cannons) about connecting inmates to information, citing concerns that they will abuse access to the outside to harass victims or threaten witnesses, acquire contraband, or commit new crimes online. But as research shows that education is crucial in reducing recidivism, by 13 percentage points according to one 2014 evaluation, it’s long been worth the investment. The United States saves five dollars on re-imprisonment costs for every dollar spent on correctional education.

As the outside world becomes ever-dependent on digital skills and learning at pace with technology, conventional thinking around prison education isn’t working. “The current educational model is designed for failure,” says John Sonnenberg, the former director of e-learning for Illinois public schools, who is finalizing a dissertation about technology in prison education. [Full disclosure: Sonnenberg is currently employed by Pearson, a partner sponsor of this month’s series of stories.] While still in the research phase, he is advocating for a blended model of virtual learning systems and in-classroom teachers in prisons.

It’s well known that the United States has a prison problem. The country locks up more people per capita than anywhere on earth, incarcerating some 2.3 million inmates in 102 federal prisons, 1,719 state prisons, 942 juvenile correctional facilities, thousands of local jails, military prisons, and immigration detention centers. At only 41 percent, those incarcerated are twice as unlikely as the general population to have a high school education.

As for the current state of learning on the inside, Steven Hodas, who’s served as the executive director of the Office of Innovation at the New York City Department of Education and consulted for the Department of Justice (DOJ), knows all the pitfalls. “Remote locations make it hard, for example, to fully staff [prisons] with all of the instructors you would need if you were doing the face-to-face, old-school instructional model,” he says. That’s especially true considering the high proportion of inmates with special educational needs, and the widely varying quality of prison teachers.

Hodas highlights the frequency of security staff shortages, too: “If they’re short-handed one day “¦ they may not be able to move the inmates to the classrooms.” Lockdowns and punishments also keep inmates from going to class. And when there, widely varying education and motivation levels cause further disruption. Thus, the “time on task,” or time actually spent learning, is very low. “You need to increase the amount of learning time that takes place,” says Hodas. “And because of logistical and personnel problems, that’s pretty much impossible in an old-school learning model.” Fixed times, rigid locations, and set curricula simply aren’t a good fit for prisons.

If there is a history to the kind of technology-integrated education needed in the United States, it begins with people like Frank Martin–and it begins small. After nearly three decades of working with youth offenders in Oregon, Martin was supposed to retire last summer. After just one day off, he took up an encore career as a consultant on technology in educational corrections. Martin is convinced that “digital equity,” or bringing prisons into the 21st century with educational technology, is key to the future of prison education. “I want to have a school that is comparable to any school in the community,” he says of correctional facilities.

Starting in the 1990s, Martin set out to develop relationships with technology companies on behalf of the Oregon Youth Authority (OYA), which manages corrections for the state’s 12- to 24-year-olds. An early success involved a relationship with the nonprofit World Possible, which developed a server with preloaded content for offline communities. RACHEL (Remote Area Community Hotspot for Education and Learning), as the device is called, carries the tagline “the best of the web for people without internet” and offers access to educational resources like TED Talks, Wikipedia, and Radiolab.

Martin also built relationships with Intel, Google, and the startup Endless OS Computers to get free software and low-cost hardware. Many schools within OYA facilities have computer labs with Google devices and open-source educational apps.

Today, Martin and his Google partners are particularly excited about the potential of virtual reality to stimulate education. Virtual welding is already on offer at MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility, an all-male prison that houses offenders between the ages of 13 and 25 in northwest Oregon. Vocational instructor Ken Perine and his student Deven say that this system decreases the time it takes to achieve welding certificates by 30 percent.

OYA was also the first corrections agency to formalize student access to email and the internet for educational and employment-related purposes, Martin says. Students have carefully restricted and monitored access to the web for their studies, which is highly unusual in U.S. prisons. They can also take classes on coding or refurbishing broken devices.

While feedback is mostly anecdotal, administrators report reduced incident rates following the introduction of educational technology several years ago. It’s also common for the students to mention the computers before any other aspect of school.

Overall, the United States lags behind other countries in getting its prisoners learning. While New Zealand is aiming for nationwide access to preselected educational websites in its prisons, Belgium’s PrisonCloud system integrates administrative tasks with internet accessible within prison cells. Another unconventional initiative, taken up in Brazil and Italy, shaves days off an inmate’s sentence for each book he or she reads.

Meanwhile, in terms of vocational education, country performances are mixed. China, which has the world’s second largest prison population after the United States, has historically focused on labor rather than education in its correctional facilities. Vocational education is often tailored to local contexts, which means Canadian inmates learn to use chainsaws while Ethiopian inmates take tourism workshops.

When Hodas and the Vallas Group, the consultancy he worked with on the DOJ assignment, looked for a viable, more flexible and engaging educational experience compared to the one offered in U.S. prisons today, he wondered, “What kind of technology platform makes the most sense?” Ultimately, he concluded, “Tablets have the best risk/benefit scenario.”

America’s judicial system largely cuts off its detainees from accessing the internet and the host of educational resources it provides. As an antidote, companies like Edovo and JPay, a behemoth of private service provision to prisons, have distributed thousands of tablets loaded with educational and entertainment content but with security measures specifically designed for correctional facilities. Edovo is a social enterprise; its tablets, which have a Learn & Earn section with GED and college coursework, vocational videos, and ESL content, get signed out on loan to interested inmates who can log in with a specific username and password. The tablet’s programming is designed so that as a user completes educational or job-based material–digestible at any pace and at whatever skill level desired–he or she earns points toward certificates, as well as ones that unlock entertainment content such as movies and music in a Play & Spend section. Meanwhile, JPay’s tablets are part of the high-fees model that has made the prison service provider profitable: The JPay mini tablet has similar content, costs about $70, and is marketed to a prisoner’s family or friends to purchase–with recurring costs to send emails and videos back and forth as inmates plug in to connectivity kiosks under supervision.

Within prison education, the corporate presence can be murky. Since the private sector drives so much edtech innovation, there will always be a mix of private and public provision, says Hodas. Martin acknowledges the same, adding that in addition to corporate social responsibility, technology companies are also motivated by the desire to increase take-up of their products and collect data about usage.

While profit motives might get in the way of rehabilitation–and regulatory caution will be important to ensuring that educational outcomes aren’t sacrificed to these motives–government funding for prison education remains contentious. Despite the data about education’s positive influence on recidivism, taxpayers often prefer that their money not be spent on criminals. For instance, in response to a July 2016 OregonLive article about OYA’s receipt of a $1.1 million federal grant for college and career prep, some readers were up in arms about “rewarding” those who break the law with more resources.

OYA’s strategy has been to make the best use of the state and federal funds available, through building relationships with nonprofits, collecting donated equipment, and sharing resources within the correctional system and with school districts. OYA estimates that it spent approximately $80,000 in the last three years on Chromebooks, Chromeboxes, RACHEL servers, and related equipment. Joy Koenig, principal of Oak Creek’s Three Lakes High School, says, “We use technology with purpose. We are not the jet-setters for technology in the education world.”

The federal corrections system faces even more constraints than the state and county levels, for reasons including its massive scale, older inmates, and a complex funding structure that doesn’t necessarily reward good performance. Hodas points out that the DOJ spends significantly less per student on education than state prison systems do.

So how long would it take for a blended, online learning model to achieve significant take-up–say, with 25 percent of federal inmates meaningfully engaged with educational technology? According to Hodas, optimistically, a five-year scenario is possible.

Meanwhile, it’s state prisons that lock up a massive 1.35 million people, compared to those 211,000 in federal prisons, which makes Sonnenberg’s doctoral research particularly relevant. Preliminary numbers are encouraging; his data indicates that across Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice facilities, the number of graduates increased from 65 to 133 between 2013 and 2014 after a digital learning management system was brought in. (This was true even in spite of an overall drop in inmate population over that period.) Likewise, he says, the passing rate for the GED test was up from 46 percent in 2013 to 60 in 2015–numbers that are even more significant given the high school equivalency exam’s increase in difficulty since 2014.

Researchers agree that while prison education is clearly cost-effective, what we need now is stronger evidence about which forms of education are working. It would be unreasonable to see technology as a panacea, but in light of the intractable institutional problems and resource constraints of the U.S. prison system, it’s one of several avenues we should be exploring.

Just as there was when the Quaker William Rogers began educating prisoners in Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Jail, we can expect some fear and resistance to introducing digital resources into prisons. Thick walls and isolated locations alone challenge connectivity, and the low political appetite for risk means that the status quo is more attractive. But as 40 percent of those leaving American prisons will be re-incarcerated within three years, why not load the cautionary cannon and try something new.

How We Get To Next was a magazine that explored the future of science, technology, and culture from 2014 to 2019. This article is part of our How We Learn section, on the future of education. Click the logo to read more.